Waltz with Bashar

In late 2007, less than a month after the Israeli attack, Ynet correspondent Ron Ben-Yishai traveled to Syria and reached mere hundreds of meters away from the destroyed nuclear reactor. A decade later, he recounts the cover story he used, the tour of the hostile country and his conversations with the Syrian citizens.

A Syrian border guard took my (non-Israeli) passport and flipped through its pages several times. "Where's the visa?" he asked. "I don't have a visa," I said. "A friend told me you could get a visa to Syria at the border." This was the truth, but not the entire truth. There was no point in telling this sleepy Syrian policeman that the Syrian Consulate in Istanbul has refused to give me a visa and rejected me again and again. The secretary hinted to me that my Jewish name aroused the consul's suspicions. At the advice of a friend, a Turkish journalist, I decided to try my luck at one of the small border crosses between Turkey and Syria. Perhaps there my name wouldn't raise suspicions. (Published in Yedioth Ahronoth on September 28, 2007, some three weeks after the strike on the reactor)

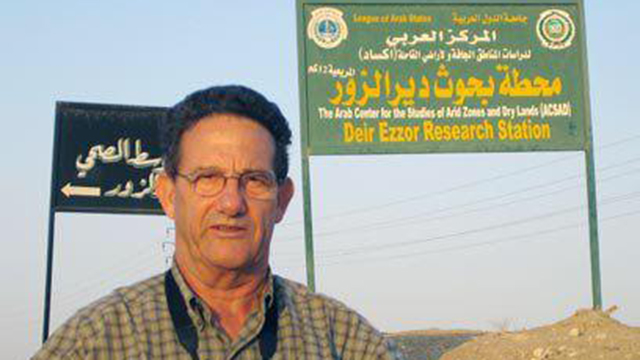

Two weeks after the nuclear reactor was bombed, I entered Syria through a remote crossing in a place called Kilis, on the border between Turkey and Syria, not far from Aleppo. I was aided by a clothes merchant who hoped to smuggle through me some of his profits when I returned to Turkey. I introduced myself as an innocent South American tourist, and when I was questioned, I explained that I've been teaching geography my entire life, I worked in geography, and now I wanted to see the areas I was specializing in.

It was a late hour of the night and the soldiers at the border crossing called the officer on duty at the Foreign Ministry in Damascus, who authorized my entry. They checked how much money I had, and when they were satisfied I had enough to leave the country, they said "Welcome."

At the time, we knew very little about the military operation. We knew - even though we couldn't report it - that the Air Force bombed a nuclear facility, but we didn't know it was a reactor. As far as I knew, it could've also been an enrichment facility or a facility to reprocess nuclear fuel. However, I knew Deir ez-Zor, where I was going, is an area filled with phosphates that could be used in the production of uranium. Saddam Hussein, for example, produced uranium several dozens of kilometers south of that area for his own nuclear program. I believe the same applied to Assad.

I wanted to get to the facility that was bombed, and I heard from different people that the airstrike was southeast of Deir ez-Zor. But it's not a simple trip that can be made in a taxi or a rented car. It's far more complicated. To establish credibility for my story, I traveled around Syria for a little bit beforehand. It's not unusual, by the way. I believe there were quite a few Israelis who traveled in Syria with foreign passports.I toured Aleppo for three days. Nowadays, the city is in ruins, but at the time was at its full glory. I then took Syria's main highway along the coastline to Tartus, and from there to Hama, and then to Homs and Damascus. Along the way I was talking to the driver and other people I met about the attack. Some of them didn't even know about the incident, and some told me "It's nothing, just bombs going off in the desert." On the way, we passed by military bases, and I was interested in seeing whether there was agitation or militant sentiments there, manifesting for example in unusual tests. But there wasn't. Syria was very calm.

I arrived to Damascus on the eve of Yom Kippur, and I spent the fast at the French synagogue in the city. I told them I was a geographer who documents different nations' customs, and that is why I filmed the closing prayer. It appeared alright to them. There was a Syrian regime guard at the synagogue from the Mukhabarat (Air Force Intelligence Directorate) there, but I bribed him and everything went without a hitch.

'We heard some explosions'

I couldn't find a trace, not in Damascus nor in other places I toured, of the winds of war that were blowing in Israel with such force. The Syrians I spoke to, from the bazaar merchants to the government bureaucrat who sat next to me at the table during a holiday meal at a hotel in Damascus, all claim that there will be no war with Israel. “Syria doesn’t want war and won’t launch a war in the foreseeable future,” the bureaucrat said decisively. “But we want the Golan that Israel conquered from us. We have patience. In the end, we’ll get it back. Threats are an effective pressure measure, war is something else entirely. I think the Israelis are the ones who want war, and that is why they’re doing provocations against us non-stop.” (Published in Yedioth Ahronoth on September 28, 2007, some three weeks after the strike on the reactor)

I stayed at Le Meridien Damascus during the month of Ramadan. In the evening, senior Syrian bureaucrats would come to the hotel for iftar, the meal to break the fast. One of them said he was working in the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Trade, and even though I couldn’t ask them directly, I could see there was no particular agitation in the wake of the Israeli strike.

So I rented a Volkswagen Touareg whose owner was also the driver, and with him I traveled to the place for which I came. I couldn’t go directly to Deir ez-Zor, but on the way there from Damascus there are enough sites to visit. We went to see the archeological finds in Palmyra, and from there I told the driver I wanted to get to the Euphrates River to see the Assad Dam. Traveling north along the Euphrates is exactly the route that would lead me to Deir ez-Zor and to the area where, according to reports, the strike was carried out. To the Syrian driver, this seemed a perfectly reasonable route.

On the way, I started inquiring – gently – about the strike. I was sitting at a café and asked someone innocently: “Isn’t it dangerous to travel around here? I was told there was an Israeli strike.” He replied that no, because there was no attack at all. “We heard some explosions, we heard some planes in the night, but that’s normal here.” Others I asked believed the TV report from the Syrian regime, according to which Israeli planes dropped some pieces of metal in the desert.

I spent the night in Deir ez-Zor, but I couldn’t appear to be overeager to get to the area of the airstrike - I had to continue playing the tourist. We went northeast until we reached the Euphrates River. The road stretched along the river, and on its eastern bank were oil fields and industrial complexes.

At the time, I had no idea where the reactor had stood. Today, I know it’s not far from a small, isolated village called al-Kubar. But at the time, we simply got to a Syrian army roadblock. The first thing the Syrian officer at the roadblock did was snatch my video camera away. I realized I was at the right place.

800 meters from the reactor

When I tried to talk to students at the department of economics at the university, I was suddenly approached by two young men in civilian clothes who asked me what I wanted to know. When they were satisfied with my answers, they simply asked me to leave the university campus. I was still able to speak to one student who had an original opinion about Israel. “I ask you,” she told me, “how is my government different to the Israeli government? Our government treats us just as bad as the Israelis treat the Palestinians.” She didn’t have time to finish her thought when the Mukhabarat showed up and demanded that I leave the place. This time, I did as they asked. (Published in Yedioth Ahronoth on September 28, 2007, some three weeks after the strike on the reactor)

I got out of the car, looked around, and saw pipes going into the Euphrates. The facility was built near the river so water could be pumped from it to cool the reactor.

Since I’m used to this kind of situations, I wasn’t panicked and didn’t show any signs of stress when dealing with the Syrian officer. After all, the camera had a new and empty tape. I argued with the Syrian officer a little bit, as did my driver, who was paid handsomely and therefore argued on my behalf. But the officer insisted: You can’t film, and you can’t travel further.

While we were arguing, I saw through a crevice between the hills, where the pipes were, something that looked like a quarry, some 800 meters from me. I could see trucks coming and going, and Syrian soldiers moving in the area.

In hindsight I know that because the Syrians were worried about inspections of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which would lead them to find out what the facility really was, they simply scraped all of the dirt from there to collect any remnants of radioactive materials.

Eventually, I told the officer I only wanted to go to the Assad Dam, so he returned my camera to me - without the tape - and let me go.

From the Assad Dam I returned to Damascus, without stopping in Aleppo so the clothes merchant won’t find me. Later, I got all the way to Quneitra, but I couldn’t enter it because a special permit is required for that. I did stand at its gates, from where I could see the IDF outposts across the border and Mount Hermon.

I told myself, “Enough. It’s been ten days, you’ve done your job.” I asked the driver to take me to the Damascus Airport, and from there I flew out of Syria.