Pakistan’s only declared Jew hopes to ‘chase away the darkness’

He was tortured, ostracized and kicked out of his home, but refused to give up his persistent struggle to convert to Judaism, a crime punishable by death in his Muslim country. In an exclusive interview, Fishel Benkhald talks about the price he paid for his stubbornness and shares his dream of visiting Israel and opening a kosher restaurant in Karachi. ‘After so many years in the dark,’ he declares, ‘I’m coming out and saying: Look at me, I’m a Jew.’

“My children are young and I don’t want to force religion on them, but I believe it’s important for them to learn about the Jewish holiday customs. When we celebrate a holiday or Shabbat, they’re happy that their father plays with them, and I always let them taste holiday dishes and sweets. They also enjoy listening to me say all the blessings.”

A day after our conversation, however, the holiday preparations were disrupted when his landlord decided to kick Fishel, his wife and their two small children out, after discovering his tenant was Jewish.

“I’m used to packing up and moving homes,” Fishel says. “In the past two months, I’ve already been asked to leave two apartments. The landlords told me I was a target for the Taliban or ISIS, that they didn’t want to take responsibility in case their apartment would be set on fire or they would be harassed for renting it out to a Jew. So now I’m looking for a third apartment. I won’t fold to anyone. If I didn’t give in to my country, I definitely won’t surrender to landlords. I’ll show them this Jew is stubborn.”

Fishel has paid a heavy price for his stubbornness. Not only has he been kicked out of apartments, he has also been socially ostracized and has even experienced violence. Just a few weeks ago, when he tried to open a bank account and stated in the forms that he was Jewish, the bank refused to approve the account. That’s what happens to a guy who is half Jewish and half Muslim and has demanded that his country, Pakistan, recognize him as a Jew, although it is legally impossible for a person registered as a Muslim to convert.

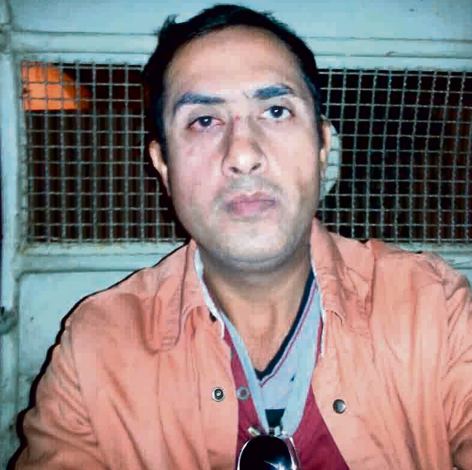

Today, he is the only proclaimed Jew among the 190 million residents of Pakistan, where the passport states: “Valid for all countries of the world except Israel.”

In a first exclusive interview to an Israeli media outlet, Fishel Benkhald talks about his childhood and the difficult battle he waged to explore his mother’s roots. “After so many years in the dark,” he says, “I’m coming out and saying: Look at me, I’m a Jew.”

He was born 30 years ago to a Jewish mother and a Muslim father as Faisal Khalid, the youngest of five children. His father Khaled was born in Lahore and settled down in Karachi, the most populated city in Pakistan. “He came from a religious Muslim family, but those days life was easier and there was no religious coercion in Pakistan, as there is today.”

The father was a mechanic who managed projects for the company he worked for in Tunisia, Morocco and Saudi Arabia. “Because he traveled around the world, he was open-minded. He turned away from Islam and became an atheist.”

His mother, Nasim (“breeze” in Persian), comes from a Jewish family that arrived in Pakistan from the Iranian city of Yazd. “When modern Pakistan was established, my mother’s family had a business in Karachi and they decided to stay. My mother was born here and lived as a Jew, but mostly in great secrecy. There wasn’t much tolerance towards Jews here.”

His parents met in Karachi and married young. “My father didn’t mind that my mother was Jewish. He was a secular who believed in the God of Abraham and didn’t really abide by the laws of Islam. They were married in a Muslim wedding. My mother’s parents were no longer alive and she hardly had any Jewish relatives. They also decided to spare themselves the headache of a mixed wedding and were afraid to expose my mother’s identity. I think they had a symbolic Jewish wedding ceremony secretly, but I’m not sure.”

None of Fishel’s four older siblings was interested in Judaism. Only he, the youngest child who was very attached to his mother, showed an interest in her religion. “I don’t like a religion that preaches out of despair or anger, and from a young age there was a part in me that was less and less attracted to Islam. I quickly found an interest in Judaism.

“My mother used to fast on Yom Kippur, but she didn’t tell anyone. Occasionally, we would make Kiddush and drink grape juice. Friday was a special day for us because of Mother’s anticipation—she really looked forward to the Shabbat meal. My father didn’t take part in the Jewish ceremonies, but he sat at the table and gave my mother the freedom to observe her customs.

“I remember one Passover Seder that ignited my imagination and curiosity: I was following with astonishment the order of the blessings in the Haggadah, which my mother was browsing through. Mother said we shouldn’t sing too loud, and of course we didn’t put the candles on the window so the neighbors wouldn’t see them. She told us the story of how the Jews went from slavery to freedom, and she baked matzot and let us taste them.”

And you weren’t allowed to talk about it with your friends.

“Yeah, my parents forbade me to discuss religion with friends, and certainly not the Jews’ customs. We didn’t fast during the Ramadan, but Father forbade me to eat outside the house so the neighbors wouldn’t know we weren’t fasting.

“We definitely experienced anti-Semitism in Pakistan: People would curse the Jews and say they prepare matzah from children’s blood, kill babies and hold satanic ceremonies. Only when I grew up, I shared some of our Jewish customs with a few good friends. When other children found out I was observing non-Muslim commandments, they beat me up. They said to me, ‘You kill Muslims.’ Luckily, I was a strong boy and at some stage they were unable to hit me anymore, because I would hit them back.”

Secrets under the pillow

His mother died of breast cancer when he was 10. “She was buried in the Muslim cemetery, because she had no Jewish relatives left,” he says.

Fishel and his siblings travelled to Saudi Arabia with their father. Four years later, his father died of cancer as well. He remained with his four siblings, who pulled away from him the more he showed an interest in Judaism.

At the age of 16, he told one of his friends about his Jewish roots, and the friend revealed to him that his father was Christian. “He took me to visit a friend of his in a rich suburb of Karachi, and that’s how I met Samuel, a Pakistani Jew who had concealed his religion throughout the years. Samuel gave me a few books and booklets in English about the Jewish mitzvot. I hid the books under my pillow, so no one would see them.”

He read the books in hiding and learned about Shabbat and kashrut through them. “I was like an empty jug, slowly filling up with water. I felt my huge spiritual thirst to learn more about Judaism. When I started working, I would take days off on major Jewish holidays, so as not to desecrate them. I didn’t tell anyone the reason of course, but I began conducting social experiments: I would go to cafés, sit next to people, and we would start talking about religion. And then I would ask them, as if incidentally, what they thought about Jews.

“The reactions were usually harsh: ‘Muslims can’t be friends with Jews,’ ‘Jews are Satan.’ Views based on lack of knowledge, because there are no Jews in Pakistan, at least no declared Jews, so how would people get to know them and learn about them? But to be fair, there were some who said, ‘Does it really matter? We’re all sons of Abraham.’”

But one time, when he took a further step forward, he almost paid with his freedom and life. He began discussing religious issues with a friend in an online chat. Then he told him he was Jewish. The two decided to meet for coffee in a crowded place.

“We talked about Pakistan and about Israel. I explained to my friend that only a Muslim could be prime minister under Pakistani law, whereas there was no such law in Israel. I added, however, that Israel had the right to maintain a Jewish majority. He didn’t like what I said, called his friends, and the discussion heated up. They assaulted me, knocked me down to the ground and started kicking me in the stomach and in the face. Then they called the police and told them I was an Israeli Mossad agent who was speaking out against Pakistan and against Islam. ‘He’s a Zionist criminal,’ they screamed.

“The police arrested me. I was tied to a chair for 18 hours, blindfolded. They interrogated me and hit me. They asked if I were a Mossad agent and how was I connected to Israel. I said I wasn’t a Mossad agent, but a Zionist who believed in the State of Israel’s legitimacy. I told them that like Pakistan, Israel had received independence from Great Britain, and I asked the police officers what was the difference. They showed me different torture devices and threatened to torture me until I took back what I said. I said to them, ‘Do what you want, but I’ll keep voicing my opinion.’

"Luckily, shortly before I was arrested, I took a picture of my bruised face and posted on Twitter that I had been beaten up for being Jewish. American journalists saw the tweet and contacted the police in Pakistan. After hours of interrogation, I was released.”

He completed his studies in Saudi Arabia and returned to Pakistan, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in computer engineering and mechanical engineering.

“My uncle took the entire contents of my parents’ house, including a menorah and candlesticks that had belonged to my mother. I had trouble accepting that her death would mark the end of our family’s Jewish roots. After all, there is no Jewish community or synagogue in Pakistan to offer you support and a place to pray. Even the cemetery in Karachi has been deserted for many years, without anyone visiting or coming there to say Kaddish.”

A touch of Yiddish

Pakistan’s Jewish community was small and quiet. Some 2,500 Jews moved to Pakistan from Iran or India from the mid-19th century to the mid-20th century. Most lived in Karachi. The Magain Shalome Synagogue was built alongside other Jewish community institutions.

In 1947, the Brits left Pakistan and the country gained independence. A year later, upon the State of Israel’s declaration of independence, Pakistan adopted a clear and strict anti-Israel policy. Many of the country’s Jews immigrated to Israel. Some of the Jews who remained in Pakistan converted, married Muslims and assimilated. Few maintained their Jewishness in utmost discretion, but chose to declare themselves Muslim in the census registrations, out of fear of being harassed by the government.

In 1988, the synagogue was torched and destroyed, and a pedestrian mall was built in its place. It was a symbolic act, marking the end of Pakistan’s Jewish community. The last Jews of Karachi saw the synagogue go up in flames and became, at least outwardly, Muslim.

Pakistan has reported in recent years that there are 900 citizens registered as Jews in the census registration, but that figure includes citizens who were Jews in the past, or at least declared they were Jewish, and no longer observe Jewish mitzvot. Many of them are elderly people who decided to stay in Pakistan while their relatives immigrated to India or to Israel. Former members of Pakistan’s Jewish community built a new synagogue in Lod and named it Magen Shalom after the Karachi community’s old synagogue.

The religious radicalization process that has been taking place throughout Pakistan in recent years, and the support of many of its citizens for organizations like al-Qaeda or the Islamic State, have turned the country into a dangerous place for Jews.

In Pakistan, which upholds Sharia law, a Muslim person cannot convert. So imagine the amazement of the state’s authorities when a young man showed up and demanded to be recognized as a Jew.

“Five years ago, I reached the conclusion I wanted to live as a Jew,” Fishel says. “I believe in freedom of religion, and I wanted to contribute to the fight for tolerance in my country. I had enough of living in the 21st century but not being able to be who I am.”

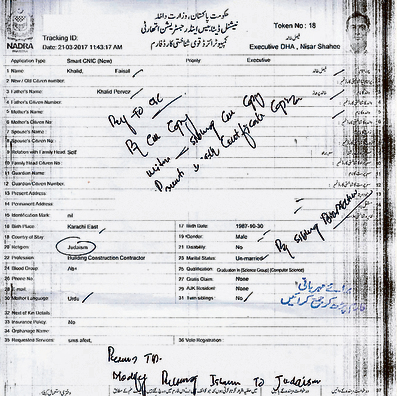

He started sending letters to the Pakistani Interior Ministry, asking to change his religion in official documents. He even changed his name from Faisal to Fishel, “because I wanted a Jewish name that would be similar to my original name, with a touch of Yiddish.” He decided to keep his father’s surname, Benkhald.

The Interior Ministry didn’t like his initiative and ignored it. “When I called them, they mocked me on the phone and said that since I was born Muslim, I couldn’t change my religion. In late 2014, I went to the census registration office and asked them to amend the religion registration clause. They were shocked and explained I could get the death penalty. I said I was a law-abiding citizen, but that laws were something that changed according to circumstances. I explained that my mother was Jewish and that I believed I was Jewish too. They called the security officers and threw me out of the building.”

At the same time, Fishel also contacted the United States consul in Karachi and told him about his struggle. Rabbi David Sparstein, who was appointed by former US President Barack Obama as the US ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, visited Karachi two years ago and Fishel was invited to meet him. “He was courteous and showed an interest in my story. At the end of the meeting, he agreed I should be entitled to freedom of religion in Pakistan. I was later invited to two additional meetings with a representative of the US State Department who was visiting Karachi. At the same time, my story was published in media outlets in the US and many American Jews offered to help me.

“I kept in touch with the census registration office, until one day they told me to send an email with my request to the main office in Islamabad. For the first time in Pakistan’s history, they actually agreed to discuss a person’s request to convert to a different religion. After months of foot-dragging, with each office trying to pin responsibility on the other office, I received the approval: Pakistan’s Interior Ministry had decided to change my religion in its registration. I’m no longer a Muslim, I’m a Jew.”

Last March, Fishel officially became Jewish. He is not only the first person in Pakistan to receive permission to “convert” from Islam to Judaism, he is also the first person in the country to register as a Jew in the past few decades. Fishel received a new identity card, but the authorities removed the religion clause from it altogether. In recent months, he has been repeatedly checking to see whether his religion was changed in the office registrations as well, “to make sure they’re not lying.”

The letter informing him of the long-awaited approval was sent to his house. “I cried, of course I did,” he says, the excitement evident in his voice. “I felt extremely proud of my struggle and of a similar struggle waged by many people, in Pakistan and in other places, for freedom of religion.

“On a personal level, I remembered my mother, may she rest in peace. I felt I had fixed things, that I had driven away the fear she wrapped herself in her entire life, when she was forced to conceal her Jewishness. I said to her out loud, ‘Look, Mother, you don’t have to be afraid anymore.’ Just like people come out of the closet in the LGBT community, I felt like I had come out of the Jewish closet.

“Now I’m standing up and saying out loud, ‘I am a Jew. I will no longer be afraid, I will not hide, I will not be a victim of violence.’ I insisted and I fought for a principle I believe in, for me, for my mother, for the Jews who were killed by the Nazis, and for any Jew anywhere in the world who is forced to keep his head down. Yes, even for the Jews of Pakistan, who are hiding and living under a false identity. I wanted to say, ‘I opened the door for you, come out.’ I hope some of them will follow in my footsteps and rediscover their roots.

“Perhaps the small candle I have lit will manage to chase away the darkness, and perhaps one day we’ll get to light Shabbat candles—not inside the house, but on the window sill.”

Dreaming of a bar mitzvah

Now, Fishel wants to revive Pakistan’s Jewish community, build a new synagogue and rebuild Karachi’s cemetery, which he visits occasionally to connect—through the dead—to his new Jewish life.

He is married and has two small children, who he is very protective of, "so they won’t suffer as I suffered as a child." They make Kiddush and celebrate holidays, and Fishel took his children to visit the cemetery when he was photographed for this story. He has submitted a request to register his children as Jews too, but the chances his request will be granted are small. “It will be hard for me to prove they’re Jewish, but I’ll fight for it. I want my children to grow up and marry Jewish women, and together we’ll reestablish the Jewish community in Pakistan.”

He’s afraid to expose his wife. “My choice to revive my Jewish roots isn’t her choice. She respects me and my religion. I don’t want her to get hurt.”

The interview was held over an entire month through Skype, which turned out to be a particularly complicated task in Pakistan: There were repeated power outages in his city and the internet access was disabled too. Conversations were cut off and resumed only days later, when internet access was restored. “I’m really sorry. There’s nothing I can do about it. That’s just the way it is in Pakistan,” he apologized again and again. “I wish I could invite you to visit me in Karachi,” he added.

He always started off our conversations by greeting me with “shalom” (hello) and concluded them with “toda raba” (thank you very much) in Hebrew. Occasionally, he would ask me about Jerusalem and about Tel Aviv, in a bid to slightly satisfy his curiosity towards the state he had never visited.

Now, Fishel is planning a new battle against the authorities, to make them recognize the Karachi Jewish cemeteray as a preservation site so it won’t end up like the destroyed synagogue.

Like a person who has rediscovered himself, Fishel is highly enthusiastic and has many new ideas. He wants to study Judaism and open a kosher restaurant in Karachi. “I want to change people’s prejudice through their stomach. If they learn about the Iranian or Moroccan Jews’ food, they won’t hate Jews.”

He plans to submit another request the authorities probably won’t like either: To visit Israel. “A Muslim can issue a pilgrim’s visa to Mecca, so why can’t Israel recognize me and allow me to observe the pilgrimage mitzvah? I dream of visiting the Western Wall, placing a note, praying to the God of Abraham, Moses and my mother. I also dream of celebrating the bar mitzvah I never celebrated.”

Why don’t you consider making aliyah?

“I’m not allowed to say I want to immigrate to Israel, because they’ll say I’m a Mossad agent and arrest me. My Pakistani passport explicitly states I am not allowed to visit Israel, but I do hope the State of Israel would perhaps signal Pakistan to allow me to visit the country of my forefathers.”

In light of the reactions you have received, don’t you fear for your life?

“Not really. I go outside and look around to see no one’s following me, but there isn’t much I can do beyond that. I have two good friends who know I’m Jewish and accept me. I’m accepted at the company I work for too, after proving to be a good employee. The company owner is a Shiite Muslim and the Shiites suffer from discrimination here too, so he understands the situation I’m in.

“On the other hand, ever since my picture was published, and I was marked as a ‘Jewish traitor,’ many of my former friends and neighbors have chosen to stay away from me. My brother gave an interview to a local news agency and said he didn’t share my struggle and wasn’t Jewish. My siblings have cut ties with me. I understand them. They’re afraid of facing problems. Not everyone can be the person he is. But I’m not going to give up.”