The Six Day War - May 1967, one moment before

There was tension on the northern border, and the southern border wasn’t calm. The Defense Minister had little military experience. The nations of the world were boycotting the Independence Day march in Jerusalem. The Asian UN Secretary General came to the region to try to mediate between Israel and the Arab countries but returned to New York empty-handed. One of the Arab leaders was making belligerent declarations, and the Palestinians were threatening terrorist attacks against Israel. This isn’t about the past month, but about the events preceding the Six Day War forty years ago

Israel, which one month earlier had downed six Syrian MiG-21s in a battle for the Golan Heights water sources, sent a clear message to Syria through Prime Minister Levi Eshkol’s statement that Syria was primarily responsible for the sabotage, though Lebanon also was partly responsible. Israel, attempting to use diplomacy to ease the tension on the northern border, approached UN Security Council members with a clear message: Israel cannot accept Syria’s provocations and the wave of terrorist attacks. Foreign Minister Abba Eban also warned Damascus that the Syrian assumption that Israel would not respond was groundless.

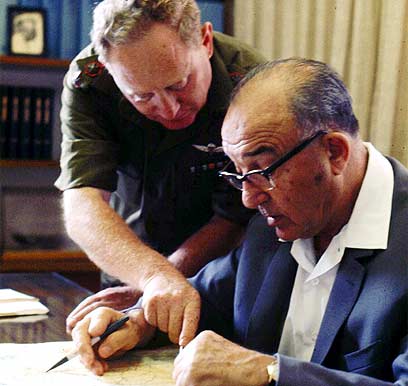

Levi Eshkol in his office. A message to Syria.

(Photo: David Rubinger)

Syria, suffering from domestic problems and demonstrations by religious leaders against the ruling Ba’ath Party, took Israel’s threats seriously. Syrian UN representative George Tomeh called for an urgent meeting of the Security Council to discuss the Israeli threats. Damascus, refusing to content itself with diplomatic activity, attempted to mobilize Egyptian support. UN Secretary General U Thant condemned the actions against Israel, but would not say that Syria was responsible for the region’s deteriorating security situation.

Mimouna celebrations and religious protests

In the first half of May, life in Israel went on as usual. In Jerusalem’s Sanhedrin Park, Israelis of North African descent celebrated a holiday that was then called “Alfassi Mimouna,” but the hundreds of revelers returned home because of the strong rains. Eshkol took time off from the burning affairs of state to host an Israeli youth team that had won an international tournament in Bangkok.

And what was happening in the Knesset? Even then there were calls to change the electoral system to a regional one. Minister Moshe Kol, leader of the Independent Liberals, recommended dividing the country into 12 electoral districts, with each district choosing 10 Knesset members. At the request of Gahal Party MK Yosef Sapir, a special recess meeting of the Knesset was called to discuss the findings of the annual State Comptroller’s Report.

Another topic discussed in the Knesset, at the request of Rafi Party MK Yosef Almog, was the sale of the Shalom ocean liner to Germany. Eshkol’s wide coalition managed to remove both items from the agenda because there were Knesset committees dealing with the issues, and MK Sapir was angry. Former Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion attacked his successor in the Rafi Party journal New Look. “Some of Eshkol’s pupils are people I knew as honest and precious until they learned the doctrine of falsehood from their new leader,” wrote Israel’s first premier.

Tel Avivians had a problem. Even then there was a lack of parking, and in 1967 thugs took control of parking lots, forcing drivers to allow them to wash their cars for a fee. Tel Aviv’s city government promised to fight back, and city parking inspectors were sent to protect the drivers, who didn’t want their cars washed every day. Things were also stormy in neighboring Ramat Gan. The coalition of Mayor Avraham Krinitzy, who had served more than four decades in the position, was shaky. But not to worry: within a few days he brought in a new city council member and the city once again became calm and stable. In other parts of the world, people talked about a man landing on the moon by 1970.

And what was new with the religious? Things were far from quiet on that front. The problem of autopsies was once again in the headlines, with the haredim claiming that organs were removed from the body of a rabbi who had died in Bnei Brak. The family of a patient who had died in Hadera’s Hillel Yaffee Hospital, told that an autopsy was needed to discover the cause of death, attacked hospital staff. National religious and haredi demonstrators protested against the autopsies, and the demonstrations spread to the United States within a few days. The National Religious Party, a regular member of the coalition, demanded clarifications from the Prime Minister.

The religious were also fighting to prevent the staging of Yaakov Orland’s play “This City”, angry because, they claimed, the play depicted religious Jews who were intending to wave the white flag during the siege of Jerusalem in 1948. To prevent the play from being staged an appeal to the High Court of Justice was also considered, the claim being that staging it would harm public order.

In honor of its 19th Independence Day, Israel decided to hold a military parade in Jerusalem, which was divided between Jordan and Israel. It invited ambassadors from foreign countries, but though the city was still divided, even representatives of Israel’s greatest friends at that time, the US, France, Britain, and West Germany, announced that they would not attend the parade. The US State Department explained the dilemma, stating that the US ambassador’s attendance at a military parade in Jerusalem would offend Jordan, but his failure to attend would offend Israel.

In the end, Washington, Paris, London, and Bonn decided not to attend, with all of them stating that this would not affect their close relations with Israel. Soldiers from the Jordanian Legion, permanently stationed in east Jerusalem, did watch the parade. Watching the Israeli army they enjoyed the military marches playing in the background, never thinking that within less than a month, the rifle barrels and weaponry displayed in the parade would be turned against them.

Egypt goes from threats to actions

In the first half of May, Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser threatened Israel more than once and called Jordan’s King Hussein an agent of American and Israeli intelligence.

Arab representatives met in Alexandria. PLO Chairman Ahmad Shukairy issued a call to step up terrorism against Israel, and also appealed to the Arab countries not to place obstacles in the path of the terrorists attacking Israel, and even to support them. Shukairy blamed Jordan for the deaths of 20 men from five Palestinian organizations who were killed in incidents with IDF forces. The next terrorist attack came soon after that when terrorists infiltrated Moshav Amatzia in the Lachish District and blew up a house and telephone pole. Luckily, the house was abandoned.

In the second half of May the Egyptian army entered the Sinai. Nasser’s deputy, Field Marshall Abdel Hakim Amer, personally oversaw the deployment of the army, which was supposed to reach the Israeli border within several days. The UN observer force, which arrived in the Sinai and the Gaza Strip after Israel evacuated the territories it had conquered in the 1956 Sinai Campaign, was supposed to separate Israel from Egyptian army forces. Prime Minister Eshkol - who was also serving as Defense Minister, though the sum total of his military experience was service in the Jewish Legion - held a security assessment in his office. Sources in Jerusalem stated after the meeting that they did not believe war was imminent.

But May 17 saw an alarming development, with the Egyptian army demanding that UN inspectors leave the Sinai and Gaza Strip. Egypt’s Chief of Staff announced that he had declared a state of preparedness for war against Israel. In a letter sent to the UN by the commander of Egyptian forces, he explained that “I have given orders to my army to be ready for a war against Israel in the event of Israeli aggression against Syria or any other Arab country. I demand the immediate evacuation of UN forces from the border in order to ensure the safety of the international organization’s men.” The UN force, by the way, numbered 4,000 soldiers.

Israel - which until that day had believed that Egypt, immersed in a civil war in Yemen, would not open a second front - followed the situation anxiously. Yedioth Ahronot’s May 18 headline read as follows: “IDF: We’ve taken appropriate steps in light of Egypt’s reinforcements in the Sinai.” Political officials in Jerusalem acknowledged that “a military deterioration is possible.” The UN, smelling the winds of approaching war, decided to send a high-ranking official to mediate between the sides.

U Thant was chosen for the mission, and departed for Cairo. Even before his departure he capitulated, stating that without Egypt’s agreement it would be impossible to leave the UN force in place. In a last-minute effort, Abba Eban declared that a unilateral withdrawal from Gaza was incompatible with UN assurances. Commentators around the world asserted that Egypt was flexing its muscles, and few people spoke of war.

The evacuation of UN soldiers from Sinai and the Gaza Strip took place several days later, and Jerusalem, anticipating Egypt’s next step, threatened that a challenge to Israel’s freedom of navigation in the Red Sea would constitute a casus belli. Nevertheless, military commentators believed that the balance of forces was actually in Israel’s favor because Egypt could not fight on two fronts, in Yemen and in the Sinai.

The president leaves and returns, the tension grows

The institution of the presidency was greatly respected at that time. When the president went abroad, top government officials - the prime minister, ministers, MKs, and security and police officials - accompanied him to the airport. That’s how it was in May when President Zalman Shazar left for a 17-day visit to Canada, Iceland, and Scotland: all the country’s high-ranking officials came to honor Israel’s third president, and Mirage jets flew overhead. In the end, because of the tension, Shazar was forced to cut short his visit abroad. When he returned to the airport at Lod after a little more than a week, few people were there to receive him. The vast majority of the Israeli leadership was busy with the security situation.

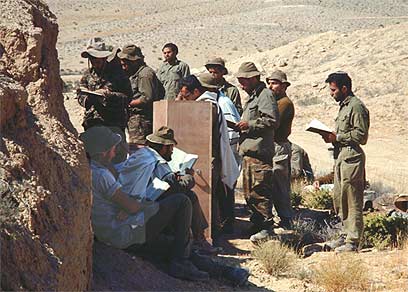

Keeping in touch with home

(Michah Hen, GPO)

Syria was preparing for war. Damascus and Prague signed a weapons agreement providing Syria with cannons, anti-aircraft missiles, mortars, and tanks. At the same time, Syria was attempting to purchase additional MiG-21s from the Soviet Union. Egypt and Syria took actions without updating or consulting with the Arab League. Egypt reinforced its forces in the Sinai, and three Palestinian brigades joined them. East Germany announced it would supply weapons to the PLO, and Cairo said for the first time that it supported terrorist actions by Palestinians against Israel.

Israel was worried that Egyptian forces in the Sinai were larger than before the 1956 Sinai Campaign. The commander of these forces tried to allay the fears a bit, stating that “we will fight only if Israel attacks.” The US tried to involve the Soviet Union and to get it to use its influence with Cairo. Western European countries were angry with the UN secretary general for ordering his forces to capitulate quickly in the Sinai, while in Eastern Europe Israel was blamed for the deteriorating situation.

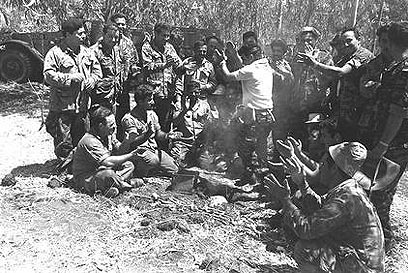

We’ve reported for reserve duty

Nasser declared that his forces were withdrawing from Yemen and making their way to Sinai, and the IDF had a general call-up of forces. Israel’s economy was nearly totally paralyzed, all fit men having been drafted. Egypt’s al-Ahram reported that Israel was continuing to send forces toward the border with Sinai. On the other side of the border, an Egyptian military force seized Sharm e-Sheikh. Lebanon also rushed reinforcements to the border with Israel, fearing a military flare-up.

(Photo: David Rubinger)

Yedioth Ahronot decided to help the mobilized soldiers to stay in touch with their worried families at home. “Regards to the draftees” from the soldiers’ families took up several pages in the paper, which also featured a section with “Regards to home” from the soldiers. Military correspondents gave situation assessments of the forces, which were kept almost unoccupied as war drew closer. In the meantime, Israelis were reporting to Israeli embassies in western Europe and the United States, seeking to get home to report for reserve duty.

In the kingdom to the east it was business as usual: tourists crossing at the Mandelbaum Gate from the Jordanian to the Israeli part of Jerusalem reported that they had not felt any tension in Jordan. However, they did report lively military traffic of Jordanian Legion forces from Amman in the direction of Judea and Samaria.

Nasser closes the Straits of Tiran

The situation was escalated further when Egypt’s president closed the Straits of Tiran and firmly declared that “no Israeli ship will pass. We will also prevent strategic materials from being brought to Israel by non-Israeli ships. If Israel’s leaders and General Rabin want war, our forces are waiting for them. For this purpose our forces are now in Sharm e-Sheikh. The waters of the Straits of Tiran are ours.” Moscow supported Cairo’s moves, while the US warned Israel and Egypt not to take military action.

In a speech to the Knesset, Eshkol tried to calm the situation. “I want to say to the Arab states, including Egypt and Syria, that we do not seek war, that we do not want to attack. We’ve said this many times: We have no intention to harm the security, the territory, or the rights of those states. Since 1965 there have been 113 actions and attempts to lay mines and commit sabotage for which Syria is responsible. Since 1966 we have protested this activity to the UN in 34 letters.” Despite the premier's conciliatory message, Israel continued to prepare for war.

(Photo: Arye Kanfer, GPO)

For Egypt, the next stage was laying mines in the Strait of Tiran. Eban made an urgent visit to the US to meet with President Lyndon Johnson and other senior Administration officials and receive their support in the event of war. Cairo won the full support of Moscow, which announced that it would come to the Arab states’ defense in the event of war. The Security Council, worried by the latest developments in the Middle East, convened an emergency session, where the American ambassador read sections of Alice in Wonderland and the Russian ambassador talked about monkeys falling from trees while praising the peace-loving Arabs. The emergency session, like others before and after, ended without results.

In Jerusalem calls were growing for a national unity government, while the National Religious Party called for an emergency government. Ben-Gurion and Herut Party leader Menachem Begin, who were not on good terms, met in Sde Boker. Begin called upon Ben-Gurion to join the Eshkol government and contribute his experience, but the former prime minister refused. Mapai, the party in power, initially refused the proposal to widen the government, but changed its mind within a few days.

Several days later, in an interview with Yedioth Ahronot, Begin told how he had tried to persuade Eshkol to appoint Ben-Gurion prime minister in his place. “I asked Shimon Peres,” said Begin, “could Ben-Gurion, at his age, take upon himself the affairs of state? Would he be prepared to do that as the prime minister in a national unity government? Within a few days Peres responded in the affirmative. In consultation with members of Rafi and Gahal I was given the task of approaching Eshkol.”

At the same time, Israeli diplomatic efforts around the world were continuing. Eban went to the United States to mobilize support. Eban, one of Israel’s most senior diplomats, refused to give up, meeting three times in one day with Secretary of State Dean Rusk. But the attempts to bring the US onto Israel’s side failed, with Washington announcing that the US would intervene only if the USSR joined the fighting. President Johnson asked Israel not to start a military operation, and promised to supply oil and military equipment. In contrast, the West German Finance Minister was sorry that he could not provide Israel with weapons.

On May 28, a week before war broke out, Eshkol made a radio address to the nation that many people remember because the prime minister became confused and appeared hesitant. Eshkol and his advisors changed the text of the speech a number of times, and during the live broadcast he read a sentence that had been changed at the last moment from “withdrawing forces” to “moving forces.” In this section Eshkol apparently could not read the change, and when he started to stammer in front of the live microphone, the entire country heard him. A short time later lessons were learned and it was Major-General (res) Chaim Herzog, later Israel’s sixth president, who went on the air, becoming Israel Radio's commentator on the tension, and later on the war.

Life on the home front

In late May 1967, newspapers reported that life in Tel Aviv was going on almost as usual. While the number of men around was smaller than usual because many had been called up, the cafes and places of entertainment were not empty. Although the assessment was that chances were small that Tel Aviv would be hit in a war, shelters were made ready and volunteers were trained for an emergency. Ten thousand high school students dug trenches filled with sandbags, distributed informational material, helped deliver mail, and helped out in hospitals.

Jerusalem, which was closer to the front, also prepared for war. Those living in haredi neighborhoods filled sandbags to protect themselves against bullets from the Jordanian enemy. In the south, on the other hand, soldiers awaiting orders from above were received with candies. A son was born to one of the soldiers, and since he couldn't get home to hold a brit, the baby and mohel were brought to the front, where the ceremony was conducted between a tank and an armored personnel carrier.

(Photo: David Rubinger)

Huge posters asked the citizenry to purchase bonds to help the war effort. A special security tax was levied, and the public was asked to purchase a “security loan.” The Chief Rabbinate declared a day of fasting and prayer for June 1 - perhaps help would come from Heaven. Those who had not been called up were sent to work in essential places, and public transport nearly came to a halt because many drivers and buses had been called up.

Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin asked the soldiers who’d been called up for “a bit of patience.” Eshkol explained in the Knesset why Israel was waiting: “We expect the countries that support the principle of freedom of navigation to take effective action to open the Straits and the Gulf.” Ben-Gurion stated: “His behavior and our leaders will determine our fate.” And only Abie Nathan thought of peace, declaring his intention to fly to Cairo to meet with senior Egyptian officials.

Yitzhak Rabin and Levi Eshkol tour the Negev

(Photo: GPO)

The Arabs were not waiting. Jordan and Syria, two countries with chilly relations during this period, decided to cooperate. Iraq also announced that it would come to the aid of Syria and Egypt. Russia sent Syria advanced MiG-23 jets. Egypt airlifted weapons for Jordanian Legion soldiers. Nasser stated that he supported the actions of the Palestinian terrorists because “they have the full right to fight for the liberation of their country.” Several days later he added optimistically and perhaps arrogantly, “we’ve returned the situation to 1956, we’ll return it to 1948.”

Back in Israel, pressure was building for a national unity government. Women demonstrators demanded that Moshe Dayan be appointed defense minister. In the end Eshkol gave in and appointed Dayan, even though he had thought to give the appointment to Yigal Alon. Begin and Sapir of the Gahal Party also joined the government, Yisrael Galili was promoted from Minister without Portfolio to Minister of Information. Haim Bar-Lev was appointed Deputy Chief of Staff. The new Defense Minister hastened to appear at a press conference, where, dressed in khaki uniform and with tremendous self-confidence he declared,” If war breaks out, I know we will win.”

On the morning of June 5, war broke out.