Israeli ambassador's farewell to India

Ambassador Danny Carmon was born into diplomacy, lost his wife and was wounded in the Buenos Aires terror attack, but got right back on the horse, representing Israel around the world. We joined Carmon on his goodbye tour of the Indian subcontinent, hearing about Israeli backpackers in trouble, business ties between Israel and India and the cultural dissonance.

The Mumbai slums are both chaotic and wonderful. An endless number of vehicles, motorbikes and rickshaws coming from the left and the right, almost colliding, honking their horns, accelerating, hitting their horns again. The sidewalk is crammed with people walking in opposite directions, and others are hard at work: Three people fix a pothole in the road, street vendors sell food, a man carries a huge metal object on his back. On the edge of the busy road, by piles of garbage, a rusting amusement ride draws young children. In the middle of traffic, a police officer stands and blows her whistle while waving her arms, but no one takes notice.

Huge bridges and towering new buildings with Netflix and Uber commercials reside alongside grimy, filthy, soot-covered buildings, with rows of laundry covering their fronts. Under and on top of these building sit countless slumsy shacks. The two—the extreme luxuries and abject poverty—reside together in an impossible mess that has no rhyme or reason. The crowded, smelly and humid streets are both fascinating and unbearable at the same time.

And then, it painfully dawns on you: right near the Israeli consulate, I detect a traffic island that people live on. A young woman with a baby in her arms reaches out to another baby, while the contents of their shack is exposed to all, at the heart of the road.

India will hit you sooner or later. One of the consulate workers told me he had only realized where was when, soon after landing, a man pulled his pants down right in front of him to do his business. The Israeli Consul in Bangalore, Dana Koresh, said that for her it was the child beggars: “A mother holding a baby and begging, or toddlers that drove cart-wheels for ten rupees.”

Maya Kadosh, the ambassador’s stand-in, remembered how when she arrived, she stared out the window for hours: “The drivers, vendors, beggars, the people that live out there. Everything happens on the street. It’s like an Indian film.”

I arrived in India to accompany Israeli Ambassador Danny Carmon’s farewell tour and got a peek into Indian politics, the odd life of ambassadors in such a foreign land and India’s complicated relationship with Israel.

How can we begin to understand a subcontinent of 1.3 billion inhabitants, with so many traditions and cultures, sights and smells, languages and contradictions; a country that suffers natural disasters, extreme climate and unbearable pollution?

The face of Israel

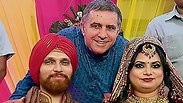

It was a stuffy long day when we arrived in Punjab and sat surrounded by a Sikh minister—wearing all white and a pink Turban—and his advisors. He was telling Carmon about Punjab’s serious water issues and their desire to acquire Israeli technology to assist them.

We continued to the Haryana annual mango festival, where local journalists bombarded Carmon with questions. He then gave a speech to farmers and finished off by giving out awards to the mango quiz champions and to a boy who devoured nine mangoes in one minute.

After lunch and a tour in a local farm, we continued to one of 22 centers for agricultural excellency under joint Israeli-Indian management, where local farmers get advice on using Israeli technology for different crops.

It was getting late when a farmer asked Carmon if he would look at his zucchini patch. Delhi was three hours away, and it was a long, long day. “It would only take two minutes,” Carmon told his tired party and went to see the patch.

That’s what it’s like to be an ambassador. You are the face of Israel, and you can’t let an excited farmer down.

Carmon, 67, a father of six, has been the face of Israel since he was born. His father Menahem Carmon was an ambassador and diplomat in Czechoslovakia, France, Turkey, Senegal, the Ivory Coast and New York. His first memory is listening to a marsh playing on huge loudspeakers in the streets of communist Prague. He then reminisces about how he told friends about Israel when he was a first grader in France: “You are born a PR child, and that’s true to all diplomatss children,” he said.

The son of the diplomat became a diplomat himself. Washington, Argentina, New York and finally New Delhi. Indians would see it as destiny, but Carmon doesn’t believe in such things. During his time in Argentina, in March 1992, a suicide bomber blew up a car bomb by the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, killing 29, four of which were Israelis—including Carmon’s wife Eliora. Carmon was wounded in the attack, and temporarily lost his sight.

“I remember the moment of the explosion. I remember the silence after the boom. I remember myself lying on the floor of a van transporting me to the hospital and the bumps on the way. After that, I lost consciousness,” he recalls.

After waking up, he insisted on telling his five children himself that their mother was gone. “They brought them to me at the hospital bed,” he recalls. “After a month of grieving, I asked to return to Argentina. It was important to me to show the kids that life goes on, to help rebuild the embassy, to support the Argentinians at the embassy, some of whom bear the scars to this day.”

After Argentina, he returned to Israel, where for the next eight years he raised his five children on his own. Later he met Ditza Froim, an employee at the Foreign Affairs Ministry. “She could have been the ambassador herself, but gave it up for me,” says Carmon.

He left for India with Ditza, who is concluding her mission as an envoy in Delhi, and with their 14-year-old daughter Emma, leaving his five adult children in Israel.

“There’s a sentence I often repeat: ‘this is the story of our lives,’” he says. “Being away from my own parents was just as difficult as being away from nt children, especially as my parents aged and needed my support. Before my parents passed away, my father uttered a terrible sentence: 'You are going abroad, and that will be difficult for me, but I did the same to my parents.' My mother passed away in 2005, and my father passed away three months later. But that is the 'deal.' I knew what I was getting into, because I experienced this as a child. Every time my parents went abroad, my father kissed the Mezuzah, as if to say: I’m leaving, and I will come back. Indeed, the story of our lives.”

Now, after a lifetime devoted to international missions in the service of his country, Carmon is retiring. He is likely to continue being on the move, this time in support of of Ditza, who may become ambassador. And he doesn’t believe in destiny.

Nikki’s tuk-tuk

The tuk-tuk driver is named Nikki. Just Nikki. He insists he has no surname. “My friend,” he says, “poor people don’t have such things. They don't celebrate either. Not birthdays, not holidays.”

In contrast to other tuk-tuk drivers in Delhi, Nikki navigates through the narrow garbage-strewn alleys with care. He drives tourists, many of them Israeli, as part of his work with the Chabad House at the “Main Bazaar,” the Israeli backpackers’ hub.

Driving a tuk-tuk is new to him. He used to work as a shoe-shiner. “I used to live on the street, but now I’m too old for that job. So I work and live on the tuk-tuk,” he says.

Now you have a place to sleep, that’s good.

“No, now I have a tuk-tuk to worry about. It costs me 500 rupees per day.”

I don’t understand.

“You have a house to take care of, a job to maintain. I don’t have such worries, except the tuk-tuk.”

It’s hard not to consider what he is saying. “You, in the West, are stressed, because you think you have control over your situation,” says an Indian businessman during a meeting at a hotel in Pune, “in India, people roll with their destiny. Man is part of nature. The downside is that it is a passive society. The Israelis, by contrast, invest every moment in innovation, in improvement. That is a spirit that’s lacking here.”

“Poverty is difficult to grasp. Once you’re in, it’s not certain you will want to get out,” an Indian minister will later say. Another official will tell us of the slum dwellers who received houses but refused to leave the slums, “because that is their place, their social standing.”

“In the past, the poor of India would say: ‘this is our destiny, and we accept it,’ but today people are more informed, and they don't want to stay behind,” says Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, CEO of an Indian Biotechnology empire, one of the wealthiest and most influential women in the world.

We met the Indian billionaire at a café in Bangalore. Mazumdar-Shaw, 65, recounts her personal story: how 40 years ago she founded a business with dim prospects. “I wanted to get credit at the bank, but I was a woman, in India, young and inexperienced. They said: ‘How can we give you a loan?’ Others said: ‘How could we work for you?’ Even women did not want to work with me. I didn’t know how to reach markets. It was a journey full of hurdles.”

Today, India has moved on, she says, but that is still far from being enough. “Every child in India needs to learn technology to have opportunities. We’re afraid of progress, but every time a new technology emerges, it generates creativity. We don’t remember phone numbers nowadays. Does that mean something in us has gone wrong? Not at all. We simply use those resources for other endeavors.”

The subcontinent, of which 80 percent of the inhabitants are agricultural workers, is looking to the West. “There are a billion cellphones in India, half of them smartphones,” says an official in India’s cyber agency. He talks of the locals’ difficulty in discerning fact from fiction on the web—a phenomenon that has led to lynchings, which claimed the lives of dozens of victims.

India is busy these days with the nation-wide project of toilet installation. The country is stirred by the film “Toilet,” a love-story of a woman who leaves her lover because there are no toilets in his house. The woman refuses to do her business in the fields, and forces him to steal a chemical toilet.

India is determined to clean out even the holy river Ganges, which is currently polluted by sewage and burnt bodies. “Eighty percent of the Ganges will be clean by March 2019,” states Nitin Gadkari, the minister in charge of water resources and the clean-up project.

We met at the powerful politician’s office. I asked about Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Ramallah, and his statement that Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat was a “great leader.” Gadkari admits he did not like that statement. “Israel is a natural ally,” he says, “the ties are good and long-term.”

Carmon would later tell him that “the countries’ cooperation in the field of water could be the next big thing,” and invite him to Israel.

“I will come,” Gadkari replies, “I have friends in Israel. Reena Pushkarna (founder of Tandouri), she is like a sister.”

Lost in a snowstorm

In the maze-like slum, with its patched-up structures, operates Dhobi Ghat, the largest laundry company in Mumbai. Two-thousand workers live in this laundry ‘town,’ cleaning the clothes of the millions outside.

Bali, a man in his 60s, his right arm dangling from his thin frame, leads me through the water channels and the stone structures of Dhobi Ghat. Monsoon rains splatter from above, and thick smoke obscures our field of vision.

“Sprite-sprite, housework,” Bali points proudly to the channel where workers are washing clothing, and near it a terribly narrow stone building where a family dwells. “Sprite-Sprite, housework,” he hurries to the next water channel, pointing again to what in the eyes of a foreigner would look like a horrible laborers' colony. There are barefooted children next to us, and an old man crouching in an awkward position on the wet earth. Is he alive? We don't stop to check. After all, there are millions here lying in the streets.

The disparity between the value of human life in India to what we’re accustomed to in the West is unfathomable. In the same day several natural disasters befall India: a family of 11 died in a fire, dozens plunged to their deaths in a bus accident. But India is not shaken.

Ambassador Carmon recalls a meeting with an Indian official in which he wanted to express his condolences on the death of 20 Indian soldiers on the border with Myanmar. “It took him a few moments to understand what I wanted,” he recalls.

Meanwhile, at the Israeli embassy in Delhi, consul Eli Sneh receives reports of two Israelis caught in a snowstorm while on a trek. “They’re reporting that stones are falling on them from the sky and they want aerial evacuation,” he points to their location on a map. “It’s not a laughing matter. We can’t call the Indian Army into action only to find an Israeli high on drugs.”

Before he gets a chance to manage the situation, he receives a report that the two have been rescued with horses. Later he will deal with an Israeli traveler who attacked two Indian policemen. And after that, a quarrel ‘starring’ several young Israelis.

He is 56, and throughout his 34 years in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he has been dispatched to Romania, Hungary, Portugal and Switzerland. Now he is in Delhi. He lives in India alone, he is divorced, and has two adult children living in Israel. Aside from the routine bureaucratic work, he’s the man who doesn’t sleep when young Israeli travelers in India—as many as 80,000 every year—get in trouble.

“And it always happens on weekends, in the middle of the night, or on holidays,” he says, and recalls an Israeli who ‘flipped out’ and thought the Mossad was after him, or that guy who got altitude sickness in the middle of a trek in Kashmir.

“You know Israelis,” he says, “they go travelling thinking ‘I’ve been through Arafat and Hezbollah, this is nothing.’ That’s how the most devastating stories happen. The weirdest stories, people who take mushrooms, young people who lose their sense of time. Many who lose touch with reality, at least three cases per week. They go on treks in places where there’s no communication, they don’t notify their parents. And the parents? If their child doesn’t call for one hour, they go straight to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I treat them like my own children.”

Recently, he had to handle a lethal car accident—one Israeli dead and four injured. The group was on their way to Leh, ten hours on the road. At some point, everybody fell asleep, including the Indian driver. Sneh describes how at a late hour he drove to find an area with good reception so he could manage the rescue mission by phone, and how at dawn he flew to the site of the accident.

All the while he had to keep the families apprised. “I didn’t sleep for 40 hours,” he tells me. “One of the injured was transported by ambulance for 7 hours to Chandighar, the other three were evacuated by military helicopter. In the helicopter, they screamed in pain. One of them said: 'I want morphine.' I told him: 'you already got two.' Everybody had to undergo surgery. It was hell to get them back to Israel. And in the middle of all of that, another event started, an Israeli on a bike that crashed into a bus and died.”

High-Tech and Amba

“Bangalore is India's Garden of Eden,” announced Bhaskar Bakthavatsalu, the managing director at the Israeli cyber security company Checkpoint in India. Bakthavatsalu surveys the city outside his glass window. “Comfortable weather, not many earthquakes. When people retire, they come here.”

Bangalore is the capital of high-tech, the Silicone Valley of the subcontinent. It’s green, well-kept, it doesn’t look like India. “Everywhere else, India looks different,” Bhaskar says, as if reading my mind. “The landscape changes every 10 kilometers, the language changes, the colors of the faces change, the taste of the water. India has deserts, valleys, tropical forests, oceans. Our roots are what connect this whole country. Look what India has given humanity: the Buddha, Vipassanā, the number zero, Kama Sutra. We taught the world how to have sex. Unfortunately, we have less of it nowadays.”

Seeing the enormous potential, Israel opened up a consulate in Bangalore, headed by Dana Koresh. “The consulate’s mandate is economic,” she explains on the way to a meeting with the B-PAC team, a local organization that encourages political leadership.

India, which over its history has preferred its relations with Arab nations and Iran, treats us differently today: security, high-tech, agriculture, water desalination. And unlike the past, the relationship is now out in the open. “I have 12 ministers on speed dial, and they can call me too,” says Carmon.

“Israel is well-respected in India,” he continues. “They tell us: ‘just come!’ But it won’t work if we say ‘Hello, we’re Israelis and we’ll tell you how to do agriculture' or 'we’ll save India.' Who are we to save India? Hundreds of years before we developed our sophisticated agriculture, the Indians were growing hundreds of strains of mango and making Amba. It is an enormous country with traditions and cultures, a nuclear power that launches missiles to outer space. The rule is to approach with humility.”

Do India’s relations with Israel affect its relations with Arab nations?

“It’s not a zero-sum game. The Berlin Wall has fallen, the Cold War has ended, the Middle East has changed. The days when it was thought that if India befriends Israel, the Arab world would be offended, are over.”

Judging by India’s votes at the UN, it doesn’t look like they’re with us.

“It’s a subject that has always divided us, India has always voted with the other side. But there has been some change. We don’t agree with India about everything, but the dialogue is quite open.”

Israeli businesspeople who want to get their foot into this huge market find the Indian reality to be difficult. Many times, the Indians say "yes," but nothing comes of it. “Israeli businesspeople come out of meetings certain that they’re on their way to huge projects, and then the person they were talking to vanishes,” says Koresh.

“When an Indian says 'yes,' he sometimes means to say: ‘even if it's not possible right now, we’ll do our best,’" Bhaskar explains. “I tell my Israeli friends: First of all, you need patience. Second, if you want to only do business, you might succeed and you might fail. But if you come to India for some time, get to know your partner intimately, get to know their families, go out for drinks together, then nothing will stop you. That’s the culture.”

Wanted: Milkman

“Nothing here is taken for granted, not even the sky,” says Maya Kadosh, the acting ambassador. She is 42, and she dragged a husband and three kids with her to Delhi, after more comfortable missions in Singapore, Huston and Los Angeles. “Because of the heavy pollution, you don’t see the sky for months. The psychological effect is devastating,” she explains, “or the extreme heat of over 50 degrees Celsius, or a monsoon that causes floods and brings diseases. And the diseases here are extreme, you don’t just get indigestion.”

It is a difficult place, certainly for Israeli envoys, who stay in the country under heavy security ever explosives were planted on one of the embassy cars in 2012.

In many places the infrastructure is in poor condition. During a city tour of Mumbai, a resident tells us that many of the apartment buildings only get two hours of running water a day. It’s hard to know if he says this in frustration or pride. The millions who live in the slums do not have even that.

One of the embassy workers in Delhi tells of an envoy who had come from Israel, rented an amazing apartment, and only after having moved realized it is not connected to running water. “Everything here is ‘almost,’” she says.

Consul Koresh had a problem with her phone for a few days. She sent it to be fixed and got it back bound together with duct-tape. So she sent it back to be fixed, again and again. “I said to myself: Dana, breathe, this is India.”

Yaakov Finkelstein, the consul in Mumbai, recalls how a tiny construction job took days on end—a routine matter in a country bursting with inhabitants, looking to give jobs to as many people as possible. When you arrive at the airport or at hotels, you often find three times as many workers as is needed for every job. That is also the reason why Indians sometimes reject technology and tighten import controls. In Delhi, for instance, there are hardly any supermarkets, so as not to harm the small vendors.

“I had an idea for a Fricassee night for the embassy employees,” Koresh recalls, “it took me two weeks to collect the ingredients for a meal that would last half an hour. They don’t have everything here. Cheese, for instance, is very expensive. To make a cheesecake you need a cheese alternative.”

Those who keep kosher might find themselves looking for a milkman on the street, like Eyal Falah, a consulate worker in Mumbai. “There are all kinds of gods and beliefs here,” Koresh adds, “there are those who don’t eat roots and those who don’t eat eggs. And as a diplomat, you have to be prepared to cater to them all.”

But the greatest difficulty is the distance from Israel. Finkelstein has been serving in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for 16 years. He is 44 and has four children. Prior to his mission in India, he was dispatched in South Africa, Poland, and Azerbaijan. “A modern Bedouin,” he calls himself, “on the one hand, not many professions allow this kind of life. To be involved in historic processes, to meet with heads of state. In Africa, I met the Zulu King. On the other hand, you have to uproot your family. It affects the first child most, the second child less so. Prior to India, we stopped in Israel for four years. We wanted the children to get acquainted with the Israeli experience.”

Kadosh adds, “The kids are born into it, they don’t know anything else. They love the experience of a diplomat's child. Hosting on Fridays, conversing with writers and politicians, enjoying a meeting with a famous athlete, or greeting (Prime Minister) Netanyahu on the red carpet. And there are also the difficult moments, like when there’s a family event in Israel and everybody posts lovely photos on WhatsApp. Those are ‘bummer’ evenings.”

Koresh, a single-mother serving in Bangalore with her six-year-old son, Ofek, knows the feeling. “Every time I leave the country and hug my mother, I tell myself with some anxiety that this cannot be the last time.”

On the way home, when the Dreamliner’s wheels leave the runway at Gandhi Airport and the plane accelerates, India looks much less crowded from above, much more tolerable and pleasant. And when the subcontinent becomes just a spot, it’s hard not to think about all the hundreds of millions left to struggle down below, about the children who are swimming in monsoon-swamped streets in Mumbai, or the barbershop that operates on the sidewalk in Delhi with two mirrors stuck on a wall—moments of magic in an enigmatic country.