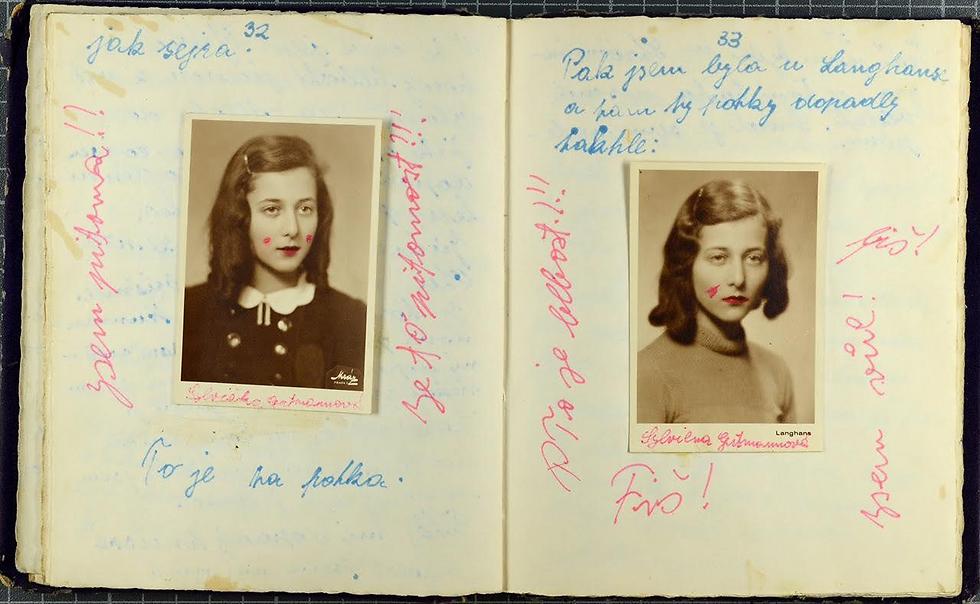

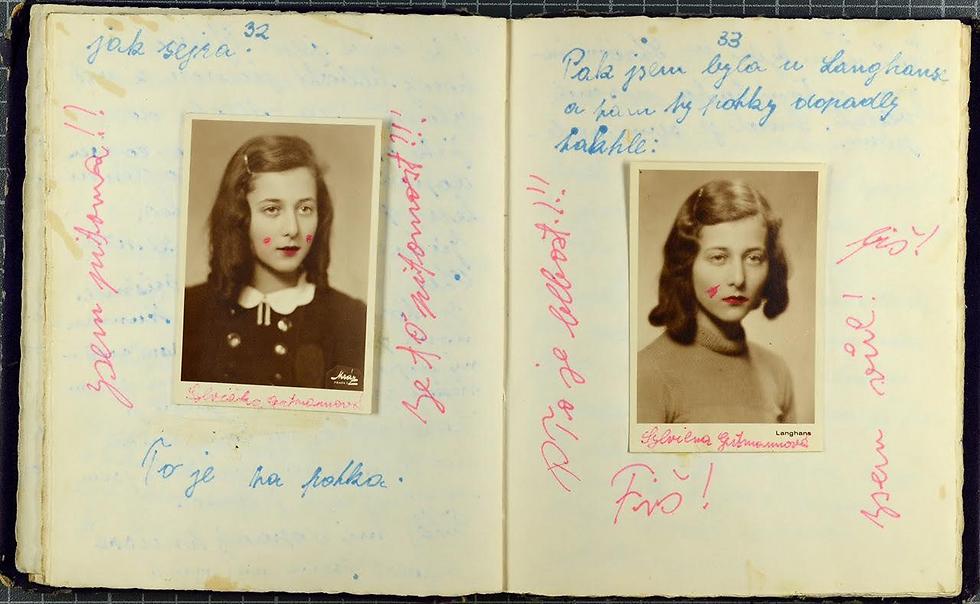

‘We’ll be labeled as Jews soon, and I’m quite curious about it’

In a 1941-1942 diary, a young Czech girl named Sylvia Gotmanova discussed love, her friends and her looks, mentioning the difficult events taking place around her between the lines. ‘Many people are being transported to Poland, and it will reach us too,’ she wrote just a few months before being sent to the Sobibor extermination camp, where she was murdered with her family.

Sylvia wrote the diary from 1941 to 1942 and dedicated most of it to the world of a growing young girl, the boys she fell in love with, her looks, and the time she spent with her friends. The dramatic events of the war and the Holocaust—as they were experienced by Sylvia, her family and the people she knew—can only be discovered between the lines.

The first lines in her diary were written on September 11, 1941: “Yesterday was a wonderful day. First of all, I came home from the hospital, where I lay in bed for six weeks due to a fall. Second, I received this diary. Third, my father gave me 100 korunas for a bicycle. I already have 700 korunas and I hope we will buy the bike soon."

“Before the fall,” she goes on, “I rode my cousin Yeray’s bike and now I can’t because I can barely walk, and then I’m not allowed to meet with other children for 14 more days. It’s so stupid. I’m not allowed to go to school… I’m not allowed to sit in the kitchen, because that’s where Yeray, Peter and Edita are. We are living in a place rented from Uncle Aula, who I was terribly afraid of.”

That same day she also writes: “It’s raining today, so I can’t go out. So it really was a genius idea by grandmother to buy me a diary, especially one with a key. My sister keeps a diary, but in a notebook, and she locks it in a safe.”

On September 16, for the first time, she casually mentions the labeling of Jews: “When I was at the hospital, I got a letter from Honse Lieven. A year ago, I would have probably been overjoyed, but this year I don’t really care. Both Eva and Greta are already seeing someone. I’m the only one who isn’t. We’re supposed to be labeled as Jews soon. I’m quite curious about it.” A week later she notes, “We have been labeled for a while now, and it’s not that bad.”

Immediately afterwards, she writes about her personal life again: “I’m in love—should I write it? With Peter Herzog, a friend of Peter Mahror, but it's hopeless, because he has a girlfriend. It doesn’t bother me, of course, as long as I can talk to him. I think he’s in love with me because another friend, Karel, asked me how old I was. Peter Herzog told me he was offended that I didn’t say hi to him. And I don’t care. I want Peter.”

'Terribly unlucky in love'

A month later, Sylvia writes: “A lot has changed since the last time I wrote in the diary. We have been wearing badges indicating that we are Jews, sort of yellow stars (this sentence was erased). Many people are being transported to Poland now, and it will reach us too.”

Later, she writes that she is no longer in love with Peter Herzog, but with a different Peter—her cousin. “I am already ashamed to write in my diary such nonsense,” she adds.

In November, she describes the following situation: “Yesterday, as I was walking home, on Malanje Street, elderly women were selling lemons, which are usually not for sale. I saw a Jew with a beard stop a few steps before one of the elderly women with the lemons. He stood there for a couple of moments and looked at her. Then he suddenly moved and got closer, but then he immediately changed his mind, looked down at his watch and walked away with a sad expression on his face, so I broke into tears on the spot. I thought that he may have a sick child at home, who can’t be without lemon, and now he can’t buy the lemons.”

In December 1941, Sylvia describes the difficult sights of Jews being transported to the camps: “I haven’t written in my diary for a long time. I am very lazy and forgetful. A lot has changed in the meantime. The transports to Poland are continuing, and now it’s to Terezin. Zoza’s guy, Badia, has gone and she was crying all the time even before he left. Edith Mahrer, her mother and father and grandmother (who gave me the diary) and grandfather will leave tomorrow. And Edith Morgenstern. I’m completely shocked.”

The last time Sylvia wrote in her diary was on April 13, 1942, a week after her 13th birthday. “There’s no news. School has begun. It’s disgusting. There’s a test tomorrow. I couldn’t care less. I’ll get a low grade, so what, nothing will happen. There are transports again. This is a horrible, hopeless situation.”

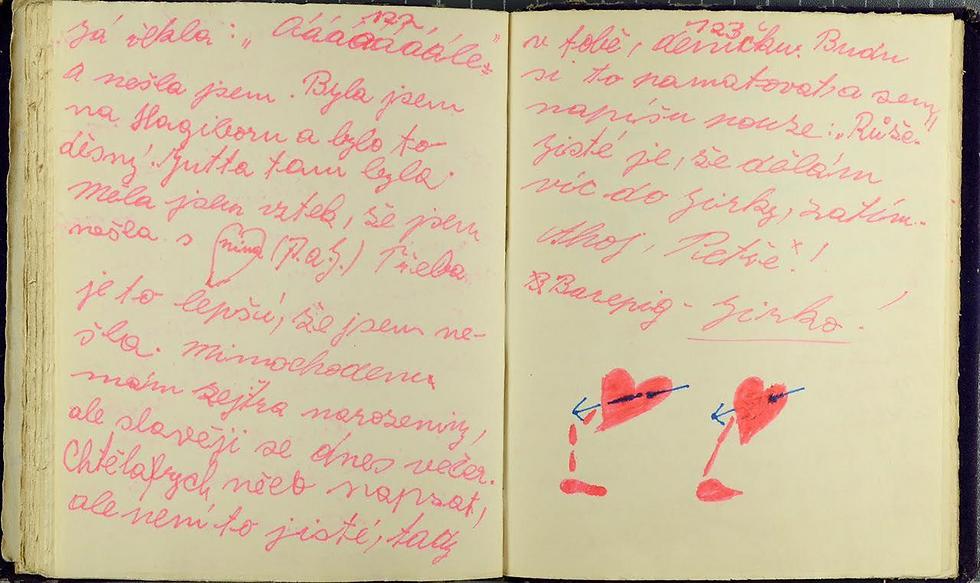

Sylvia keeps writing about her love for her cousin Peter: “I am very much in love with Peter, and at the same time I am jealous of Zoza and Lea. I have known for a long time that Peter is in love with Lea, but today Zoza told me that it’s mutual. I am terribly unlucky.”

The young girl concludes her diary with the following words: “I’d like to stop being occupied with Peter, but it’s not working. Well, goodbye.”

Less than a month later, on May 7, 1942, Sylvia and her family—her parents Simon and Stefanka and her sister Zuzana—were sent to the Theresienstadt ghetto. After about a month in the ghetto, they were sent to the Sobibor extermination camp, where they were murdered.

The diary was donated to the Ghetto Fighters’ House museum in the Western Galilee by a Swedish woman, whose mother was Zuzana’s classmate.

Anat Breitman, who is in charge of the archive at the Ghetto Fighters’ House museum, defines the diary as an emotionally moving document. “It mostly demonstrates how the girl tries to maintain the old order, to keep up with her routine social life on the backdrop of the difficult events taking place around her, which barely infiltrate the world she is describing.”

The Ghetto Fighters’ House museum collected the details about Sylvia and her fate from the donor’s stories and from information found at Yad Vashem, and is asking anyone who has any other information about the young girl and her family to contact the museum.