Farewell to Sisyphus: Peres won in the end

Op-ed: In spite of Shimon Peres’ many accomplishments and contributions to Israeli society, in general elections, he tended to lose. But in his final days, Peres won, and secured his place in history.

“You’re done burying Mitterrand, so now you’re here?” is how Shimon Peres greeted me when I walked into his office in late February 1996, two days after the No. 18 bus suicide bombing, when Peres was prime minister. He sounded lost. A deathly silence pervaded his office—a feeling that this was the end of the road. Did he already sense that he was going to lose to Benjamin Netanyahu in an election that was supposed to be a walk in the park for him, in light of Rabin’s assassination? Shimon Peres, the man who didn’t know how to win the important political battles in his career, was en route to being defeated once more.

Perhaps he felt back then like the mythical Sisyphus, sentenced to push a boulder up the mountain, only to see it rolling back down at him endlessly. The gods punished Sisyphus for disrespecting them and revealing their secrets. No fate could be worse, the gods reasoned, than feeling like you’ve almost reached the summit—only to then have to start from scratch.

Like a giant surrounded by small-minded people

The French philosopher Albert Camus offered a different view of Sisyphus: perhaps he derived his joy from the journey, from the act of pushing itself. It’s doubtful whether Peres took any pleasure in his record of being defeated by Rabin, Shamir and even Moshe Katzav when he first ran to be president. Nonetheless, Peres never lacked the stamina needed to keep pushing, in hopes of getting to breathe the fresh mountaintop air. When everyone around him was frustrated, Peres kept going, arriving early in the morning to his office—even after roomfuls of activists shouted at him that he’s a loser the night before.

Peres refused to disappear or make way for others, not just because of his ego and will to prove everyone wrong, but also because he always felt like a giant compared to his peers—like a man of vision amid small-time meddlers—and he couldn’t get why his colleagues don’t see the greatness that he has to offer. He was chasing recognition and prestige, and he had an insatiable hunger for being praised.

Most of the time, Peres walked around feeling that those in his milieu can’t grasp the sophisticated language he speaks, sometimes arrogantly and always highfalutin—a magician with words.

Peres was responsible for many positive developments in Israeli politics, but he also introduced much darkness into it. This combination was Peres’ signature in the political arena, a multidimensional man of contradictions. Wherever he went, he was seeking attention and affection. “So, how’d I do?” was the first thing coming out of his mouth after giving a speech, or offering what he thought was a brilliant insight, addressed to anyone who happened to be near.

He wanted to be told how great and wonderful he is

It’s as if within him was a bottomless well. In his eyes was yearning for recognition, for affection. He wanted to be told how great and wonderful he is, to be celebrated for his wit and prescience. But the well had always remained empty because Peres felt that he never got all that he deserved.

He compensated for the emptiness by trying to please everyone, all the time. That’s why, it seems, he couldn’t go all the way politically and make bold moves in light of opposition. He was just too occupied, whether consciously or not, with placating everybody. His need for adulation was rooted in always feeling like the foreigner, a Jew of the Diaspora.

“There’s no way around it, for people of my generation, the number question is: where were you in ’48?” Ezer Weizmann, who was at times a close friend of Peres, once told me. “It’s a loaded question, it’s not like asking where were you in the Sinai campaign, or the Yom Kippur War. And there’s no way around the fact that Shimon was never in the army. He did a ton for national security, working in munitions and procurement, but he didn’t talk like the army guys did, he just couldn’t pull that off.”

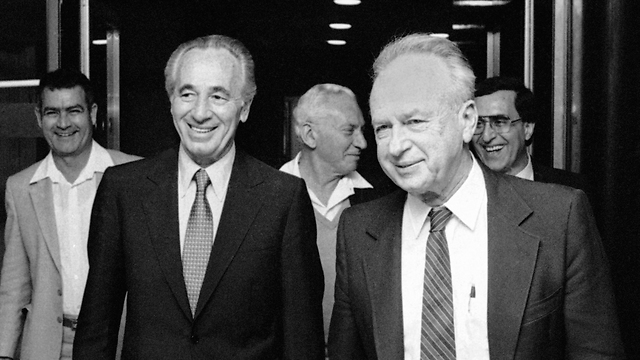

Peres was the total anti-Sabra compared to his political rival and later close friend, with whom he’d have a love-hate relationship for decades—Yitzhak Rabin, who was perceived as the perfect Sabra. When Rabin would mess up in public sing-alongs, it was seen as endearing; when Peres did it, it only contributed to his image as a foreigner who didn’t grow up with the same folklore (in spite of having arrived to Israel at a young age).

A foreigner who wasn’t part of the gang

“Handsome” was never an adjective used for Peres. Whenever people described Rabin as handsome, Peres would be fuming inside. He felt the same way when he watched as another foreigner, Dan Ben-Amotz, who had studied alongside him at Ben Shemen village, came to exemplify the “ideal” Sabra.For years, Peres felt that he was tilting at windmills. Politically, every initiative of his had failed. He felt that he had been cursed, and misunderstood, that he’ll forever be more appreciated abroad than he is in his own country. During campaigns, his political foes would spread rumors about him, like that he had stocks in the company Tadiran and that his mother was an Arab—all because he was never part of the gang, never one to run on rough terrains in battle with the macho army guys.

“I had never asked for a thing for myself,” Peres told me almost every time we met. “What I’m interested in is achieving peace. Building a new Middle East. No one will stop me.”

It’s true he was totally committed to bringing about peace. He wanted to find a solution, badly. But he had also asked for quite a lot for himself. Sometimes, he worked subversively to get his way, and other times he would operate by way of pleasant diplomacy. Peres didn’t always toe the party line and his methods defied simple characterization. He was intellectually curious and he knew how to inspire. He was second to none in his creativity in politicking, for better or for worse.

It’s only in the final stage of his career that Peres managed to achieve what he had always wanted—to win, and to be adored. To be celebrated not just abroad, but also in the place he loved most, his country.

Mitterrand’s star eulogist

There are few who have achieved operational successes as Peres has: weapons trade deals, building up the Ministry of Defense and the nuclear reactor in Dimona, the Oslo Accords with the Palestinians. But in the real test that every politician faces—winning elections—Peres was doomed to fail and I saw this fear of failure in his melancholic gaze that same day in his office in February of 1996. He was appointed prime minister, but decided to go to elections early so that no one could say he had “inherited” his position. He wanted to be chosen by the people. He didn’t want to have the throne by default, or because Rabin’s blood was shed in a Tel Aviv square (the man who termed Peres a “master manipulator,” a label that would stick).That decision, to have elections early, was Peres’ cardinal error. He was the one who inadvertently turned over the keys to the kingdom to his arch-nemesis, a man Peres didn’t trust or believe in, Benjamin Netanyahu. “The one who just finished high school,” as Peres once dismissively referred to Netanyahu.

I saw Peres a few weeks prior to the election in Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, when he came to pay final respects to his good friend and President of France, Francois Mitterrand. It was after Rabin’s assassination and before Peres had decided to go to elections early.

If it weren’t for funeral etiquette, Peres would have received a cheering, standing ovation that day. Bill Clinton and Helmut Kohl were there, as well as John Major and Jacques Chirac. As Peres made his way to the stage, these world leaders all rose. I remembered how in the past crowds hurled rotten tomatoes and eggs at Peres in party meetings, how they called him a traitor and accused him of wanting to divide up Jerusalem. But that day in Paris, he was the star. French TV picked him to eulogize Mitterrand, a leader whom Peres admired. When asked in Paris “What will be next?” Peres, optimistic as always, said that peace will prevail and that it can’t be any other way what had happened in that Tel Aviv Square.

It seemed, back then, that a moment of trauma was transformed into euphoria. Peres really did believe he was going to defeat Netanyahu in the general elections and become Israel’s prime minister in earnest. Even Peres’ political rivals predicted that he would finally shed his “loser” label, and that he couldn’t lose this time even if he tried.

Yet, like Sisyphus, Peres pushed his boulder up the mountain all his life, only to watch it roll back down—and once again, to start from scratch.

Throughout most of his political career Peres was an indispensable right-hand man, first for David Ben-Gurion and later for Rabin. And still, there was no one who hated being in that position more than Peres, so he was scheming obsessively to try to get to the top. This scheming is ultimately what got him further away from his goal; he wanted too much and too fast, and made many mistakes along the way. “I’m not Sisyphus,” he told me once. “I always get the boulder up the mountain. No rock has rolled back down yet, unless the mountains are elections.”

When it came to elections, he lost. It’s only in the final stretch of his career that Peres was showered with love. He became an admired and lauded president, a celebrated leader, the father of the nation and Israel’s elder statesman. When he closed his eyes for the final time, he had reached the mountain top.