Ruth as a model for modern conversions

Opinion: Most rabbis follow the stringent approach mandating that converts accept all religious obligations, but very few are tempted; if we are to end the marginalization of so many FSU immigrants and save conversion from irrelevancy, we ought to consider the more lenient approach

The most prominent feature of Israel's character as the Jewish nation-state is the Law of Return, which allows entry into Israel not only for Jews but also for non-Jews who have familial ties with Jews.

As a result, of the more than one million immigrants who arrived in Israel from the former Soviet Union, about a third (350,000) of whom are not Jewish but have Jewish family members. This group grew by about 10,000 people annually, as a result of natural increase and continued immigration. Their classification by the state as non-Jews raises some serious problems.

Their human rights are violated by the fact that they cannot marry a Jew in Israel. On a national level, their exclusion from the Jewish collective may weaken their identification with the state and may bring about further tribal fragmentation of Israeli society.

From a religious perspective, because they cannot Halachically marry other Jews, some elements are calling for the implementation of a central lineage database that will differentiate between Jews and non-Jews. Formalizing the situation might drive a historic wedge through the heart of the Jewish people with unforeseen consequences for the future of the State of Israel.

Seemingly, the solution is clear: Judaism allows others to join through conversion, but the data shows that only about 7% of non-Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe to Israel undergo conversion.

The conversion track is unattractive to many because it requires converts to become religious as a condition for the process. Many potential converts are not willing to live by the strict guidelines of Orthodox Judaism that even most Jews find to demanding to commit to. The result is that in order to convert, they must pretend. The path to Judaism is paved with deception and for that reason many turn their backs. But can this trend be turned around?

We must first ask ourselves, what exactly is conversion? Is it about joining a religion or a nation? If it is joining a religion, then it is only natural that converts be asked to commit to keeping the rules of the Torah in order to become a Jew. That was the opinion of the 10th century Jewish sage Saadia Gaon who ruled that "our nation is nothing without the Torah." Religion is the central tenet that forms our national identity.

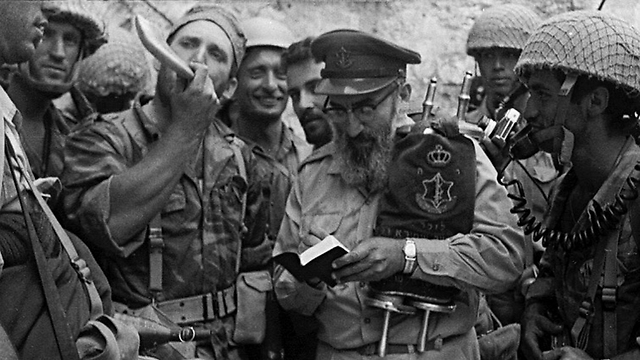

On the other hand, there is a Halachic tradition that Judaism is a "nation" and only after a person joins do they become obligated to follow all of the rules. This is referenced in the biblical book of Ruth the convert, the ancestor of King David and the Jewish Messiah: "Your nation is my nation and your God my God." Meaning, first join the nation and only afterwards, as a result of joining, does the religious obligation become relevant.

This dispute is alive and well today. The Haredim and most of the religious-Zionist rabbis hold by the more stringent definition, which makes it difficult to implement the conversion potential in Israel. In contrast, there are several prominent rabbis, including three former chief rabbis: Eliyahu Bakshi-Doron, Shlomo Goren and Ben Zion Uziel, who argue that conversion means joining the nation and that adherence to the commandments of the Torah is not a condition for conversion to Judaism. The national conversions court ought to consider this lenient position.

In addition to the factors listed above, the Rabbinate ought to recognize that a strict conversions policy makes the issue of conversion irrelevant. The massive influx of "non-Jewish Jews" in Israeli society grants legitimacy for the sociological, non-religious membership of Judaism, thereby making conversion superfluous. Some will welcome this development, but it must be understood that this will be a real revolution in the history of the Jewish people (at least since the days of Ezra and Nehemiah, 2,500 years ago); it is difficult to comprehend the significance and danger of this.

And in conclusion, the demographic aspect: most Diaspora Jews choose to marry non-Jews. Is it right to eliminate these families from the Jewish nation even if the non-Jewish spouse is interested in joining Judaism? Is it right to allow for one generation of Jews, the current one, to cut off significant portions of the Jewish people for eternity?

A Halachic conversions policy must deal with the question of whether the current Jewish collective is interested in becoming more open or more closed.

Yedidya Stern is a senior fellow at the Israeli Institute for Democracy and a professor of law at Bar-Ilan University.