'I didn't raise my children to hate Arabs'

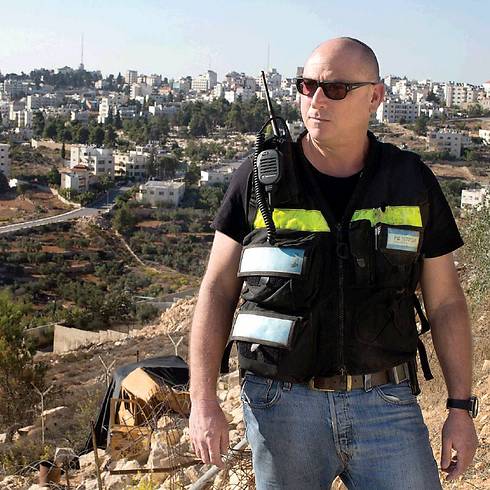

After 27 years, two intifadas and even a life-threatening gunshot wound, security officer Avigdor Shatz, aka the sheriff, is leaving his job as security officer in the West Bank, and he has plenty to say about Palestinian folly, price tag attacks and young Israelis' fondness for hitchhiking.

With all due respect to titles an individual may amass during his or her lifetime, the highest social ranking probably belongs to those known far-and-wide by their first names only – Madonna, Adele, Beyoncé and others, who need no further introduction. In the Ramallah sector, this honor is reserved for Avigdor Shatz.

All those who travel the roads of the Mateh Binyamin Regional Council are familiar with the Avigdor brand, behind which stands the longest-serving security officer in the territories, the man who has seen everything and has been hit by everything, the man who some fondly call "the sheriff."

Shatz has been patrolling the roads around Ramallah since the late 1980s. During this time, he's managed to sustain critical injuries in a terror attack, star in death notices, and also, in contrast, meet in private with the former head of the Palestinian Preventive Security Force, Jibril Rajoub. Shatz has handled hundreds of accidents, terror attacks and infiltration incidents in this time too.

Last summer, for example, his command center was the first security entity that received a call from Ophir Shaer, the father of the late Gilad, after the abduction of the three Jewish teenagers. Now, at 52, he's decided to hang up his guns and communications radios, and, for the first since 1987, go to sleep without a beeper next to his bed. "I've done my bit," he explains in his thick voice. "It's time to pass on the baton."

Meanwhile, he remains in his war room on the ground floor of his home in the settlement of Shilo, surrounded by three plasma screens, and with a variety of devices hang from his belt.

A Kalashnikov in the head

It all began when Shatz found himself in the territories at the age of 17, a yeshiva student from Pardes Hanna who wanted to see this Samaria that everyone was talking about. By chance, he ended up in Shilo, where he married a local girl and remained. In 1987, he was appointed security coordinator of the tiny settlement, and thrown headfirst into the first intifada.

"I used to patrol the neighboring village of Sinjil, at noon, when the Egged bus would pass through. I'd stand outside the village school so that the pupils wouldn't throw stones," he recounts.

Back then, Shatz didn't get a car, only a gun and a walkie-talkie. There was no fence around the small settlement, and certainly no security cameras in place.

Subsequently, in the early 1990s, he was appointed chief security officer of the Mateh Binyamin Regional Council, and his work conditions were upgraded thanks to a used Subaru he received for the job. The council's security department numbered just two people at the time. The department he's now leaving comprises 10 graduates of elite Israel Defense Forces commando units who know the area like the backs of their hands and conduct training courses for security coordinators from all over Israel.

Shatz came close to parting ways with the world for the first time in 1998. At the Wye Plantation in Maryland, the politicians were speaking about bringing peace to the region; and on the outskirts of Ramallah, Schatz accidentally ran into an outpost of the Palestinian Authority's Force 17, a special-ops security unit.

"We were dealing at the time with a group of terrorists who used to throw stones from a moving vehicle," Shatz recalls. "That night, we received a call about such an attack between Beit El and Ofra. I quickly made my way to the scene and, at the same time, alerted the ranger, Yaakov Dolev, who showed up from Talmon."

On reaching the entrance to Ramallah, Shatz was passed by a Mercedes van; and seconds later, a large rock smashed the windshield of his car. He was convinced this was the terror cell he had been after for some time. "I started chasing them with my head out the window; at the same time, Yaakov came in from the north and we began a chase using sirens into Ramallah."

Some 200-300 meters into the city, the two were stopped at a Palestinian police checkpoint. The Mercedes disappeared. Dolev rolled down his window and addressed one of the policemen in Hebrew: "That car is throwing stones at us. Take the information and deal with it." The officer, in response, cocked his weapon and started shooting around the two cars.

Shatz and Dolev were unaware that they had stopped outside Mahmoud Abbas' heavily guarded residence. Abbas was at the Wye Plantation at the time.

"His security guards came flying out at us in ecstasy," Shatz recalls. "Dozens of armed men began whistling, shouting and shooting around us. Our accessorized vehicles led them to believe we were commandos. In the end, one of them came over and smacked me in the head with the butt of a Kalashnikov."

Did you consider the possibility that you may die?

"It was quite possible. I was a walking wounded. I was bleeding from my ear and I was bruised all over."

At some point, a white jeep belonging to the Palestinian security forces pulled up and the two men were bundled inside and taken to the Muqata compound. The area was filled with people when they arrived. Armed men were firing into the air from the rooftops. Whistles and shouts filled the air. Following a nerve-wracking wait in the jeep, Shatz and Dolev were told that only one of them could enter. Shatz stepped forward.

"A path opened up for me among the crowd and I walked through to Jibril Rajoub's bureau. We shook hands inside and he said to me in Hebrew: 'Don't worry, I'm sending you back, everything's okay.'"

The two were then driven to the Liaison Command Center where they were handed over to the army with nothing but their torn clothes on their person.

Like a kick from a horse

The security situation in the area worsened two years later with the outbreak of the second intifada. "It was a crazy time – a time in which you'd leave your house every day and have no idea when you'd return," Shatz recounts. "My children didn't see me for long periods. I had clothes in the car and everything I needed."

Schatz and his men arrived on the scene of dozens of shootings attacks and cared with their own hands for hundreds casualties, but nothing prepared him for the morning after which his friends were informed, in disbelief and sorrow, of his death.

Taar Hamad, a shepherd from the village of Silwad, found a Jordanian sniper's rifle and decided to kill Jews. On March 3, 2002, he took up a position on a mountain across from an IDF outpost in Wadi Harmiyeh, set up his rifle some 70 meters from the checkpoint, took aim at the head of a soldier and squeezed the trigger. He managed to kill 10 people before fleeing back to his village.

"A friend called me at six-thirty in the morning and told me he had heard that the checkpoint was under attack," Shatz recalls. "I thought to myself that someone had fired off some rounds or had thrown a grenade and fled, as had happened often around that time. I got to the wadi, put on an identification vest, called for a bulletproof ambulance from Ofra, and got out of the car to treat whoever required care.

"Outside, I could hear the sound of single shots from the west. I was sure the shots were coming from our forces. Terrorists, after all, fire off a series of rounds and make a run for it… And just then I realized that something bad was happening. At every incident, there's always someone who's shouting, someone who's making a noise and someone who's administering treatment; but in Wadi Harmiyeh, there was absolute silence."

Shatz recounts the incident like a man giving testimony to the police, without a trace of emotion. "I saw a parked Nissan car, and its driver was slumped over the steering wheel with a bullet in the head. The soldier at the FN MAG (machine gun) also had a bullet in the head. And I saw another soldier lying next to him, also with a bullet in the head. I'm standing there looking around when the deputy commander of Battalion 77 arrives. I see him get out of his vehicle, his medic gets out the back, and is immediately struck by a bullet in the arm. I realized then that the shots weren't coming from our forces. I bent down to pick up the Glilon rifle of a soldier who was lying alongside one of the concrete barriers with a bullet to the middle of his face. Just as I'm standing up, I feel a blow. I realized I'd been hit too."

How does it feel?

"Like a kick in the back from a horse," Shatz says. "You realize right away that you've taken a bad hit. At this point, you have the choice to die there and then, to take your last breath and disappear, which is the easiest; or you choose to function. I relayed a message on the radio and realized I needed to start getting myself out of there - because if I don't get out of here right away, I'll die.

"I looked at my chest and wondered how much longer I had to live. I managed to move away from the checkpoint, and then I saw the armored ambulance I had called in from Ofra. I could see that it was moving forward slowly, and that there were soldiers behind it who were trying to return fire at the source of the shooting. I reached the ambulance and fell onto the paramedic. They laid me down on the bed; and I said to them: Guys, come on, get going."

The ambulance team was horrified to see the local sheriff in such a state, with his entire upper body drenched in blood. "There aren't many instances of survival from such injuries," Shatz says today with an air of calm. That morning, in the ambulance, he begged for something to numb the pain. "As a trained ambulance driver, I was a terrible patient. I drove the entire team crazy and barked instructions all the way. At one intersection, they stopped to find available veins, and I scolded the driver: Come on, drive. What are you stopping for?"

Meanwhile, the GOC Central Command informed the council head, Pinchas Wallerstein, that Avigdor Shatz had been killed, and the ZAKA organization issued a death notice for the acclaimed security officer. The sad news soon spread throughout the area, and the unofficial death toll from the attack rose by one.

"I reached (Hadassah Medical Center) Ein Karem completely swollen up. They admitted me to the Trauma Ward and put me under. The inserted five drainage pipes into me and I didn't respond. They then transferred me to surgery, sawed my ribs apart, and followed the path of the bullet until they came to a torn windpipe. This is an injury the doctors were not familiar with in living patients, because one usually dies from it on the battlefield.

"I was fortunate to have been taken to an excellent Israeli hospital. Because what are Israelis good at? Improvising. They decided to try to repair the trachea and wrapped it with muscles from elsewhere to see if it could close. My family was informed that the doctors were not sure if I'd live through to the morning, and that if I did, it would be a very lengthy rehabilitation process and that I'd remain in an induced coma for at least a month."

Shatz woke in the morning from the anesthetic into "a tremendous effort on the part of your muscles to continue breathing. You say to yourself: What do I need this for?"

Prolonged physiotherapy and a long and painful rehabilitation process saw Shatz return to his fierce-looking jeep and the position from which he was unable to part.

Did the experience cause a change in your attitude towards the Palestinians?

"I was very seriously wounded, and it's a significant family trauma. Ostensibly, I had all the reasons in the world to generate hatred. But I didn't raise my children to hate Arabs. I myself received a certificate of appreciation from the governor of Ramallah for the help I gave to Palestinians at various incidents as a member of the Binyamin Council rescue unit."

The man who steps into Shatz's shoes will inherit a population that is aware of the dangers around them on the one hand, yet doesn't really adhere to the security regulations on the other. The settlers are still hitchhiking, for example, despite the kidnapping and murder of three teenage boys last summer.

"It drives me crazy," Shatz says. "People don't realize that there are terror cells on the loose that are looking for someone to abduct. It freaks me that people allow their children to get around in this way. It freaks me out that kids are out on the streets all over the place with no money for the bus. It freaks me out girls from Ma'aleh Levona stand at Rahelim Junction at night and wait for a ride home. After all, they have as much chance of being kidnapped as they do of hitching a ride.

"It freaks me out when people say that it's ideology. I can only ask, beg and cry. We visit boarding schools and schools and give lectures about it, make every effort to prevent it; but the bottom line is if there is another kidnapping here, it will pain me but it won't be surprised."

What do you think of the 'price tag' incidents?

"In my view, Jews who attack Arabs will also attack Jews. This is a criminal culture that harms us, the settlement enterprise, first and foremost. The people involved are usually poor kids who have lost their way, and the adults behind them turn it into an ideology and political capital. Unfortunately, these poor kids are no less a threat to the settlement enterprise than the Arabs, and they may be the best thing that has happened to the left in Israel."

Where is this region heading? How do you see the future of the settlement enterprise?

"Things are different today, different from what they used to be. The Palestinian Authority today is far more well-trained and proficient. There's an American general who is training Palestinian forces, which are accumulating know-how and skills. You can't compare the Palestinian policemen who fired at us during the second intifada with what we are up against today in the PA.

"As for the chance of us living here together – I'm more of a skeptic today, because I see the fourth and fifth generations throwing stones. I see 10-year-old children whose grandfathers threw stones at me, and they are doing the same, so I'm not optimistic."

Is there a solution to this intifada?

"Of course there is. At present, concerted efforts are being made to deal with the incidents and, in the same breath, convey a sense of business as usual. Palestinian workers continue to enter Jewish settlements every day. I don't buy the notion that they have nothing to lose, that they are being led by desperation. That's nonsense. The Palestinians have a lot to lose. Their quality life is high: I see a lot of new cars on their roads; the Ramallah skyline is high and modern; and business is booming."

So you don't see an intifada on the horizon in Judea and Samaria?

"At this point in time, I don't sense it in the air."

Do you see the possibility of a peaceful life together?

"A peaceful existence is not part of the agenda of ether side today. The Palestinian problem hasn't evaporated. If only the Arabs would accept (Egyptian President) Sisi's solution that proposes a Palestinian state in the Sinai. In the meantime, each side is trying to wear down the other, and hoping in the end for a proposal that would transfer everyone out of here."

Can two million people be overcome?

"Thus far, we've been doing it – because, among other reasons, they haven't given us a reason to change the situation, the idiots. They screw themselves with their hard-headed positions on issues such as Jerusalem, the right of return, the Jordan Valley and the 1967 borders. In a nutshell, what the settlement enterprise is doing is bringing the situation to the point of no return."

Will you continue living here under Palestinian rule?

"That's a hypothetical question; but I won't remain here as a non-Israeli citizen. If a Palestinian state is forced upon us, I won't remain here. I have no intention of living in a country that isn't mine."

And if Jews were to remain here, would you agree to be their security officer?

"No, they can ask Jibril Rajoub to protect them."