The loss of an IDF legend

Standing head and shoulders above his comrades, Yossi Dirhali had the reputation of fearlessness and heroic bravery that earned him two military medals; it is almost ironic that he was brought down by a small piece of shrapnel

In the summer of 1971, a Druze shepherd got caught in an unfenced minefield on the Golan Heights, and stood on a mine. The mine exploded and the shepherd was seriously injured.

The IDF soldiers and officers who rushed to the scene were at a loss as to how to rescue a man from the heart of a minefield. Then a jeep arrived and a young officer, two meters tall, jumped out.

"Yossi Dirhali is here," said the gathered crowd with a sigh of relief.

Dirhali, the commander of Company B in the elite Egoz Unit of the IDF, did not hesitate, nor did he show any fear. He took an army knife, grabbed a stretcher and got down on all fours, crawling through the minefield, stabbing the knife into the ground every few inches, until he had cleared a path to the shepherd.

When he reached the wounded man, he placed him on the stretcher, and with the help of another officer who followed in his wake, pulled the shepherd out of the minefield.

For this act of bravery, Dirhali was awarded the Medal of Honor. It was his second military decoration, after he received the Medal of Valor for a rescue under fire.

The story of the minefield rescue is just one of many about the adventures of the late Captain Yosef Dirhali, and sheds some light on why this young man, who was killed 47 years ago, left an indelible mark on everyone who knew him.

Yossi Dirhali did not come from a privileged, suburban family. He was the son of Georgian immigrants, who lived in Jaffa. But despite his humble beginnings, at the time of his death he was already a living legend.

He was the commander of a venerable company from the Egoz reconnaissance unit who was worshipped by every soldier in the Northern Command, from the lowliest private to the commanding officer.

Everyone was convinced that one day he would become the army's chief of staff, but Dirhali was killed before he could fulfill his promised future. He died in yet another daring rescue, this time of soldiers wounded in a Syrian raid on the Golan Heights.

A mother's love

Dirhali was born in 1950 to a traditional Georgian family who lived in a high-rise block in southern Jaffa. He was a huge boy with enormous physical strength and a somewhat wild personality. He bounced from one high school to another before enlisting in 1968, and ended up in Egoz, a forerunner of the contemporary unit that took its name.

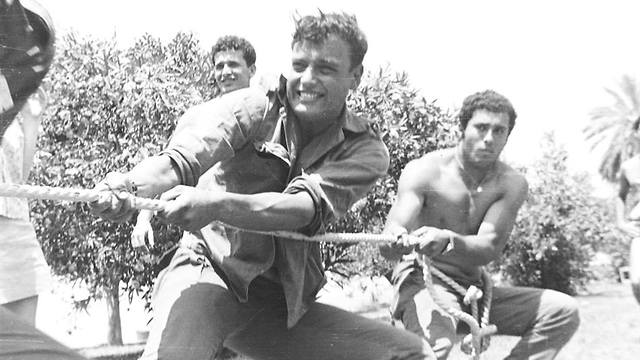

His deployment to Egoz was a seminal moment in his life: Dirhali flourished there as if he had been born to it. His enormous physical fitness, skills of bravery and navigation, adeptness in operating weapons systems, rich charisma and leadership, insightful intelligence reports and perhaps above all his tremendous courage made him the ultimate soldier and officer.

Dirhali's abilities were so exceptional that rumors quickly began to circulate among the high command of "the best soldier in the IDF." Before long, Dirhali would take over Company B, which, in the eyes of every one of its soldiers, was the unit's finest.

"Dirhali was a punk who roamed the streets of Jaffa. But he had a mother made of granite. She forced him to attend high school, she forced him to matriculate; if not for her, he would have ended up on the streets," said one of his friends at a memorial last November at Dirhali's grave in the Kiryat Shaul military cemetery in Tel Aviv.

"I'm standing here at Dirhali's grave," says Avi Yochanan, the commander of Company B, "and I don't understand how such a small grave can hold Dirhali the giant." The guys laugh, staring at the grave in almost complete silence. "All the memories of Dirhali are classified because they are on the verge of being criminal."

They all laugh again, with more than a hint of sadness.

"I first met Dirhali in August 1970, when I was appointed Egoz commander," says Major General (res.) Uri Simhoni. "He was then the deputy commander of Company B. It was at the end of the War of Attrition in the north, and the border with Lebanon was still largely open, with no fence and no warning systems, and the north suffered constant incursions."

"Dirhali immediately stood out in every operation," Simhoni says, referring to the cross-border raids to eliminate terrorist strongholds and the ambushes with night vision equipment. "He was exceptionally talented, very clever and probably the most physically powerful officer in the entire IDF. I always put him at the back in every operation so that he could carry whoever fell behind."

And Simhoni, an experienced, veteran officer with many feats of his own, drops his usual calm façade when he talks about Dirhali: "I loved him like a son, there is no more to say. He died at such a young age, just 22, but his legacy remains in Egoz until this very day."

The fall of friend

"Dirhali was a platoon commander when I joined Company B," says Brigadier General (res.) David Agmon, who later became an officer in the infantry and paratroopers.

The objective of the operation in the Lebanese village of al-Khiam was to liquidate a terror base. During an assault on a building in the village, Egoz officer Lieutenant Dubi Adar was mortally wounded. "Dubi came from a northern family with an attorney for a father, while Dirhali came from the streets of Jaffa," says Agmon. "But the two were friends, heart and soul."

When Dirhali heard over the radio that Dubi had been wounded, he abandoned his own position, ran to the scene of the incident through enemy fire on all sides, loaded Dubi on his back and ran up the hill toward the extraction point. It was for this act that Dirhali received the Medal of Valor, but Dubi died of his wounds and Dirhali was inconsolable.

"After Dubi's funeral, Dirhali visited me in hospital," says Agmon. "Suddenly, the big, tough Dirhali began to cry. 'Dubi's gone,' he told me, and I - bedridden with a hand and a leg in the air – had to comfort him.

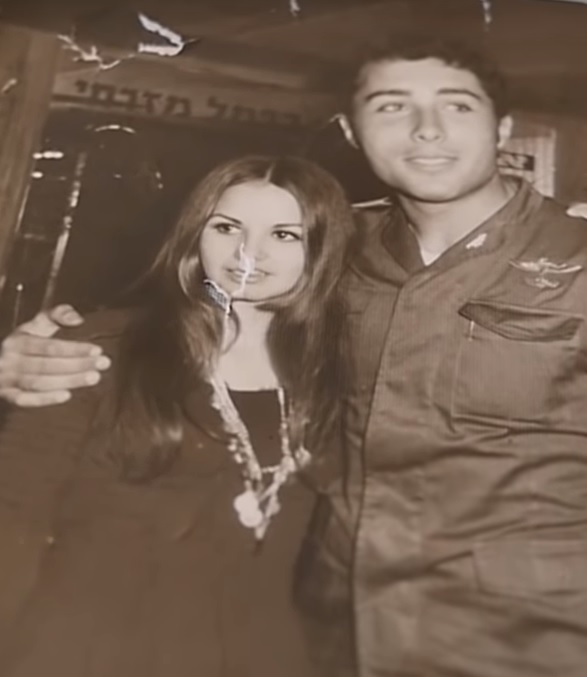

"After Dubi was killed, suddenly he was another Yossi, who shut himself up at home on weekends, brooding. He loved Dubi and it was very hard for him," recalls Rachel Radko, who was Yossi's girlfriend at the time.

"We met when I was 16. He saw me dancing at a party and said, 'I am going to marry her,' and that was before we'd even exchanged a single word."

Rachel's stories present an entirely different perspective of Dirhali.

"He did so many emotional and gentle things that do not correspond with this macho man who wandered around the army making everyone tremble," she says. "And that's how I want to remember him. A family man and a humane man who could not bear to see anyone suffer and who performed many small gestures.

"For example, he could not bear for me to hitchhike home from my army base. I would go home every two weeks and Yossi would almost always come to collect me. 'You're not (hitchhiking),' he would say, 'I am coming to collect you.'"

Rachel says she has experienced post-traumatic stress since Dirhali's death. "When my own son enlisted, I took it very hard. He would get on the bus and I would think, it was over. It was as though I was reliving Yossi's death all over again."

The two seemingly contradictory sides of Dirhali's personality are raised by almost everyone. This is true of historian Prof. David Ohana, who was a soldier in Egoz during the 1970s. "I was a lowly soldier who arrived at the glorious Company B," Ohana says.

"Dirhali's fearsome reputation preceded him. An impressive figure like no other, he was exceptionally tough and frightening, but also paternal and compassionate at the same time," he says.

"He had no problem jailing a unit driver for a minor offense, but on the other hand he would return at dawn from a night operation and stand for hours in the kitchen peeling potatoes so that we could all have chips. He would also read literary and philosophical masterpieces, and would spend hours debating intellectual topics with me, the lowly soldier."

Death of a giant

Dirhali's death in November 1972, was a sad echo of his entire military service: rescuing the wounded under fire.

"I will never forget that day," says Ohana. "There was a Syrian bombardment of Quneitra, and he heard that some of the wounded had taken shelter – ironically - in the Muslim cemetery there." Dirhali did not think twice, took a half-track driver and drove straight into the site of the shelling without any fear.

The artillery barrage did not stop, and a fragment hit the back of Dirhali's neck. "The helmet he wore did not help," says Ohana. "He had a huge head and his steel helmet sat on him like a yarmulke. And so the shrapnel went straight into his neck."

"I do not remember how I got to the hospital," says Rachel. "I just remember sitting next to him, it was like he had gone to sleep and should wake up at any moment. It took five days. And I will never forget the sound of helicopters constantly circling over the hospital."

"He lay unconscious in Rambam (in Haifa)," says Simhoni. "I stood at his bedside and consulted with the hospital chief. I asked him to bring him the greatest expert in the country for such injuries. I sent a helicopter to Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem to bring in Prof. Aaron Beller, who was a senior neurosurgeon at the time.

"Beller examined him, looked at the X-rays and said - I remember it word for word - 'Why did you bring me here? He is a dead man, you should not have sent a helicopter.'"

"I asked the medical team how long he would keep breathing," Simhoni says. "They replied – 'until the next power cut.'"

Dirhali died the next day.

"A small piece of shrapnel brought down this giant who stood two meters tall," says Rachel. "I always felt so protected by him, and then he was just lying here, eyes closed, hooked up to to pipes, and lifeless."