High Court considers home demolition for Jewish extremists

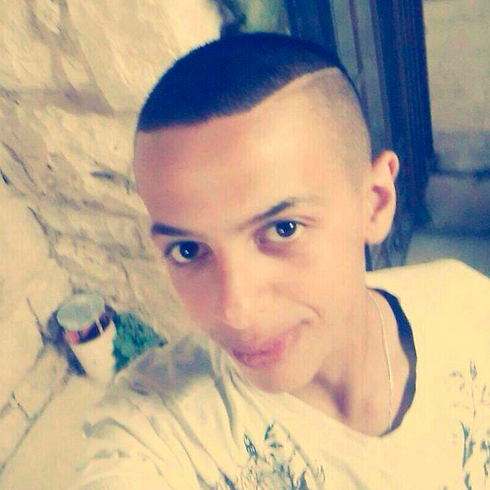

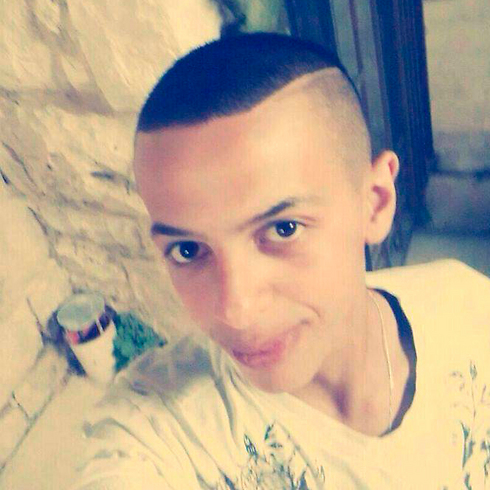

Discussions held in light of a petition filed by family of Mohammed Abu Khdeir calling for the demolition of his murderers' homes; state lawyer argues policy not warranted as a deterrence measure, while family attorney cites 'double standards.'

The policy is frequently carried out as a deterrence measure against Palestinians who have committed terrorist attacks.

During the discussions, the High Court justices posed difficult questions to representatives of the state by asking if, and why, different protocol should be applied to Arabs and Jews committing acts of terror.

“There can’t be double standards. There has to be a demolition of the houses of murderers,” said the lawyer representing the Khdeir family.

The state representative rebuffed the point by stating that the demolitions are designed to serve as a deterrence and prevent the next murder.

Taking this point further, Justice Neal Hendel responded by asking, “What does it matter to me if it is an Arab or a Jew?,” if indeed the policy is intended to prevent a murder. “If we say that we are prepared to employ this policy against a specific group of people and not against another it raises certain problems.”

Offering an answer to the question, which has long been asked in the Israeli establishment and society as a whole, the state lawyer cited the revulsion felt by the families of Khdeir’s killers which rendered the need to issue a demolition order pointless.

“It is said that in Arab society there are more supporters and that the deterrence will be infinitely stronger,” said Elyakim Rubinstein, vice president of the High Court. “But still, since there are extremists in Jewish society that have done these kinds of terrible things, even if the deterrence is carried out on the assumption that it will influence a small number people, it will still save lives,” he posited.

Elyakim then laid out a hypothetical situation to illustrate the point. “If five attackers in the Jewish society planned five separate attacks and three of them are deterred from doing so because they don’t want to lose their homes, we have achieved something.”

Justice Hendel was also reluctant to accept the apparent discrimination existing between the state’s responses to terrorists of different religions and ethnicities.

“If this is the result for Arabs but not for Jews, we need to ask ourselves whether we are asking the right questions: are there standards? Because unfortunately, we are not dealing with one or two cases, there are more. So why not ask this?”

The state lawyer rejected the notion that the culprits should be treated on an even footing by propounding that the scope of the phenomenon of terrorism remains disparate for Arabs and Jews.

The claim prompted Justice Zvi Zilbertal to ask, “If it’s possible to prevent one murder through preventative action, will they do it only after 20 murderous attacks are be carried out? When we’re talking about human life, it is not the quantity that counts.”

Justice Hendel echoed his sentiment by adding, “If it can prevent five murders, then it is justified. It would be justified if it prevented even one such incident.”

Justice Rubenstein noted that while it is quite possible that home demolition in this particular case may not be warranted, the possibility of its application to other incidents involving Jewish terrorists should not be ruled out.

The state’s attorney responded by saying, “The state has not said that this mechanism could not be implemented with Jews. If a change were to occur, the circumstances would be considered, and a different decision could be reached, if God forbid there would be a Jewish wave of terrorism.”