Some patients refuse to shower because it reminds them of the gas chambers. Others hoard meat in pillow cases because they fear going hungry.

At the Shaar Menashe Mental Health Center in northern Israel, it's as though the Holocaust never ended.

As Israel on Sunday night began its annual 24 hours of remembrance of the Nazi genocide, the focus is on the six million Jews murdered and on the survivors who built new lives in the Jewish state.

Separation anxiety, migraines and nightmares are only some of the main characteristics of these elderly people, most of whom suffer from some type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sometimes combined with disorders and other mental diseases.

But these are only the most difficult cases. Out of 230,000 Holocaust survivors living in Israel, more than one-tenth of them – about 25,000 people – are believed to be in need of mental aid and support.

The associations treating the Holocaust survivors say thousands of them do not receive the help they need. The public awareness has increased over the years, as has the State's investment in aid allowing them to live their last years in dignity. Ynet recently reported that survivors would be getting cheaper electricity and a significant reduction on medicine, but material needs are not everything.

Much less is ever said about the survivors for whom mental illness is part of the Holocaust's legacy.

At Shaar Menashe, patients remain frozen in time. Even today, 65 years after the end of World War II, there are sometimes screams of "The Nazis are coming!"

"These are the forgotten people. These are the ones who have been left behind, the people who have fallen between the cracks," said Rachel Tiram, the facility's longtime social worker.

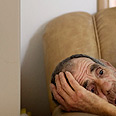

Shaar Menashe. Shadow of death camps never far away (Photo: AP)

Even among survivors with sanity intact, it can take decades to open up about their experiences. Here, most of the patients still won't speak. They are introverted and unresponsive. They mumble and shake uncontrollably, slump in front of blank TV screens and look aimlessly into the distance while sucking hard on cigarettes.

The details of their haunted pasts are sketchy and emerge only from hints in their behavior.

Meir Moskowitz, 81, endured pogroms and days inside a cramped cattle car in his native Romania. His body still quivers. During five hours in the company of visitors, he spoke just one word: "Germania."

Arieh Bleier, a gentle, 87-year-old Hungarian with deep, sullen eyes, survived the Mauthausen concentration camp. His parents and brother perished in Auschwitz. When asked about World War II, he looked away and shook his head.

For most of these survivors, reminiscing is impossible.

"It's hard to talk about it, very hard," said Devora Amiel, 78 and toothless, her speech slurred by a tongue puffed up from medication. She escaped a Polish ghetto, was taken in by a Christian family, and later grew up in an orphanage. She never found out what happened to her family.

"After you go through it, it's hard to tell," she said. "You can only scream about it."

Driven insane by experiences

Most survivors in Israel went on to live productive lives, and their ranks include politicians, authors and Nobel Prize laureates. But for decades after becoming a state, Israel tended to look for role models among the fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising rather than Jews meekly filing into cattle cars and gas chambers.

Survivors driven insane by their experiences ended up in ordinary institutions which were not always a good fit; for instance, they had to wear pajamas, which reminded them of concentration camp inmates' uniforms. Sometimes the children and grandchildren of patients were simply told they had died in the Holocaust.

Few of them are still with us today, "both because the survivors' population has grown old, and because the life expectancy of patients in mental institutions is lower than that of the entire population," explains Dr. Yehuda Baruch, director of the Abarbanel Mental Health Center. "The last time I checked, there were six such patients in the entire country."

Only in 1998 did Israel build three homes for survivors, starting with Shaar Menashe.

Today about 220,000 survivors are still alive in Israel. About 200 are in Shaar Menashe and the other two homes.

Some have lived in mental institutions since their liberation, while others developed mental illness late in life.

Today, most mentally ill Holocaust survivors have managed to function throughout the years, but their mental condition worsened over time. They include elderly people who have developed dementia, depression and other mental problems, which brought back the memory of the Holocaust and turned it into the disorder's main axis.

Only in 1998 did Israel build three homes for survivors - Shaar Menashe, Beer Yaakov and Lev Hasharon – where some of the most difficult cases are treated, those who have no supporting family to care for them.

Shlomi Ezer, a clinical social worker at the Beer Yaakov hostel, which is run by the Association for Public Health, explains that most of the patients at his hostel are Holocaust survivors who spent many years in private institutions. Others are survivors who were hospitalized in psychiatric hospitals and ended up in the hostel.

"This place functions like a nursing home for exhausted people with cognitive and functional limitations, who cannot live among the community. One-third of our patients are childless and view this place as an alternative home, a family model they don't have in real life. It's not a hospitalization and we don't refer to our patients as sick people. They are tenants. There are no pajamas or symbols, and on Fridays there is homemade food."

In need of significant aid and support

Alexander Grinshpoon, director of Shaar Menashe, said all survivors have some form of post-traumatic stress disorder. But the roughly 80 in his care are men and women who could not overcome their wartime traumas, perhaps because their suffering was so profound, or because they were predisposed to mental illness - or maybe because their minds simply crashed under the weight of their experiences.

Grinshpoon said research has shown that those who have experienced emotional trauma are five times more likely to develop serious mental illnesses. Holocaust survivors, he said, have a higher rate of suicide.

Eighty percent have trouble sleeping and two-thirds suffer from emotional distress, according to a survey commissioned by the Foundation for the Benefit of Holocaust Victims in Israel.

The foundation's chairman, Zeev Factor, is an Auschwitz survivor. He says he has been able to maintain his sanity by focusing on the present but still suffers in his dreams. "I sometimes wake up from them covered in sweat from head to toe," he said.

'They live in this world and in that world at the same time' (Photo: AP)

"The Holocaust survivors living in Israel today are increasingly in need of significant aid and support, in order to live the years they have left in dignity," Factor says. "It's true that following a persistent battle, the injustice which lasted years has been amended and there are no homeless or starving Holocaust survivors, but a person cannot live on bread alone.

"Unfortunately, many Holocaust survivors suffer from emotional distress, depression, loneliness and chronic health problems, and the Israeli society has the moral duty to care for all their needs over the last years of their lives."

It's not uncommon for mental patients anywhere to believe the world is coming to an end. But for these patients whose world really did come apart, paranoia is well-founded.

Tiram, the social worker, spoke of an elderly woman in Shaar Menashe who constantly fears the police are coming for her.

"This is something that really happened to her. It's not something that she is making up," Tiram said. "Each time they go to sleep, they go back to the Holocaust, to reliving their childhood."

Grinshpoon said most patients have trouble distinguishing between fantasy and reality, and their stories are often unreliable. One man says he was a fighter pilot during World War II, another says he's a ninja. A third is convinced he's an Arab and says he hates Jews. One thinks she is still in Europe and is shocked to see an elderly woman in the mirror.

At Shaar Menashe, patients are not required to wear pajamas. They have lawns, arts and crafts lessons and workshops with pets. Some have developed hobbies, cultivated friendships and even reconnected with children and grandchildren. Many of the volunteers working here are survivors themselves.

Still, the shadow of death camps, crematoria, deportations and gas chambers is never far away.

Said Factor, of the benefit foundation: "They live in this world and in that world at the same time."

Yael Branovksy and Meital Yasur-Beit Or contributed to this report