An Egyptian voice in Tel Aviv

Haisam Hassanein, a master's student from Egypt, gave a touching speech about his experience studying in Israel at his graduation ceremony in the Tel Aviv University; now, he talks about what made him come here: 'I came to see for myself what Israelis were like,' and his desire to become an ambassador of goodwill: 'I think I have a lot to offer.'

It was only when he was sitting down to fill out the application forms for international students applying to Tel Aviv University's Middle East program, a little over a year ago, that Haisam Hassanein decided to tell his mother about his plans. She wasn't enthusiastic about it, to say the least.

"Don't go to Israel, I'm really scared," she begged. "Despite the peace agreement, our conflict with Israel hasn't ended. The Israelis don't like us and we don't like them. Besides, it's dangerous there. Who knows if they even speak English there, and if there is running water."

But the son insisted. "I totally understand you," he told his mother, whose name he refuses to reveal, "but I have to know who the Israelis are. I promise to be careful: I won't let anyone deceive me or drag me into something with negative repercussions."

They both knew what kind of dangers an Egyptian student in Israel could face: They suspected Israel's intelligence agencies would contact him and try to recruit him as a spy.

"Don't talk to anyone," the mother warned. "If it's so important to you to study in Tel Aviv of all place, go to lectures, study, but don't make friends, and keep to your room. Don't have contact with strangers, even if they are nice."

And she had another firm warning. "There are particularly beautiful women in Israel," she said. "And I don't want you to bring home an Israeli girlfriend. Be careful, don't let them drag you into the trap of intelligence agencies."

Two weeks ago, the 24-year-old Haisam Hassanein reached an impressive achievement when he represented his class as the valedictorian, giving an emotional speech at their graduation ceremony, but ten months ago, things looked vastly different.

The New York office of the international students program gave him documents meant to make his entrance into Israel easier, but when he landed at Ben Gurion Airport, these documents did not help.

"Someone from security took me aside and went over the Egyptian stamps in my passport," Hassanein says. "He asked me: 'You're Egyptian? What makes you want to study here?' I told him: 'Because after all I've heard about you, I'm curious to get to know Israelis.'"

The conversation continued, but was a pleasant one. At a certain point, Hassanein could no longer hold himself back. "Don't you think I'm a special guest?" he asked the security guard. "Don't I deserve to be welcomed with flowers?" After that he took a taxi to a hotel in Tel Aviv.

"It was definitely scary," he recounts. "Two days later I got to the Tel Aviv University campus and they sent me to the lady that manages the students' dorms. She gave me a key to a two-room apartment that I shared with my roommate, a student from Poland, and I've been here ever since. Every morning I wake up and cannot believe I am in Israel."

'I was afraid I was being eavesdropped'

Haisam Hassanein grew up in a town in Banha in Egypt, 45 kilometers north of Cairo, until he was 16 years old. "But I don't even know Cairo," he says. "I've only been there once, when school took us to visit a museum. Since then I've only been on a bypass near Cairo, on the way to the airport."

He attended primary school and high school in his childhood town, and when his father accepted a job offer to work as an engineer in a factory in Pennsylvania, the family moved to the US. Four years ago, his father died in a car accident. The last thing Hassanein wanted to do was make his mother worry, and that is why he obeyed the strict instructions she gave him before he left for Israel.

"From the very first day here I created a bubble for myself and kept to it, just like she wanted," he says. "I didn't have any unnecessary conversations and rejected anyone who tried to get near me. I was suspicious and kept quiet. When the school day was over, I'd go straight to my dorm room. On weekends, I'd take the bus on my own, looking at Israelis and keeping my distance."

"This withdrawal from society put me in a difficult situation. People around me wanted to meet 'the Egyptian,' tried to befriend me, but I pulled back. I wasn't open to talking to them. The interesting thing was that people actually understood what I was going through, and didn't press the matter. That situation lasted for two months. During that time, I observe my surroundings, learned a lot of new things, and gradually I stopped being afraid."

After two months, Hassanein started suffering from the seclusion he condemned himself to. "I realized I created a problem for myself: On the one hand, I'm in a new place, alone, without my family; on the other hand, I thwarted off any attempt to befriend me. Because of the negative baggage I had against Israelis and the warnings from my mother, I didn't trust anyone.

"There were moments I really regretted this adventure. When you apply to a prestigious program, you don't think about the personal aspects. It wasn't easy for me to go to the university's sports center on my own. It wasn't easy to wander around Tel Aviv alone and see all of the people sitting in restaurants and cafés. Once a week I'd call my mother in Pennsylvania, and she always sounded worried. She would interrogate me: 'What's going on with you? What are you going through?' But I didn't tell her about the difficulties. I only said: 'Thank God, everything is okay,' and intentionally avoided having long phone calls because I was afraid I was being eavesdropped."

Best friends

The ice began to break when Hassanein finally accepted the persistent offers of a Jewish-American student to take him on trips around Israel and explain Israeli society to him. Then there was an Arab student from Nazareth, who explained the Israeli Arabs' situation to the Egyptian guest and how he sees, for better or for worse, the coexistence between Jews and Arabs in the country. There were also two Palestinian students who took him on a tour of the divided Hebron.

"I also developed great ties with two amazing Israelis," Hassanein says. "One of them is Doron Tzafrir, an actor at the Arab-Hebrew Theater in Jaffa, who took me to see plays in Jaffa and Haifa, showed me around Daliyat al-Karmel, and introduced me to his Jewish and Arab friends. During the elections, he took me to Labor and Meretz events, sat next to me and patiently translated the candidates' campaign platforms."

The second Israeli friend asked not to be named, and Hassanein respects his wishes. "That guy came to me and tried to have a conversation with me in the Egyptian dialect, but he had a lot of mistakes. So we made a deal: He would take me to interesting places, and I'll talk Egyptian Arabic to him and correct his mistakes. He introduced me to his wife and children, and we've been the best of friends since - traveling together and eating a lot of hummus. He's the one I turn to in Israel with any problem."

So far, Hassanein has visited Nazareth, Haifa, Druze villages, Acre and Kibbutz Alonim - where he traveled as a part of an organized group. "I heard there was a group of American Jews who are going there, and asked if I could join. The immediately told me: 'You're welcome to come.' We drove all night to track the cattle thieves; we stayed until 6 am and conducted lookouts. In the end, the thieves did not show up."

At a restaurant in Daliyat al-Karmel he had a unique experience. "When they heard that 'the Egyptian' arrived, two waitresses came up to me and told me they were from Egypt and that they were excited to meet me. And then the Druze restaurant owner came up to me and told me something I'll never forget: 'My brother was killed in a war against you in 1973, and after he was killed, I left my unit in the IDF and came back to help my family deal with the grief.' I was so shocked I didn't know what to tell him, but he didn't make me feel unwelcome, so I said: 'Look, it also happened to thousands of families in Egypt. It's a good thing we have a peace agreement now.'"

There were other conversations that were etched into his memory. "I went to an election gathering of one of the parties with friends, and someone who was in the audience came up to us. I told him I was from Egypt and he gave me a paralyzing stare and said: 'So what? You hate us.' There were other cases, when Israelis heard where I was from, and told me in anger: 'Now you see the reality in Israel, but why would they believe you in Cairo and Alexandria?' They also warned me that before my visit to Israel, Egyptian intellectuals visited the country and when they went home, they were slandered.

"I'm definitely aware of the negative image Israel has in Egypt. A month before I got here, I flew to Egypt to visit my family and didn't tell anyone about my plans to study in Tel Aviv. In Egypt, they're sure that you are only occupiers, baby killers or spies all over the world, including in countries that you have a peace agreement with."

Throughout his ten months in Israel, Hassanein didn't contact his family in Egypt, "so they won't get in trouble." He also didn't make any contact with the Egyptian Embassy. "But it's important for me to stress that I didn't do anything here that is harmful to Egypt. I'm not the first Egyptian to come to Israel, and probably not the last either."

'I was trembling with fear'

The idea to have Hassanein speak at the graduation ceremony came from the directors of the university's international students program. They were looking for a valedictorian, and found Hassanein."I remember a lady called Haya Binyamin approached me and asked if I wanted speak at the ceremony, and I asked her if the university administration was really going to allow me to do that. She asked: 'Are you interested?' and I said: 'Yes, absolutely,' even though at that moment I had no idea what I was going to say."

He says work on the speech took a month and a half. "Throughout that entire time I wrote drafts and tried to articulate the message I wanted to convey - that despite everything we were taught, we don't really know each other. I wanted the speech to express the special experience I had over the past ten months in Israel."

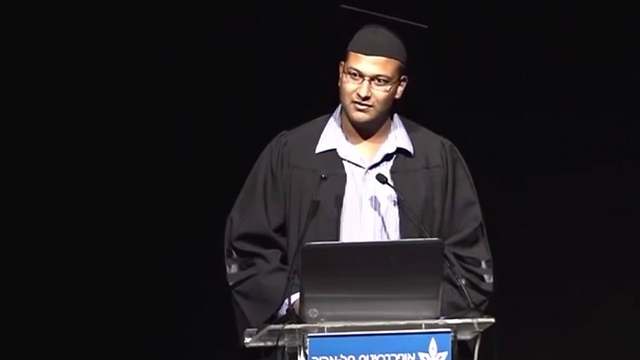

He came to the ceremony wearing a black gown and a mortarboard. The mounting excitement made him sweat. At the ceremony, 400 graduates and their families, along with the senior academic staff, were waiting. His Israeli friends were also in the audience, cheering for him. In Pennsylvania, his mother and two brothers were watching the live broadcast of the ceremony on the university's website. He was introduced by the international students program's director, Maureen Meyer Adiri. "I would like to invite the valedictorian, Mr. Haisam Hassanein, a master's student of Middle Eastern studies," she said.

"I was trembling with fear," he says. "It was the first time in my life that I gave a speech in front of such a large audience, and in Israel of all places. It was exciting and scary. When I started talking, there was complete silence. Everyone was listening to me, and because of the spotlight on my face I couldn't see the audience's reactions."

He says he was surprised with the roaring applause, which lasted for several minutes. During his lengthy work on the speech, as he wrote and rewrote and corrected his wording over and over again, he did not know how the audience will respond to it. Among other things, he said in his speech: "My first exposure to Israel was through music and television," hinting at the popular song "I Hate Israel" and TV shows about Mossad agents who keeping falling into traps set up by their Egyptian counterparts.

After his speech, he went off the stage to join his fellow graduates. "Everyone came to shake my hand and said they were very touched," he says. "It was a shame my family wasn't present, but when I called home, my mother surprised me and said: 'I'm very proud of you.'"

A great honor to the university

That very night, the speech was uploaded to YouTube and has garnered over 120,000 views so far, 30,000 of them in the United States and 27,000 in Egypt.Egyptian newspapers reported the speech, and most of the responses were negative. Hassanein was called a "traitor," some accused: "After you couldn't find your place in Egypt, you sold your sole to the Zionist enemy," others claimed he was a CIA agent cooperating with the Israeli Mossad. There were those who believed that President al-Sisi, who used to head the Egyptian Army's Intelligence Corps, recruited Hassanein to gather intelligence, while others hurled abuse at him and cursed his mother.

Next week, Hassanein will go to Pennsylvania to visit his mother. During his time in the US, he will also visit the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, where he worked as a research assistant. It was there that he decided to study in Israel.

"And when I return to Israel in two months, I'll start working on my PhD thesis," he says. Hassanein wouldn't reveal the topic of his research, but proudly says that his doctoral advisor will be Prof. Shimon Shamir, who founded the Israeli Academic Center in Cairo and later served as Israel's ambassador to Egypt. "It's a great honor for me," Hassanein says.

In addition to his academic ambitions, he also wants to be a goodwill ambassador to bridge between the two sides. "I believe I have a lot to contribute," he says. "Now I know that Israelis are people like everyone else, who want to live a good and secure life, who want peace with their neighboring countries. The problem is that there is no trust on either side. They don't talk to each other enough."

Prof. Uzi Rabi, the director of the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and Africa Studies at Tel Aviv University, has nothing but praise for the Egyptian student. "Haisam is definitely and incredible guy," Rabi says. "He's a very talented guy, an excellent student who won't let either side off easy. We'll be happy to aid him in his doctorate thesis and welcome him to our team at the Dayan Center. He brings great honor to Tel Aviv University."