The 'great awakening' of Israeli Ethiopian youth

After decades of discrimination and not fully integrating into society, many Israeli Ethiopians are returning to their roots, discarding their Hebraicized names and rediscovering their heritage.

Everyone has a name given to them by their parents, or in my case, my sister. My name, Ortal, was given to me my older sister simply because she loved the name. it was however rather bland, and as a child, I recall envying the other Ethiopian children who had Amharic or Tigrinya names.

I distinctly remember the time in high school when I signed my name on an exam as Mebrahti, which means Light in Tigrinya. It sounded a lot nicer to my ears than Ortal.

Many Ethiopian-Israelis have a birth name as well as a “new” name given to them by the Interior Ministry, school administrators or kindergarten teachers. Names are a symbol of our aspiration to integrate into the local landscape, to be part of the social fabric.

The State of Israel urged its immigrants to change, and they indeed accepted upon themselves the local pattern of names, language, culture and worldview. They accepted but they were not accepted in return. The disparity between them and Israelis whose skin is white can be felt in almost every aspect of our lives: education, employment, police brutality and even Avera Mengistu, rotting in Hamas captivity in Gaza.

But lately there has been an awakening among the Ethiopian community in Israel, they are returning to the practices of their homeland: weddings that are performed by Kessoch (Ethiopian clerics), reclaiming traditional ethnic names and a general Ethiopian cultural awakening.

Personally, I am a member of a spoken word troupe called Poetry of the Afro, which is now performing at the Hullegeb Israeli-Ethiopian Arts Festival.

The festival, led by artistic director Effie Benaya, is held at Jerusalem’s Confederation House and is now in its eighth year. And part of the festivities is a three-cassette set of Ethiopian Kessoch singing the Beta Israel prayers, collected over three decades. The audience’s craving to hear and see themselves reflected in the text was immense.

Former soccer player and Netanya city council member Imaye Taga, aged 33, has abandoned the name Amir, and returned to his birth name. Married with three children and studying for a degree in law, Taga has become a well-known social activist.

“The name is Ima-ye, like ’little momma,’” he explains. “But my mother says it means eternal child. I had an epiphany; I was sitting alone and thinking to myself: who gave me this name Amir? How did I, with such ease, let go of the name given to me by my parents?! Our names have a lot of meaning. And then I understood the level of insult towards my parents. So I went to the Interior Ministry and changed my name back to my given name.”

Were you criticized?

“Many journalists wondered how can I not feel part of general society, as I played for the Israeli national team. But that didn’t matter to me, it was one of the most significant things I ever did.”

What is the source of this trend of going back to your roots, which includes traditional dress and Ethiopian customs?

“In my view it is an outcome of the protests against police brutality in 2015. We tried to be accepted into mainstream society in every way and members of the community got sick of begging for recognition. This is how we are, like it or not.”

Today, Taga says that the there is still no change in society. “Police brutality still exists and open racism has increased. When you lose your trust in the establishment, you begin to do things yourself. I see the children, even those born in Israel, beginning to explore their identities and ask their parents about it.”

Kess Semai Elias, Director of the Spiritual Council of Israeli Kessoch, says the new movement is spreading. “When I was certified, there were a total of 60 Kessoch in Israel; today there are more than 30 newly certified young Kessoch.”

Semai says there are a few reasons for this, not least the rejection by established institutions, including the religious ones. For example, the Judaism of Ethiopian Jews is doubted by the Israeli Orthodox Rabbinate, which rules religious life in the country.

“Today more people recognize Kessoch,” he says. “We receive positive feedback and respect. I have been asked whether I am Jewish or Muslim and received funny remarks regarding my hat.”

What difficulties do you face?

“There are those despicable Israelis who believe there are no black Jews. They say ‘you have to say thank you that you were brought here to an advanced country.’ I don’t take them seriously.”

Why is it important that there be Kessoch in Israel, which already has so many religious figures?

“The Kessoch are our heritage, we view our Judaism through them. Without them we are merely immigrants who have come to live better lives in a western country.”

There are some who take the idea of cultural autonomy even further; some would say too far. One well-known individual envisions full autonomy, even if most of the community is against it. Semai says that at all the protests, people tried so hard to integrate but “all we want is to not be beaten (by police). People think that everything that has transpired was by chance, but they should read the newspapers and see how we were spoken about in the 1970s.”

Semai speaks from a place of pain and of anger. “I dreamt that we would have kibbutzim of sorts, with an Ethiopian majority, but not just any Ethiopian, only those who accept upon themselves Ethiopian traditions and customs, like the Ashkenazi kibbutzim… Some friends and I want to go back to Ethiopia and build a Jewish community in Addis Ababa. Jewish communities around the world do not face the ordeals that we experience here in Israel.”

Don’t call me Hanna

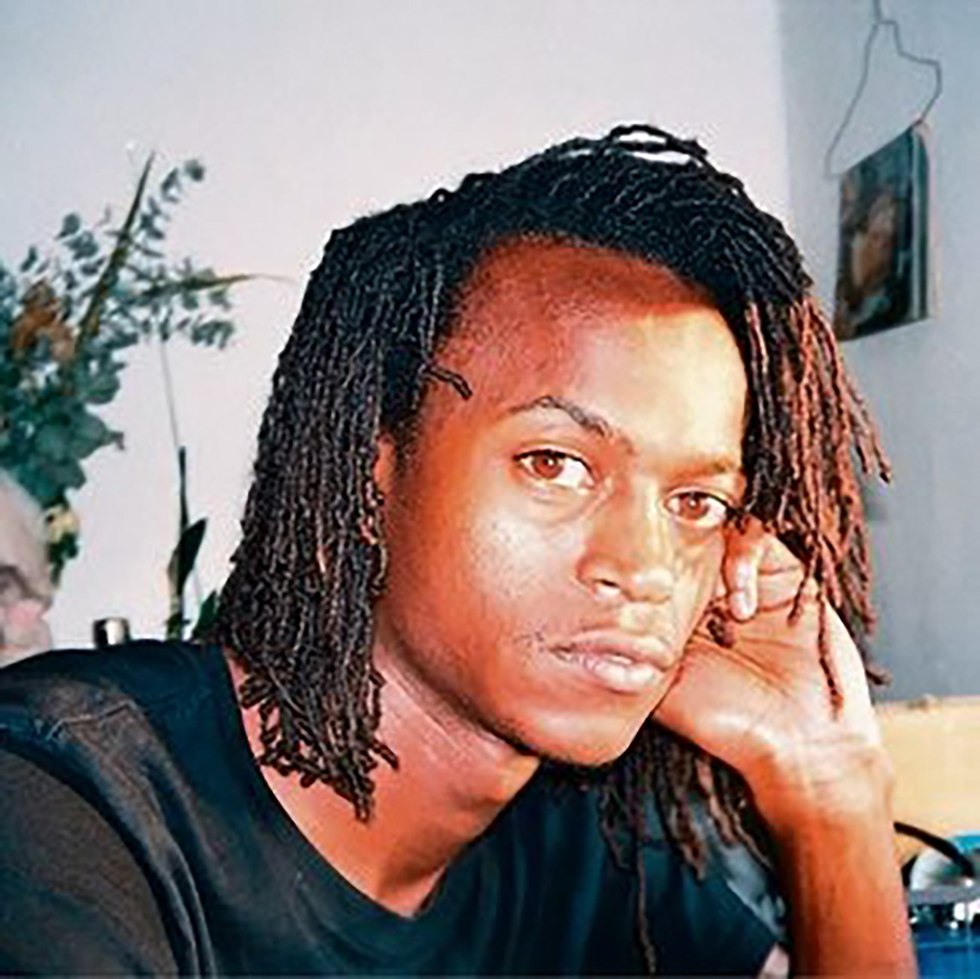

When I met 28-year-old Ashgar, an arts student at the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, I knew him as Danny. “I had an aversion to my name for a long time," he says,"and it affected my life, me as a person. I could not find myself and I felt it inhibited me and defined me in an unhealthy way. "

He was told that he chose the name Danny for himself, but he doesn’t really believe that. “At some point I found myself beginning to return to my culture, the Ethiopian community that I had abandoned as a child.”

When?

“From 2012 until the 2015 protests there was a great awakening. I felt that something was not right. I felt that I had to use my given name and be proud of it.”

Another catalyst for him was the death of his grandfather four years ago. “It really shook my world. When he passed I understood how much I was missing. The knowledge he carried, the family history, all the things that I ran away from as a child. My grandfather was also the only one who called me by my Amharic name.”

How integrated do you feel at Bezalel?

“I feel that I stick out. There are very few Ethiopians in Betzalel because these subjects (art) don’t figure into the consciousness of the community. But I choose to ignore that; I don’t want to be the token Ethiopian.”

Ashgar is currently participating in an exhibition titled Beta. “It all began in a Facebook group called Ethiopian Art. Its creator sought to create a platform for Ethiopian artists. People uploaded their creations and a dialogue ensued. The “Red House” in south Tel Aviv offered to host and ten days ago the exhibition opened. Everyone was shocked at how many people came. I exhibited two sets of photographs and I can’t wait till the next such exhibition.”

Nan (former name Chana) Bruck is a teacher, director and theater actress who runs Theatre in Color. It seeks to encourage people to discuss their personal identity and acceptance of others through the world of theatre. “In 9th grade I made a documentary about what it means to be an Ethiopian and it raised many questions about my place in the world. For example, why am I still using my new name given to me by the Jewish Agency?”

The name Chana still appears on her ID card, but Nani has moved on. “It is there to remind me that I have been through a process,” she says. “When I met Ethiopians who kept their original names during my military service, I felt jealous. When they began calling me Nani I felt as if some part of my being came alive again.”