Israel losing fight against 'Facebook jihad'

Three months into the current wave of violence and it is clear the incitement on social media not only encourages the terror attacks, it also provides instructions on how to commit them. So why isn't Israel, the cyber superpower, using its advanced technological capabilities to stop it?

One of the most shocking videos that has been making the rounds on social media over the past few weeks reviews, in blood-chilling detail, how to commit the optimal stabbing attack against Jews.

"Your little finger must be placed on the edge of the knife's hilt, to stop the knife from slipping," explains a masked man in a cold, mechanic voice, and then goes into greater detail: What stabbing movements are the best, which area in the body it is best to aim at, and what to do with the knife after stabbing, all so it would "cause the greatest amount of damage possible in the enemy's body."

Another video from the same "series" provides even more recommendations, including spraying K300 on the knife, to maximize the damage.

It's unclear how many views these videos got, but it is safe to assume that if they made their way beyond Facebook to WhatsApp and Twitter, the numbers are very large. The indictments and the information that is piling up in the Shin Bet's interrogation rooms show that many of the attackers in recent weeks watched and "learned" from videos like that.

And here is something that is less known: Israel - if it only wanted to - could have, most likely, caught the people behind these videos and those spreading them. In fact, Israel now has the technology to stop a considerable amount of the incitement on social media, and in many cases to apprehend the people behind it - and bring them to justice.

Except it almost never happens.

This Sunday would mark three months to the incident that Israel's defense establishment considers the opening shot of the current wave of violence. All of the security officials in the field, with whom we spoke while researching this story, agree: What fuels the terror attacks is incitement, and primarily incitement on social media.

On every corner of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram one can easily find tutorials like the aforementioned video, and there are crueler ones still. At the same time, racist cartoons that could easily have appeared in the newspapers of the Third Reich are everywhere, and insane and delusional blood libels garner a frightening amount of "shares." Even Arab pop stars are competing among themselves in an attempt to write the most extreme song that would win over the hearts of the masses.

"We can say with certainty that quite a large part of the attackers, even those who were killed, are not people motivated by deep-rooted ideology," a senior intelligence official told us this week. "They were suffering from one kind of personal problem or another. And that is exactly the problem with incitement: It will mostly get those with the personal problems and affect them in an extreme way, driving them to commit terror attacks."

With that being the case, it would make sense for all of Israel's cyber-fighting bodies to be recruited to battle against this phenomenon. But in reality, and despite the fact Israel is considered an international cyber superpower, the activity of all of these cyber-fighting bodies has hardly had any effect on the wild incitement prevalent online.

A Yedioth Ahronoth investigation found that despite the fact hundreds of experts in the different security agencies are working on this issue, eradicating social media incitement is at the bottom of the list of priorities. Why is that? Each agency has its explanation. Military Intelligence and the Shin Bet say: This isn't our job. We deal primarily with stopping terror attacks; the Israel Police says: We're not an intelligence agency and we don't systematically monitor the information like Military Intelligence or the Shin Bet do, and that is why we cannot investigate the matter. And so forth.

Meanwhile, while security agencies are busy passing the responsibility from one to the other like a hot potato, the numbers are very clear: Since the beginning of the current wave of terror attacks, some 2,000 people have been arrested; out of those 2,000, only 55 were arrested on incitement charges - meaning some 2.75 percent. That's it. From these 55, only 16 were incited for incitement.

The big question is now: Why is that?

A cyber arsenal

The Israeli public treats incitement on social media as a kind of wild weather hazard: It's hard, it's there, and there's nothing that can be done about it. Perhaps other than wait for spring. Except that reality is completely different.

"First of all, let it be clear: We are a superpower in our technological intelligence capabilities," explains Dr. Nimrod Kozlovski, one of the top cyber security experts in Israel. "The State of Israel's intelligence agencies developed several capabilities, very few of which were made public, but many of which won Israel Defense Prizes."

Without getting into details, what are we talking about?

"We can produce quality intelligence from conversations and we do so with a variety of measures. In the case of incitement, for example, we can learn about the existence of inciting content and we can even learn of the sentiment, meaning if the content is negative or positive. It saves a lot of time, money and manpower. We also have very advanced tracking capabilities, for example, if someone writes something on an anonymous forum."

Dr. Kozlovski says that at the moment, these systems are mostly being used for monitoring and analyzing of the general mood. So, for example, the systems can identify an increase in internet traffic and analyze what it means. If after a terror attack there is an increase in traffic and comments on certain websites, the system can tell if this is a show of public support of the attack, or a condemnation of it.

"In the intelligence field, this has very great value," Kozlovski continues. "It is actually comments that appear non-violent to us, or comments made by people who are liking or sharing something, that allow us to mark operatives and help our intelligence agencies a lot."

"There are actually three levels to this activity, that our intelligence agencies can do against terrorism in general and incitement online in particular," says Prof. Gabi Weimann from the Department of Communications at the University of Haifa, who has been researching terrorism on the internet for 18 years and gives lectures to security officials from different agencies. "It's called the MUD model - Monitoring, Using, Destruction."

What does that mean?

"On the first level, monitoring is done. I don't take down a website or attack it, because it's an excellent source of intelligence. But I browse it and collect materials. The Americans, for example, used that a lot to monitor al-Qaeda.

"The second level is using or interfering. For example, interfering with the content can be done with a campaign against the narratives presented by the terror group. You can, for example, turn to these groups and try to present them with different content. This is a shadow war that no army would admit to.

"The third level is the destruction of internet activity. Security officials know that these websites can come back online very quickly, but they slow the websites' activity and destroy some of the pages they don't want online at all."

So we have great capabilities, but how much do you think these capabilities are actually being put to use in the current wave of violence?

"It is my impression that not enough is being done. Everyone can see the incitement works for the Palestinians, and we haven't been able to defeat them. Even in the research we do on the internet, we don't see any signs of sophisticated counter-campaigns. In my in-depth browsing of social media I would expect to see the three types of activities I mentioned. Of course, it could be that I don't see some of these things being done, but what I do see is a 14-year-old girl stabbing with scissors. After all, she didn't spend time with a terror organization; she was exposed to incitement on social media."

Who's in charge here?

So technologically, the capabilities needed to fight online incitement to terrorism exist. Obviously, it's not reasonable (and there's also no need) for them to be used against every eight-year-old who likes a jihadist video, but there's quite a good chance to find those who created the video and the first to spread it. Now we're only left to wonder why this is not happening.

The Shin Bet, for example, realized a long time ago that the internet is one of the main arenas of modern fighting, and the agency dedicates a lot of manpower and resources to that end. But the Shin Bet is not really all that interested in incitement in and of itself.

"The agency, which has a presence on social media, is looking for the organizations, the plotting of terror attacks, the recruiting for these organizations," explains Lior Akerman, a former division head in the Shin Bet. "If they see incitement, it is being treated as a sign that indicates on or leads to something else. As far as I know, the agency doesn't at present have any orders, or legal authority, or the ability to enforce when faced with a Palestinian posting incitement. I don't think, and I'm not sure, that the Shin Bet can even deal with that."

Why?

"Because there aren't enough resources to cover it all."

If the Shin Bet can't deal with it, then perhaps the Israel Police can? This might be a good time to mention: Incitement to violence and terrorism is against the law. Section 144 of the penal law explicitly states: "He who publishes a call to commit an act of violence or terrorism; or words of praise, sympathy or encouragement of an act of violence or terrorism; support of it, or identification with it... will be imprisoned for five years."

But the Israel Police, our investigation found, is monitoring social networks only in a half-voluntary capacity. The police's new media people - most of whom have no training as cyber investigators or as intelligence agents - are the ones who receive the complaints sent by angry citizens about the unchecked incitement raging on social media.

The police also have an impressive cyber unit, which is a part of its elite Lahav 433 unit, which includes over a hundred internet experts, some of the best in the field. But this unit doesn't deal with incitement at all; it handles cyber crimes like fraud and impersonation.

According to a security official, since the beginning of this wave of terrorism, the number of investigations opened into incitement to violence and terrorism by the cyber unit reaches the dizzying number of zero.

The unofficial explanation is that these investigators have no relative advantage on others when investigating online incitement, so it's a shame they'll waste their time on that.

So if the police and the Shin Bet can't deal with it - we are left with the IDF. With the lack of quality police intelligence in the field of online incitement, the only other body besides the Shin Bet that monitors activity on social media is the IDF - mostly using the new cyber division in Unit 8200 and different units in Military Intelligence. Except that the military doesn't view the prevention of incitement as a goal, as we were told by a senior official this week: "For us, the focus is more on hostile destructive activity (terrorism) and less on propaganda. If the intelligence officer thinks there is an activity that goes beyond incitement, he looks into it, but there's no division that gets up in the morning and their job is to take Facebook pages and point them out to the police."

So what do you do? It's hard to believe the IDF sees a post calling to murder Jews and just lets it go.

"It depends on a lot of variables. For example, we see if the person doing the incitement has permits (to work in Israel - AS). We tell him: If you don't stop, we'll take your family's permits away. It's not clear cut, but generally the Shin Bet and the IDF play a secondary role on this, it's not being led by us. We care about terror activity. There's also a matter of effectiveness. It's a shame to send people to arrest someone at night, only for the prosecution to release him in the morning. We don't want revolving doors here. It also gives them fuel against us, as in 'you want to shoot? Shoot, don't talk,' and don't make arrests in vain."

So the Shin Bet is monitoring online incitement, but mostly in order to thwart terror attacks; Military Intelligence is also monitoring, but if they come across incitement - it might not even be reported to the police; and even if it is reported, the police - whose cyber activity focuses on cyber crimes - will probably not do much with that information. It's the classic Israeli saying of "it's not me who's in charge - it's him," except that this time the price is teenage terrorists who take a screwdriver and go out to become martyrs.

Former Shin Bet official Yaron Bloom: "There's a problem with the division of responsibility: Who takes responsibility over what. It's not a case of 'now I'm in charge of Syria, you take Lebanon.' The division is not that dichotomous. I can say about the Shin Bet that their resources are limited and they have to prioritize. They don't have the ability to handle everyone who post incitement. Even when you plan on doing something dramatic, it would only be against really extreme online activists. You can't fight everyone. You can't handle every kid. But if you see someone, let's say, from Umm al-Fahm, and the investigation finds that people are being incited by him, he'll be arrested and prosecuted. However, if it's just someone who's not worth a dime, there's no point in wasting resources on him."

Are the issues between the organizations (Shin Bet, IDF, police) part of the disease that afflicts our defense establishment - the ego wars?

"I'm a big believer in cooperation between organizations and think that today these wars don't happen as much. People in the State of Israel realized that you need to put your ego aside and work together. It's important that we are there, online, and cooperate: You cover A, I'll cover B. Let's have a joint team, let's form a special investigative team, see where it takes us. The moment the division is clearer, people know what they're doing, because otherwise we'll do the same things. There might also be a situation in which we are both watching the same website, a blog or a page that interest everyone, and since you keep the information to yourself, or the tools at your disposal, then you don't share the information. We keep looking for things to fight about. Both the police and the Mossad have excellent capabilities in the cyber field - and it's important to cooperate."

The police's cyber unit has opened zero investigations since the beginning of this wave of terror attacks.

"I didn't know that. That's surprising. I'm convinced (new police commissioner) Roni Alsheikh will put them back in line; I promise you they'll change their perception and realize they need to attack. If you, as a policeman, identify an activity that is considered incitement, you have to open an investigation, and not need to have an intelligence agency push you to do it."

Prof. Weimann, you are not part of the defense establishment. What do you think of this mess?

"We haven't invented the problem of the division into areas of responsibility. It's one of the major problems in the United States, and there are several American agencies that are dealing with the war on cyber terrorism. In many cases they don't share information with the others, out of considerations of inter-institutional prestige. We don't have anyone to integrate everything together, and the issue falls into the hands of several agencies, each aiming the focus where they need. So, for example, the police's cyber unit deals mostly with cyber crime, and the words 'terrorism' and 'security' don't come up there at all. We don't have a strategy or a boss."

Freedom of speech or freedom of incitement?

Besides the lack of resources, the problem of separate areas of responsibility, and the inter-institutional ego wars, there is another major problem security officials point to in the war against incitement: The legislation on the issue, and its enforcement.

"A guy like that, who spreads materials on social media, is brought like a hero to the Russian Compound (which is mostly used by police and other law enforcement agencies - ed.) so police can hold him for eight hours and then release him," says a security official. "You have to invest in his transportation as well, just think how much logistics you need from one checkpoint to the next for someone who has no legal efficacy. So sometimes we prefer to come to his house at 3am and bother him, and then his motivation decreases exponentially."

Would you also like to see a change in legislation?

"Absolutely. I think in this case the legislator did not provide the proper tools to law enforcement, the prosecution or judges. If there was a mandatory sentencing that anyone who calls on Facebook for the murder of Jews goes to jail for five years, I'm not so sure incitement would continue unabated."

"There hasn't been any dramatic change to the law," says former Shin Bet official Lior Akerman. "Just like before Rabin's murder. Incitement was spread freely, people weren't investigated, no one dealt with them, punishment was not strict, and that's the situation today as well. Police also has a problem here because there are places in which it cannot operate and it needs authorization from the prosecution to open an investigation into incitement. And, really, what is incitement? In the State of Israel, in order to prove something is incitement and reach the point of sentencing, there are a lot of stages, and even if police gets through them, the punishment is very light."

We decided to check just how much this claim, that the courts are lenient in punishment, is true. The courts' computerized system does not provide statics on the verdict given to each type of offense. But it is possible to examine the verdicts given and, as expected, there aren't a lot of them on the issue of incitement. The investigation we conducted found that punishments given are somewhere between community service and one year in prison, and even that is very rare.

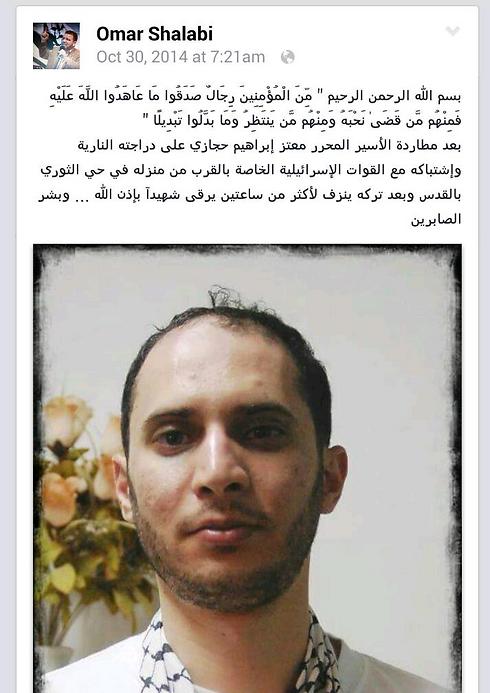

An example of that is the verdict given in the trial of Sami Dais. According to the indictment, after the shooting of right-wing activist Yehuda Glick, Dais decided it was a good idea to congratulate the shooter in a post on Facebook: "May Allah bless the womb that carried the martyr leader." The indictment further claims that he shared a song whose lyrics include lines like "Run away, Zionist, because soon you will be killed by a car," and generously complimented the perpetrators of the terror attack at the Har Nof synagogue in Jerusalem.

Dais may have admitted to the charges, but alongside the criticism he received in the verdict, the court also ruled that: "The freedom of speech is a supreme value in our country as a democratic and freedom seeking state," and sentenced him to eight months in prison. By law, the punishment for incitement to terrorism could reach up to five years in prison.

The next battle: Israel vs. Facebook

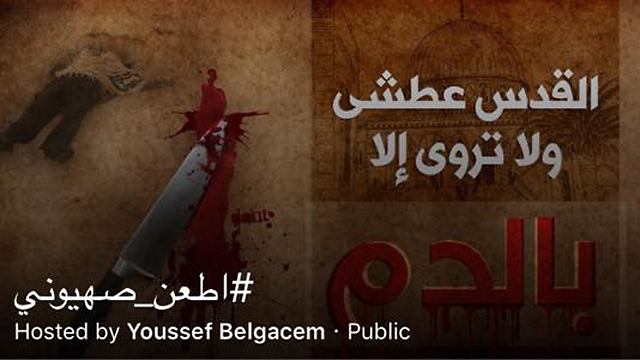

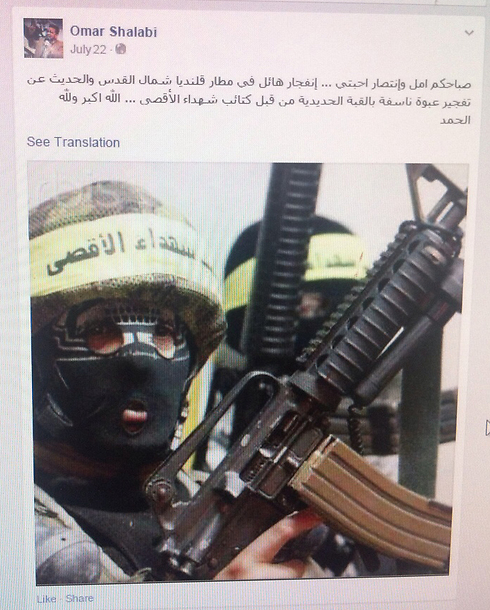

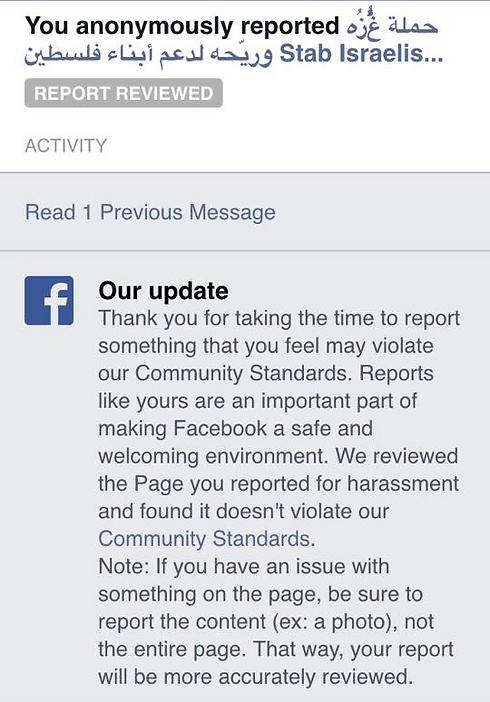

Meanwhile, until the defense establishment decides who needs to handle the incitement and how - the fight continues under the radar. Two weeks ago, the Shurat HaDin NGO filed a lawsuit against Facebook in the US on behalf of 20,000 Israelis who suffered from incitement on social media. Shurat HaDin has provided us with some of its correspondence with Facebook of their attempts to take down inciting pages.

The correspondence reveals that in many cases, Facebook refused to take down the pages, even though in some of them - like in the case of a page called "Stab Israelis" - it was pretty clear what their focus was.

"You are onto a very real problem," says former Shin Bet official Yaron Bloom. "Anyone can write whatever they want and the social media sites don't even care. I believe we will find solutions to that as well."

One of these solutions might come from Haim Vismonski, head of legislation, law and technology at the State Attorney's Office. Vismonski created a team in the Justice Ministry that deals with incitement on social media. "It's an entirely new way of thinking for the State Attorney's Office," he says. "We don't look for the criminal, but rather ask to remove the forbidden inciting content, out of an understanding that this wave of terrorism is fueled by an atmosphere created on social media that encourages the lone wolf attacker to go out and stab."

What are you actually doing?

"We turn to the service providers that host this content on their platforms, and ask them to remove the forbidden content. The first option is to act in line with the law in Israel and try to get a judge's order to remove the content - but even if we got such an order and sent it to the foreign service provider, there's still the concern they won't respect the order, claiming they are not subject to Israeli law. The second option is that of submitting requests to remove the content based on the service providers' terms of use. Our activity with the different providers is developing on this level."

And it works?

"We're trying to reach cooperation with the providers out of the understanding that they too would prefer clean dialogue online. We work under the assumption that the providers also understand that if the conversation includes pedophilia, terrorism and the likes, people would abandon the service. If the web is too 'dirty,' then normative people will flee these places."

So far, this initiative has seen success with several pages. Among others, a Facebook page calling to throw Molotov cocktails (firebombs) that had over 11,000 likes was taken down; a page called "The Pulse of the West Bank," which called for an escalation in fighting, was also taken down; as were several other pages, all with a lot of likes.

How many pages were you able to taken down since the beginning of this wave of violence?

"On the first try, the State Attorney's Office was able to take down over 50 pages, with a 70 percent success rate. Some of these pages had thousands of likes."

Experts in the field have welcomed Vismonski's initiative, but claimed this was just a drop in the ocean.

Prof. Weimann: "In the toolbox of the fighter against virtual terrorism, the legal side, including turning to Facebook, is one of the screwdrivers. And you can't build a house with just one screwdriver. It is only partially and marginally effective. Even the pages that are taken down reappear within two days."

Security officials also had criticism against the initiative. "This fight on social media is very problematic," says Yaron Bloom. "You have a guy sitting in Amman, Uzbekistan or Chechnya and inciting against Jews. What can you do about him? Do you start corresponding with the Justice Ministry, for them to write to Facebook about this or that guy? It takes a long time, and it's very ineffective."

Dr. Vismonski rejects the claims: "You can also say the fight against crime is not effective enough, because you prosecute one drugs offender and another one pops up. Enforcement is a complex thing and there's no solution that gets it all done in one go."

There is one claim that is hard to argue with: Your welcomed work is still a drop in the ocean of incitement.

"You can claim that even before a baby is born, he doesn't stand a chance, but we think the work of removing content, which is still in its early stages, has a significant chance of becoming a central tool in dealing with incitement and support of terrorism online."