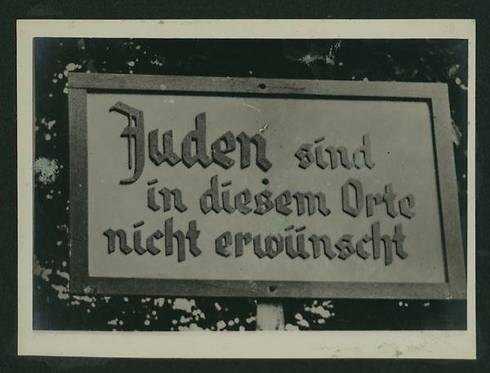

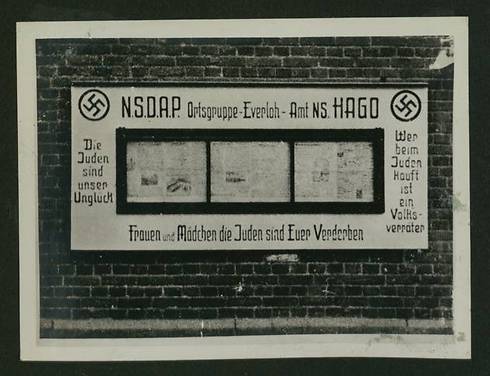

Photos reveal rising anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany in 1935

Eighty years ago, two Jewish journalists sent a Dutch photographer to document anti-Semitism in Third Reich and expose true face of Nazi party to the world, but international media didn't print photos.

Eighty years ago, a Dutch photographer went into Nazi Germany to collect evidence of the raging anti-Semitism in the country, sent by Jewish journalists who were hoping to alert the world to the situation in the Third Reich, before it was too late.

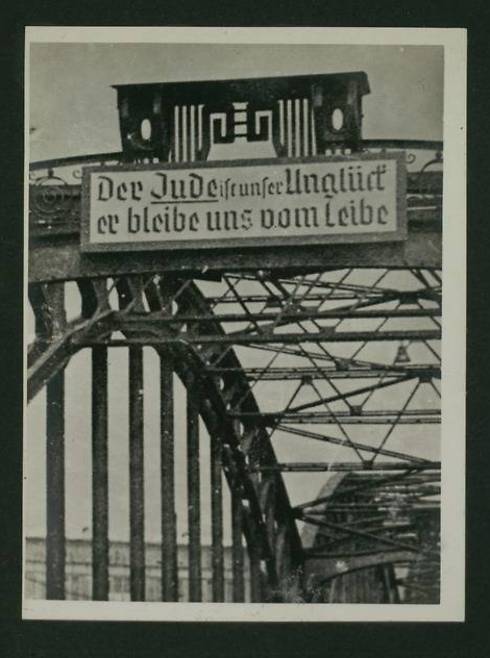

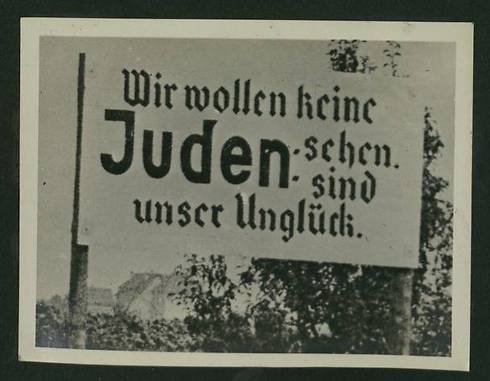

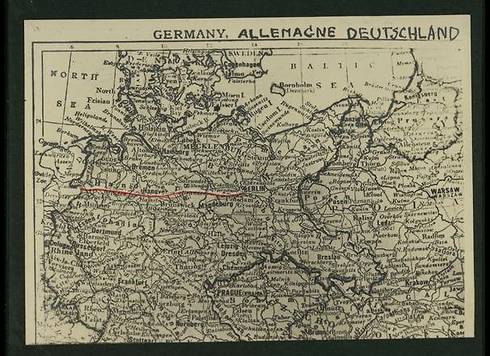

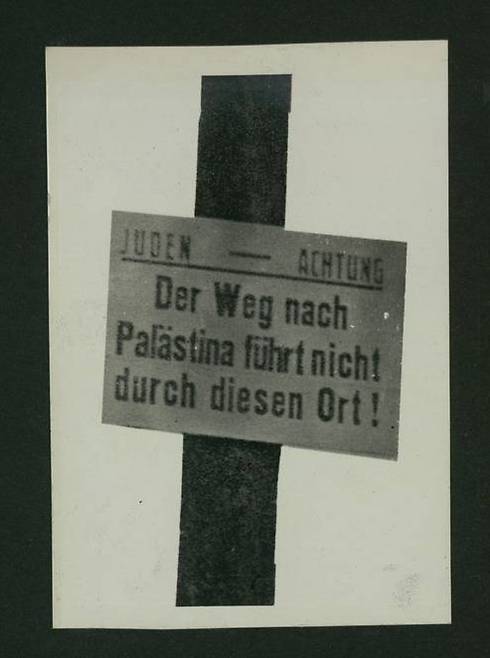

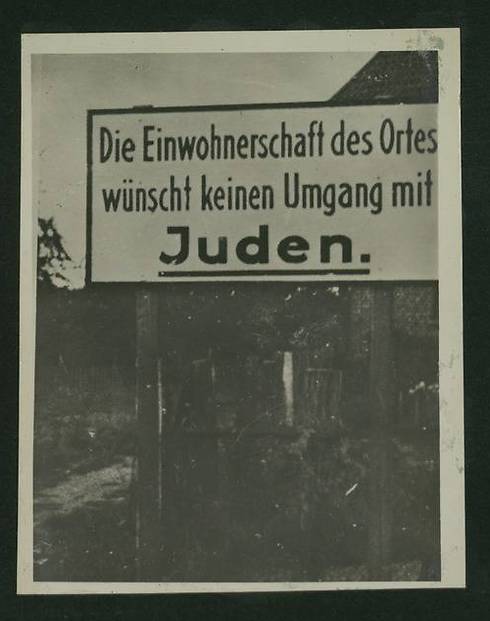

The photographer crossed Germany on a motorcycle in 1935 and documented signs along the way, all with one unified message: "Jews are not wanted here."

The Dutch motorcyclist photographed 22 signs along the road connecting the border town of Bad Bentheim to the capital Berlin, some 500 kilometers away. He found them on the sides of the road, in entrances to villages and in front of picturesque houses.

But the photos, which were distributed to media organizations all over the world - including in the Land of Israel - did not produce the desired reaction.

"It was a war that was doomed from the start," according to the National Library in Jerusalem, where the photos have been kept all these years.

The photos are coming to light now, ahead of the International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

The Dutch photographer, who remained anonymous, was sent into Nazi Germany by a news agency formed by two Jews who escaped Germany to the Netherlands - Hans Richman and Alfred Viner. They had one main goal: To expose the true face of the National-Socialist Party that came to power in those days.

"The photographs were meant to stir as much publicity as possible, to make people aware of what's going on in Germany, but even in the Land of Israel they didn't understand what they were being warned from," said archivist Gil Weissblei.

In January of 1936 Richman and Viner also sent an album with copies of the photographs to the National Library in Jerusalem, in the hopes of raising awareness in the Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel.

The photo album was filed at the National Library, where it collected dust over the years and was seen by only a handful of people. The newspapers in the Land of Israel did not print the photos.

"It's possible the journalists then didn't think this was a story," Weissblei said. "They were used to displays of anti-Semitism and it didn't seem like something special to them. They didn't imagine where this would lead."

"It's only today, in hindsight, that we understand the significance of these photos. You may not see skulls, blood or murder there - they're just texts - but they led to one of the greatest crimes in human history," Weissblei went on to say. "We can also see that many of the signs were an initiative taken by the locals, who accepted it and viewed it part of the norm. It's a testament of the levels of hate that eventually led to mass murder."