Giving Judaism new meaning

More secular Israelis counter void within them by taking up Torah, Jewish studies

The average secular Jew in Israel is a sad paradox: He is Jewish, but does not know how to read Judaism. He is educated, a worldly person who can quote Nietzsche and Plato, but has given up on himself and his roots long ago.

It took many long years until Katznelson's words trickled down to the right places, but in Israel 2010 there are quite a few seculars who are aware of the problem and are trying to change the situation.

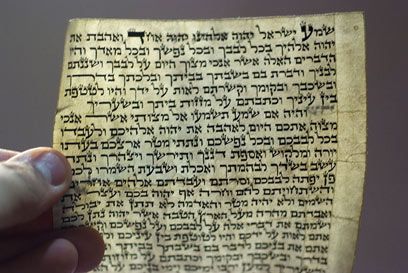

Renewed interest in Torah (Photo: Israel Bardugo)

At the heart of Tel Aviv's southern-most neighborhood, opposite the central bus station, among the dubious businesses and the labor migrants, lays the most secular yeshiva there is. A stack of books for sale can be found at the entrance to the modest building: The six orders of the Mishnah, at subsidized prices. Opposite the books, a young man and woman can be seen leaning over a desk with notebooks. In Tel Aviv's July heat, the two are wearing short sleeves – not afraid of being exposed before the Jewish materials on their desk. They are part of the Bina Yeshiva's pre-military service preparatory program.

Omer Sheli, 19, signed up for the Bina course for the Jewish education. His parents were indifferent to tradition – sometimes they had Shabbat dinner, and sometime they didn't. He also never showed interest in Jewish studies until he reached high school and registered for a new course – Jewish heritage. There, with his Jewish heritage teacher, he came to understand just how little he knows.

Today, 10 months later, he feels different. "I am no longer an 'empty vessel,' I have undergone a process. I feel that I have formed a Jewish identity, I have created for myself mental strength that I did not think was possible."

Gal Amoyal, 19, is Omer's classmate at the yeshiva. Gal was brought up in a completely secular home, where holidays were celebrated only as a family event. She was originally interested in philosophy. Bible studies at her school were minimal and the option of signing up for a course on Jewish heritage did not exist. She said she also went through a deep process.

"When I arrived here, my interest was based on my anger towards what I knew about Judaism. Today I feel like have not fully exhausted anything yet. I am not satisfied; I still have something to strive to," she said.

'Shake dust off of Judaism'

Omer and Gal are upset that the society from which they emerged is shut off from the Jewish world. They disagree with the conservatism. Not the religious conservatism, but the seculars' conservative approach.

"I don't mind the lack of knowledge, but I do not understand the intolerance towards Judaism," said Omer. "In the past year, I have discovered that secular society is conservative. The religious have their own values, norms and red lines that we like to criticize, but the seculars are the same. They are not willing to give up on what they know."

The secular yeshiva students occasionally attend classes with students from religious yeshivas, who support bridging gaps. Gal and Omer speak of the praise they have won for their ability to learn. They still have far to go in order to close gaps vis-à-vis the other students, but now they already know what they have yet to learn.

The yeshiva's head, Eran Baruch, is a proud redheaded secular who found himself somewhere on the spectrum between the kibbutz he grew up in and Jewish studies. He does not have a beard or wear a skullcap, but he is Jewish with every fiber of his being. He knows how to engage in debate, and can interpret the texts in many ways. He is no different from any well-known rabbi in Mea Shearim.

"Secularism today is at an all-time low," Eran said. "There is a great void and the only answer is to shake the dust off of Judaism, to unearth Katznelson, Rachel the Poetess and Brenner, and build secular yeshivas, and lots of them, all over Israel."

According to Eran, secular Judaism is social Judaism, a form of Tikkun Olam, which is why he placed his students in the darkest part of Tel Aviv. This is why they volunteer to help anyone under the biblical definition of "foreigner" or temporary resident of this land.

"We are not trying to invent anything new, just restore," he explained. "We are facing an existential crisis because someone decided to have a monopoly over Judaism."

'Alternative for seculars'

In Jerusalem, two friends in their 30s, "who are in love with the city despite its negative image," are working on a secular yeshiva of their own.

"We are in the midst of a very serious leadership crisis in Israeli society," said Avishay Wohl, a teacher and graduate of the Institute for Teacher Training for Humanistic-Jewish Education. "There are large economic gaps as well as social alienation in the country. And if that's not enough, we also see a trend of religious radicalization on the one hand, and contempt for Jewish tradition on the other hand. We decided to offer an alternative for seculars who are interested in Judaism, in Jerusalem of all places."

Three years ago Avishay began organizing study and poetry sessions at his home. These gatherings turned into a success story. Avishay, along with his friend from university, Ariel Levnison, 31, decided to take it one step further – to open a yeshiva. Unlike the secular seminaries meant to acquaint the uneducated and the ignorant with scripture, they hope for a revival – creating Jewish dialogue, writing about Jewish subjects and not bowing down to ultra-orthodox Judaism. In order to reach such a point, one must study, and a lot.

Avishai and Ariel's curriculum looks like a basic training crash course for yeshiva boys. Studies continue from eight in the morning until eight at night. After that, members of the yeshiva take part in community work.

Mati Hai, 55, is a Jewish activist and one of those few people familiar to anyone engaged in secular Judaism. Mati grew up in a home with a devout father and mother who turned secular as result of the Holocaust. Perhaps this is why it's easier for him to shift between the religious and secular worlds.

Mati scampers around pre-military schools, Jewish research and philosophy institutes, and meetings between religious and secular Israelis while trying to explain that Judaism is not merely a religion.

"Judaism is also about culture and a world of morality, values, tradition – and also, among other things, religion," he says.

In his view, the difference between a religious and a secular person has to do with the number of answers.

"A classic religious person believes wholeheartedly that he possesses the truth; he looks at the secular and knows that he's wrong. Meanwhile, a classic secular believes that the number of answers in the world is like the number of people. To my regret, many people out there turned secularism into a religion and now they have only one answer."

'Finding Judaism in kibbutz'

Kibbutz Beit HaEmek, one of these places where Judaism was shunned, leaving secularism as the only option, is home to Benjamin Yogev, 72. For years, he managed the "Holy Day Institute" at Kibbutz Beit HaShita along with Aryeh Ben-Gurion (the prime minister's nephew.)

Ben-Gurion sought a way to express his Judaism in the kibbutz framework: What to do on Friday evening, how to address boys who turned 13, and how to mark Yom Kippur. The kibbutz atheists created their own lifecycle while marking the holidays in their own way. Most Jewish holidays were easy to celebrate without getting involved with Halacha and while staying away from the "Old Jew" image they left behind in the Diaspora.

"Today, you will find Jewish texts in the library of any kibbutz," Yogev says. "On the other hand, privatization prompted some kibbutzim to shun community ceremonies on religious occasions. The holidays have changed."

Meanwhile, some of the kibbutzim in the Jezreel Valley established synagogues in recent years. Some Kibbutz members also attend the Oranim College in order to study Torah. On the last Shavuot holiday, they held nighttime Tikkuim and studied the Scroll of Ruth and other Jewish texts.

The haredim refer to the seculars as "captured babies" – Jews with no Judaism within them who are like empty vessels from the moment they entered the world, and therefore should not be blamed. However, contemporary free Jews, those who voluntarily chose it, have not been captured or empty of substance for a while now. They're simply too few to make themselves heard in a state replete with religious camps and branches like Israel.

- Follow Ynetnews on Facebook