The return to God during the Holocaust

Hundreds of documents collected by Shem Olam Institute point to fascinating phenomenon in the shadow of horror: Assimilated Jews, some of whom had converted to Christianity, decided to go back to Judaism and die as religious Jews

During the Holocaust, while some Jews abandoned religion and stopped believing in God, and others strengthened their faith, a unique phenomenon took place in the shadow of the horror: Assimilated Jews, some of whom had actually converted to Christianity, rediscovered their Judaism.

Back to Jewish faith at time of distress

The aforementioned letter, as well as other documents and testimonies obtained by the Shem Olam Institute, reveal this unknown narrative in the history of the Holocaust.

This surprising revelation has been exposed by Rabbi Dr. Avraham Krieger, a historian and director of the Shem Olam Institute for education, documentation and research of the Holocaust.

"The story is not just loss of faith, but the profound questions those people ask," says Rabbi Krieger. "Profound questions about God, as we know, are familiar to the world of Judaism. A classic example is the mass murder in Betar during the days of the destruction of the Second Temple; Israel's wise men really struggle with the words 'the great, brave and terrible God.' And they also ask: 'Where is his greatness?' 'Where is his terribleness?' They can't say those words in a prayer.

"Faith is not robotics. The questions must be asked, and they must even be made present inside the religious language."

So what really happened there, that people felt the need to get closer to Judaism and religious faith again?

"It's really one of the most fascinating phenomena, that alongside people who presented very difficult questions or whose faith disappeared, opposite radical phenomena took place. Jews who were at the margins of the Jewish world, who suddenly decided to adopt their Jewishness blatantly."

According to Rabbi Krieger, "The situation non-religious Jews were hurled into made many of them feel that 'if I am already here just because I'm Jewish, I should at least check what it means.'

"A journal of an anonymous person from the Warsaw Ghetto, from an assimilating background of the 'Zionist circles,' as it says, is filled with expressions reflecting a sort of yearning and thirst to learn about his Jewishness. He feels the absurdity over and over, that the Jewish world is now present around him, but he doesn’t know what this baggage means to him.

"There were also people who arrived at the ghettos according to the Nazi racial laws, but were Christian. After all, Jews were defined as such up to three generations backwards. Seemingly, they could have kept the religion they were born into or were converted to from a young age. They could have also developed a hope that perhaps their religious status would save them, and perhaps the pope would wake up and deliver, and among them of all people many times we find a reversed process. People who arrived at the ghetto, at death, and wanted to go back to Judaism."

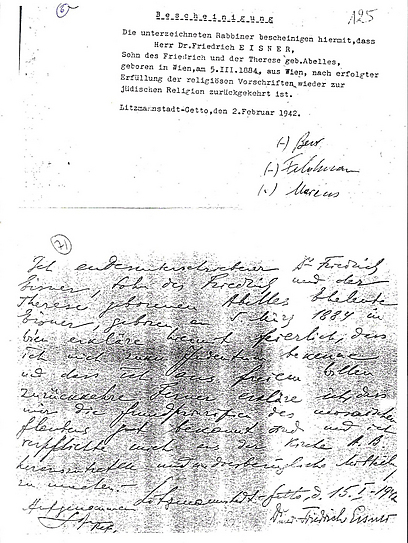

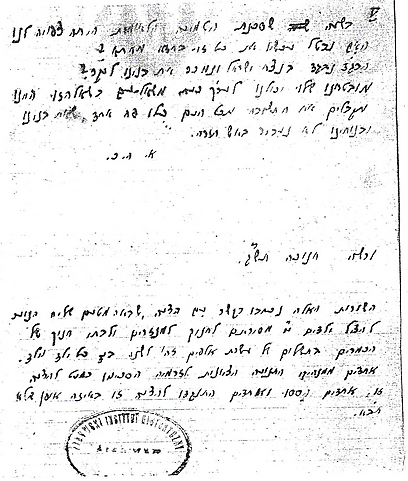

'Return to Judaism' ceremony at Lodz Ghetto

One of the documents Rabbi Krieger and his researchers found comes from the Lodz Ghetto. It tells the story of Dr. Eisner, who converted to Christianity in the 1920s. Eisner was affiliated with a church in Vienna, which he visited every Sunday. But when he arrived like many others from Austria at the Polish ghetto, he asked the rabbis to undergo a process of "returning to Judaism," mainly a declarative act which reflects the change in his religious opinions.

"Today we have the formal papers documenting the 'return,' and a letter he sent to his church in which he informed them of his decision to leave and go back to his Judaism," says Rabbi Krieger. "He, allegedly, did not have to do that, and definitely not from inside the ghetto. I see it as a statement: It's like you're showing me just how much being Jewish is an obstacle in my life, and in return I go back – and in public."

Eisner was murdered eight months after the process, as a religious Jew, in the Chelmno extermination camp.

How does one 'measure faith' in ghetto?

Shem Olam is defined today by the New York State Archives as one of the biggest research archives on life during the Holocaust. The institute has a collection of some 800,000 documents and testimonies about ideological and ethical dilemmas during the Holocaust, and is constantly in a race against time, trying to collect testimonies and stories about life and its meaning within death.

"In my eyes, these are the significant lessons which are relevant to our times too," says Rabbi Krieger. "When you only deal with death and physical survival, the ethical questions and dilemmas remain untreated and undocumented."

According to the rabbi, no "measurable and significant" studies have been conducted until now on the issue of religious faith or lack of. "From the few studies conducted on changes in opinions on religion and faith, the trend actually pointed to a tie. In other words, some would leave and others would join.

"However, it's important to remember that we are talking about a completely different reality, in which all the regular measurement rulers which define what a 'religious' or 'faithful' person means simply don't exist. Today you can check religious commitment, like observing Shabbat or kashrut. Each of these things didn't even exist there, so how exactly can one 'measure faith' in such situations?

"My father, a Holocaust survivor, once told me something which I needed five minutes to recover from – what returning to normative life meant for him: 'I went back to eating with a knife and fork.' We can't imagine five years of living outside civilization, of existing in a reality of a subhuman, an animal. Pardon me – an animal is in a better position. It's incomprehensible. So this return to the normative world is difficult and is even almost impossible."

Rabbi Krieger explains that after the Holocaust the survivors were thrown into a new reality, "and most did not try to restore the norms they had lived according to before the war. Some defined it as 'I lost my faith,' so as not to start dealing with the questions and with what happened once again.

"And here, at an elderly age, we suddenly hear testimonies from survivors who feel that they are in fact stuck in the same point in time on the eve of the Holocaust, and they are still 'there,' at least in spirit. They didn't really leave or make a change, but today, decades later, with a family, grandchildren and even great grandchildren, it's not easy to go back."

Incomprehensible religious fanaticism

"People in the ghetto began talking about the option of converting. An opportunity has been created to send the children to Christian systems, thereby saving them, but knowing that they will be lost to their people… I am sure that if it were possible for us to hold a referendum on this question, we would have received a unanimous response from the entire people: That we would not put our sons and daughters through the strange fire. Some of the movement leaders agreed, while some objected and some hesitated." (December 1942, Warsaw Ghetto)

The anonymous journal of the member of the Zionist circles in the Warsaw Ghetto reveals in full an ethical dilemma on seven pages of precious paper. It focuses on proposals from the church to hand over the children from the ghetto, who will be hidden in convents, at the price of conversion.

Krieger says he is uncertain that the words of that person reflected the state of mind in the ghetto. "There were probably many who would object. I showed this segment of the diary to Major-General Yossi Peled, who was saved this way. He was shocked at the idea that if everyone had shared that writer's thoughts, he would not have been alive today.

"On the other hand, the actual indecision is fascinating. Identity is a weighty question for them at least as much as life itself, and giving up is not obvious. It points to their deep commitment to their religious and national identity."

How much of a hold did religion have in those dark places? Rabbi Krieger says it sometimes bordered on complete irrationality and incomprehensible fanaticism.

"It could have reached places which were close to bizarre, this desire to maintain the religious lifestyle even a little bit. Like not eating certain things and nearly putting one's life in danger.

"But also abandoning religion after the war wasn't always rational. During a conversation we documented between two survivors, one asked his friend what had eventually led him to abandon religion – after fighting for it in the camps. His answer was: 'The experience of wealth is more difficult than the experience of poverty.' In other words, that wasn't necessarily rational either."

Narrative vanished or concealed?

The documents and testimonies collected by the institute raise profound questions about the absence of these narratives in the story of the Holocaust, as we know it.

"There is no doubt that the Holocaust story was engraved in the Israeli society in a very particular narrative," Rabbi Krieger admits, "and that's only one aspect of the story that isn't told."

"The motto of Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day is the most famous one of them. Today we know that heroism has many faces, which do not necessarily include holding a weapon in one's hand. A mother who protected a child from the reality of hunger is as heroic as that fighter in the ghetto.

"Shem Olam, like other research institutes, is trying to make other narratives present in the story of the Holocaust, because the current one is mainly bubble-like and is missing many parts, and by not talking about them we present a false picture, and falsity will eventually be refuted."

Was there a guiding hand here, in your opinion?

"I'm trying not to blame. It doesn't always come from a conscious place, although there is no doubt that some of the concealment was intentional. History is a tool for shaping the present. It presents heroes and conceals others, and we see it also in the late documentation of the wars of Israel, for example.

"The questions of faith and 'other' narratives could have disrupted the classic story we are being told, like that 'the Diaspora world was never optimal compared to the Land of Israel ideal.' So speaking about strength of spirit in this world may subtract part of the ethos built on their back.

"In addition, the story of the Holocaust was in the hands of historians who were unfamiliar with this world, the religious world. I once sent material on the matter to one of the Israeli professors who specialize in it, and he answered me: 'I dealt with issues close to my heart, you deal with issues close to your heart.' And indeed, that's what happened, but while people were busy commemorating the parts close to them, the other parts simply disappeared from the discourse."

Rift in Jewish identity has yet to heal

Rabbi Krieger says that during his trips to Poland and other countries, he meets people who are victims of the same identity struggle.

"I Lodz I was approached by a priest in a church, no less, whose mother told him before she died that she was Jewish. He was in a crazy dilemma and didn't know what to do. I found out later that he stood in front of the entire community in church, told them that he was Jewish, and left everything. He hasn't found himself to this very day, and he's not the only one.

"It's important to know that some people are torn until now as a result of what they had to cope with there. My goal is to raise the 'other' stories. It took a while before the survivors could even talk about the Holocaust, and it probably takes longer to talk about what didn't match the dominant narrative. I believe these stories must emerge, and that from there history will already balance itself."