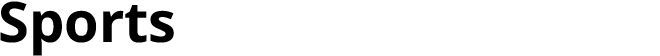

With the World Cup in faraway Brazil coming at a time of unprecedented sectarian violence and soaring tension in the Middle East, some Arab football fans have been reduced to watching matches in secret or even - and this is where it gets complicated - on a TV channel owned by Israel.

Since the World Cup kicked off three weeks ago, Sunni Muslim extremists have seized territory in Iraq and Syria and declared an Islamic state. Lebanon has been hit by a spate of suicide bombings. Israelis and Palestinians were pushed to full conflict after the murders of four teenagers. Egypt's political divide grew wider as hundreds of people charged with supporting the ousted Muslim Brotherhood group were convicted of terrorism-related crimes - including three journalists for Qatar-owned Al-Jazeera network.

Many accuse the Doha-based network of editorial bias in favor of the now banned Islamic group in Egypt and of Sunni insurgents fighting Shiite-dominated governments in Syria and Iraq.

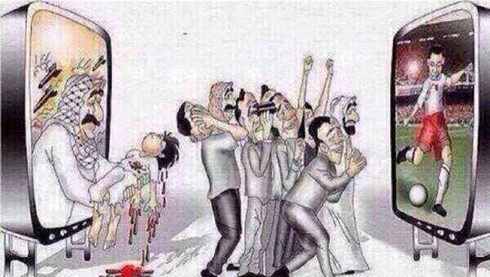

Qatar's media conglomerate owns broadcasting rights to the World Cup in the Middle East, charging viewers from $110 to $320 for a three-month subscription that includes the 64 World Cup matches -- a tournament that should have been a welcome escape for millions of football fans.

Most fans can't afford to pay for the satellite broadcasts of the World Cup, which was previously shown around the region on state free-to-air channels. Some Egyptians refuse to subscribe to Qatar's channel for political reasons.

Watching a recent match in a cafe in downtown Cairo, 21-year-old student Mohammed Mostafa said his family is boycotting Al-Jazeera and instead tunes in to an Israeli channel that has been broadcasting the World Cup for free, with commentary in Hebrew -- a foreign language to most Arabs.

"My parents refuse to give money to the Brotherhood," Mostafa explained.

That kind of attitude has outraged officials in Egypt, where state media has lashed out at Israel by saying it has opportunistically barged into the Arab broadcasting market.

"Israeli media penetration into the Arab community is more devastating than its missiles," said Mohammed Shabana, the director of Egypt's Sports Writers Association. But he also criticized Qatar, saying the oil-rich Gulf state should have dismantled Israel's plot to win over Egyptian fans, and offered a subsidized deal to the Cairo government that would air the World Cup to its citizens for free.

Israel "is our biggest enemy," Shabana said. "If the only way (to avoid Israel's channel) is to give money to Qatar, then we should do it."

For Raaouf Sobhy, a cafe owner in Cairo's upscale Heliopolis district, choosing which channel to watch was a simple decision.

"I hate Qatar more than Israel," Sobhy said. "I don't think Israel is harming us as much as Qatar."

In south Lebanon near the frontier with Israel, some turn on the Israeli broadcast, even though Israeli TV channels have been banned since 2000 when Israel withdrew its troops following 18 years of occupation. Israel's arch enemy, the Shiite militant group Hezbollah, dominates south Lebanon and its fighters have fought on the Syrian government side. Qatar is not popular there, though, because of its support for Sunni rebels in Syria.

In the village of Ein Ibil, a man watching the Israeli channel with Hebrew - a language he does not understand - commentary blasting away said he neither cares about the ban nor the country broadcasting it to him.

"I just want to watch the game," he said on condition of anonymity for fear of harassment. "You don't need subtitles to watch football."

Israel welcomed viewers in neighboring countries, saying it was part of the Jewish state's diplomatic outreach to the Arab World.

Ofir Gendelman, a spokesman for the Arabic Media in the Israeli Prime Minister's office, posted on his official Facebook page a dictionary of Hebrew soccer terms translated into Arabic.

"Reactions were mixed, but a lot of people appreciated the gesture," Gendelman said. "I do find it fascinating that millions of Arab viewers are now watching the World Cup on Israeli TV while learning soccer terminology in Hebrew."

Few would dare tune into an Israeli channel in Syria, where Israel remains the primary enemy despite a raging civil war which pits predominantly Sunni Muslim rebels against the forces of President Bashar Assad, who belongs to a sect in Shiite Islam. As residents of the capital enjoyed a temporary lull in mortar attacks during the World Cup, fans seem to ignore the fact that Qatar - a country on top of Assad's black list for supporting the opposition - owns the tournament broadcasting rights that were obtained in Syria by two private companies.

There has been no World Cup viewing in public in Raqqa, a city in eastern Syria under control of a Sunni extremist group that considers most TV stations to be heretic, an opposition activist, who goes by the name Abu Ali, said in an interview over Skype. At home, the activist said, some have watched World Cup matches on a Turkish channel.

In the Iraqi capital Baghdad, fans have shunned cafes as a World Cup viewing option. Cafes have become favorite targets for Sunni extremists of the armed group that has declared an Islamic state in northern Iraq and in eastern Syria as it advances to Baghdad, the seat of the Shiite-dominated government.

Back in the West Bank, Palestinians flipped onto Hebrew-language channels to watch the World Cup, despite escalating violence in Gaza.

Hudaifa Srour, who lives in the West Bank village of Naalin, said most people don't care what language the commentators are speaking.

"Our people are eager to escape the political problems, so even those who are not interested in sports, watch the World Cup," Srour said.