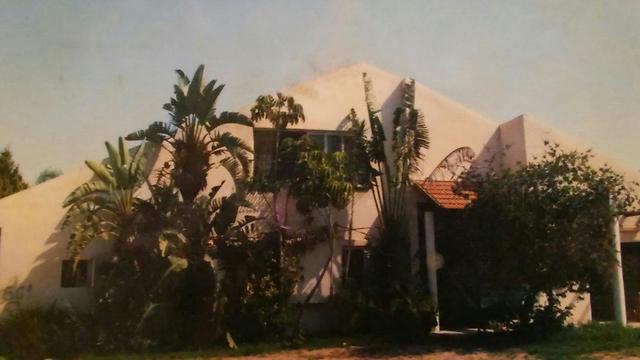

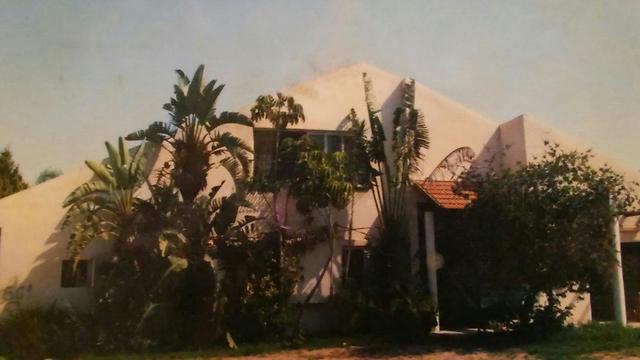

The Shalmon family's caravilla in Amatzia

באדיבות המשפחה

12 years after Gaza disengagement, families still living in ‘caravillas’

Dozens of families evacuated from Gush Katif in the summer of 2005 have yet to receive permanent housing instead of the prefabricated mobile homes that were built as a temporary solution. ‘We have encountered almost every possible bureaucratic barrier,’ one of the evacuees says, calling on the state to ‘conduct a serious self-examination.’

Twelve years have passed since the disengagement from Gaza, and billions of shekels have been invested in the plan that was launched in the summer of 2005. Despite the establishment of two special disengagement administrations, the Gush Katif settlers’ committee says, some 160 families that were evacuated from the settlement bloc are still living in prefabricated mobile homes known as “caravillas.”

“There is still a long way to go, but we can see the horizon,” says Natan Bar, a former Gush Katif resident, who still lives in a caravilla in the community of Amatzia.

Officials at the administration in charge of handling the evictees, which is led by Agriculture Minister Uri Ariel, say there are actually 100 families which are still living in caravillas and most of them are in advanced procedures for a permanent solution.

The families have been pinning their hopes recently on three new permanent communities established especially for the evictees. After many years, the land in Neve Yam is finally being levelled in recent months ahead of the construction of permanent homes for the evacuees, and about 20 families from Kfar Darom have begun building the first homes in a new neighborhood created for them in Moshav Nir Akiva.

The Shalmon family’s old house in Gush Katif, before the disengagement (photo courtesy of the family) (באדיבות המשפחה)

The situation in the community of Amatzia in the Lachish region is a good example of the hardships experienced by many families of evacuees. According to Natan Bar, the trouble began from the very first moment of the community’s construction. “We have encountered almost every possible bureaucratic barrier. Instead of promoting things and understanding that some hurdles must be overcome—so that people who have done nothing wrong would receive their piece of land as fast as possible—almost every single body we faced created some kind of obstruction.”

Bilha Shalmon, another community member, adds: “It hurt us that when we had to be uprooted, things were done without any delays and bureaucracy, and afterwards everything had to be done by the book. Every powerful government worker was able to stop and delay.”

Eliezer Auerbach, the chairman of the Gush Katif residents' committee, points an accusing finger at the state too, warning of similar delays in the outposts of Amona and Migron. “The state doesn’t know how to build communities quickly,” he says. “The regular method takes years. All these years, we have demanded shortcuts in the processes to speed it up. The same thing is going to happen in Migron and Amona.”

Some of the delays in Amatzia had to do with petitions filed by environmental organizations and inspections conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority in the community, but quite a few of the setbacks were the result of simple bureaucracy and a slow-working system. Twelve years are a considerable amount of time for a family: Children are born, join the army, get married—and the cravailla is still there.

One of the main difficulties in living in caravillas is the feeling of transience, but according to Bar, there’s a medicine for that too: “The big problem is that everything always seems temporary. Every year they tell you it’s about to happen, in a year, in two years. It creates frustration and mistrust towards the authorities in all kinds of situations. What helps strengthen the people here is the communal life. Otherwise, I don’t know how people would hold on here.”

Building momentum underway

Recently, the life of the Gush Katif community in Amatzia has taken a turn for the better. In the past six months, the first families have started populating the permanent houses and there is a building momentum in the community.

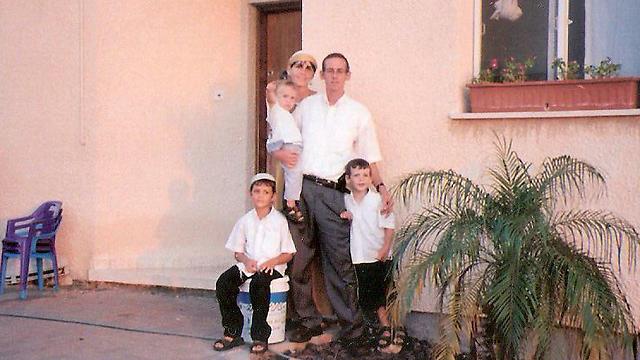

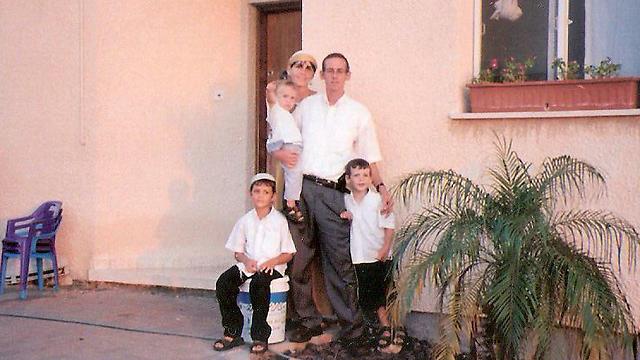

The Bar family today. Communal life helped the families hold on (photo courtesy of the family) (באדיבות המשפחה)

The Bar family outside its home in Gush Katif, before the disengagement (photo courtesy of the family) (באדיבות המשפחה)

Bilha Shalmon entered her new home in Hanukkah. “It’s sort of like reaching a state of tranquility,” she says. “I don’t know if I’ve come full circle. I’m here in a stable house, built out of stone, a house we planned and dreamed of, but Gush Katif is still a place that exists and I believe that one day the people of Israel will return there.”

Despite the difficulties of living in a caravilla for long, Shalmon says her family did everything to make the place feel like a home. “We came here assuming that we would live here for about two years. That was the statement. We said we would put up a curtain and a picture so that we would have a pleasant atmosphere in the house, although it’s only for two years. In the end, these two years were extended to 12 years. On one hand, there was a desire to build the home, and on the other hand, we made sure to lead a normal life in the caravilla that we called home, not to sink into the uncertainty around us.”

About two weeks ago, the community held a cornerstone laying ceremony for the families’ public building, including a synagogue named after Tali Hatuel and her daughters, Gush Katif residents who were murdered in a shooting attack near the Kissufim Crossing. This is another stage in the construction of the permanent community, but the residents are concerned that the money invested by the state in the building won’t be enough for the community’s needs.

“There’s a feeling that the state must conduct a serious self-examination,” says Bar. “I’m not just talking about the level of damages or what people had to do to get them. This whole process of the move and of establishing new communities requires a significant self-examination.”

Nevertheless, in light of the developing construction and the reinforcement of the community, there’s a positive feeling. “We’re definitely seeing the light at the end of the tunnel,” Shalmon concludes.