The secret story of Israel's transit camps

In the early years of the Jewish state, new immigrants were sent to 'ma'abarot', tent cities of Jews from all over the world; conditions were tough and while many of the officers policing these shanty towns grew up there themselves, when the reisdents rioted, they were met with a firm hand.

Hundreds of tents sway to and fro in the cold wind; heavy rain pours down on them, and there is only mud underfoot. The new immigrants spend days waiting in line—for the shower, for the bathroom, for food—stripped entirely of any modicum of privacy. To ensure no one leaves the migrant camps or the ma'abarot (1950s Israeli transit camps deemed a step up from the migrant camps), the Israeli government instructed the police in 1949 to establish the "camp police."

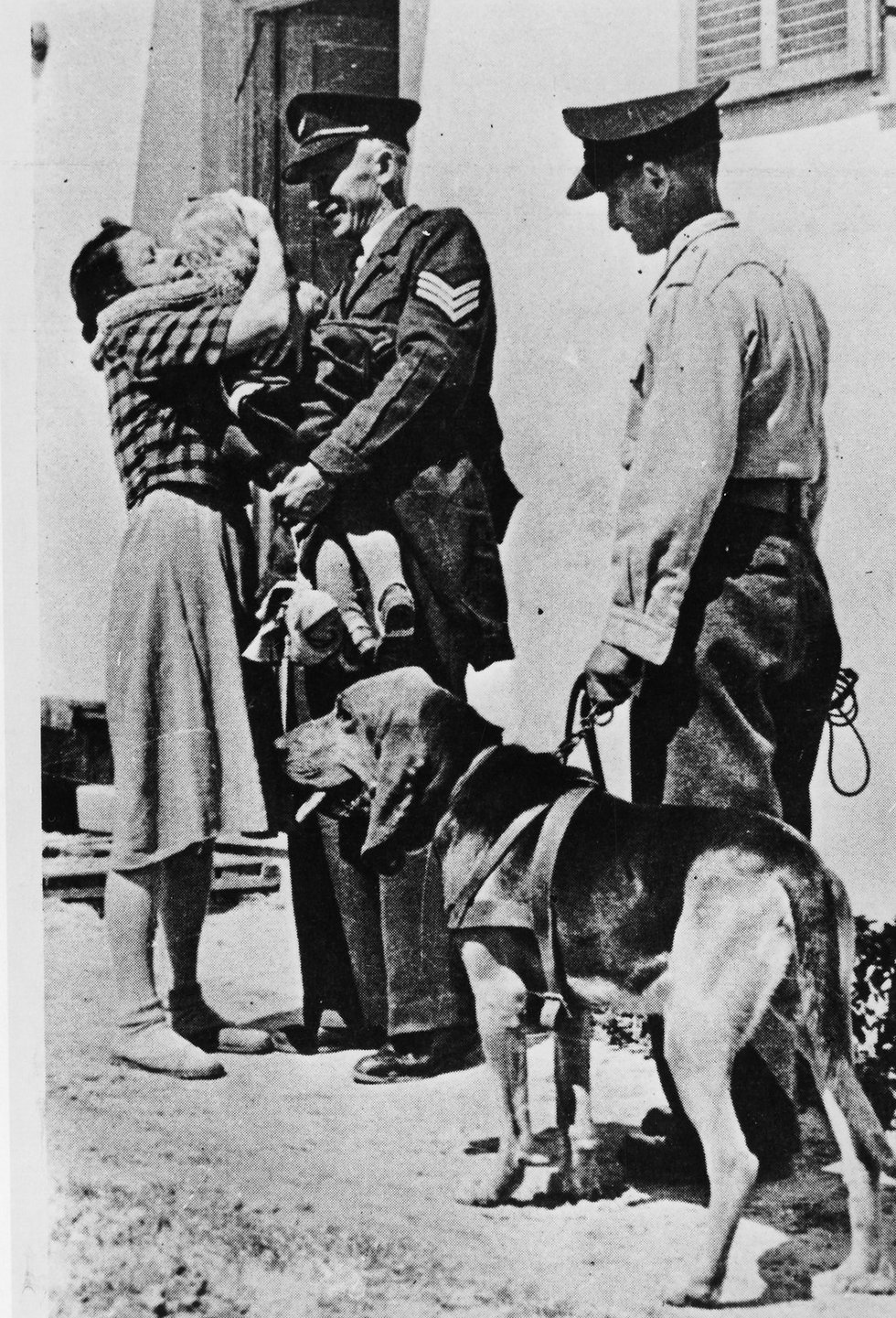

The immigrants' camps were surrounded by fences. Several hundred officers were guarding the ma'abarot, mostly to ensure the immigrants don't leave unsupervised or independently search for housing solutions outside the ma'abara.

The police force worked in conjunction with the Jewish Agency's Absorption Department, which was responsible for the upkeep of the transit camps' fences. "We asked the police to take on the management of the detention of the immigrants, which is necessary both for medical reasons and to provide the new immigrants with direction," the head of the Agency's Absorption Department, Giora Yoseftal, wrote to the Israel Police in 1951.

Deputy police commissioner David Nachmias raised questions about the prolonged detention, as the detention of immigrants in fenced-off camps, supervised by police, led to harsh criticism both in the media and from the public.

In a parliamentary question, MK Ya'akov Meridor wrote: "Is the honorable minister aware of the fact the immigrants' camp, in their appearance, give the impression of concentration camps? Does the honorable minister not believe that it is beneath the State of Israel to hold new immigrants behind barbed wire fences?"

"The Ma'abarot children stole food, and stole fish from the farms of nearby kibbutzim," Eden says. "In Tiberias, they fled to the beach on Fridays and stole food from people who came from Tel Aviv to spend the weekend on the shores of the Kinneret. The children were hungry. My commander told me, 'You're not a social worker,' but it wasn't that simple for me. Often I would give children the sandwich I brought from home and bought tea for them from the kiosk. I saw that they were simply hungry."

"I couldn't be mad at them; but I did open criminal records for them and took them to court. Parents would often encourage their children to steal a second and third time, because they knew that on the fourth time they would be sent to a home—where they would receive food, housing and education paid for by the state," Eden says.

Did you understand where they were coming from?

"I too stole food. In the ghetto, if you didn't steal food, you died. I don't even remember what we ate. On the day of liberation, I went with my brother outside the ghetto walls, and we found a basement that had been looted, but inside we found cocoa. I took off my hat, and with my hands I collected cocoa off the floor and brought it to my grandmother. She cooked it with water—no sugar or anything. But believe me, it was the best cocoa I ever drank."

Eden was 10 when the Nazis sent his father to a labor camp. "I never saw him again. I was 11 when they took my mother, and I never saw her again either. I survived the ghetto alone with my brother, who is three years older than me," he says.

The memories of that hunger, which was so bad his stomach twisted in pain, will never leave him. "I would go on entire day without eating; we would eat snow in the freezing cold," he remembers.

Levi made Aliyah to Israel in 1948, served in the IDF and joined the police upon his army discharge. He received a 1.5-room apartment in Beit She'an, where he lived with his wife and their baby.

"There was a massive ma'abara there. The residents kept changing," he says. "First came the Iraqi Jews, who lived in tin shacks or huts. When they moved to apartments, came the Moroccan Jews to replace them. When they left, the Yemenites came, and finally the Persians."

"I mostly saw the Yemenite children; this is what has been etched into my memory. They reminded me of the survivors of concentration camps; they were skin and bones. When they were brought to Beit She'an, social workers came and took them to the hospital for treatment. When they were returned to the camp, their parents could hardly recognize them. They left in a skeletal state and when they came back, they were thriving.

"Some of the parents also moved to other camps—for example, one family went half to Beit She'an and half to Afula. (The social workers) tried to call them when the child was in hospital in Afula, but when they brought the kids back after three weeks, the parents were no longer there, so they were taken back to the hospital. I am guessing—but it can't be proven—that some of these kids are the ones being searched for to this day."

This is Levi's version, based on what his saw with his own eyes while serving as a policeman in the camps, of one of the most painful wounds in Israeli society today—the disappearance of Yemenite children.

Years later, Levi finished a doctorate's degree in social work. "I went to work as a probation officer and ran the juvenile probation service in Israel. I have 12 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. I won," he says.

Fear and frustration

The story of the immigrants' camps and the ma'abarot will be told in a new docu series over four episodes on the Israel Public Broadcasting Corporation (IPBC), Channel 11. The series, "Ma'abarot"—which was created by Dina Zvi-Riklis, Shay Lahav, Arik Bernstein and Hila Shalem Baharad—is based on archive materials that have yet to see the light of day and interviews with dozens of immigrants who arrived in Israel at the time. The show highlights the massive gaps created between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi Jews in the early days of the state. It allows a filter-free look at a time that shaped our society, through the eyes of the new immigrants who arrived to the Promised Land from eastern countries. And, of course, it also deals with the feeling of discrimination and racism that remain with us to this very day.

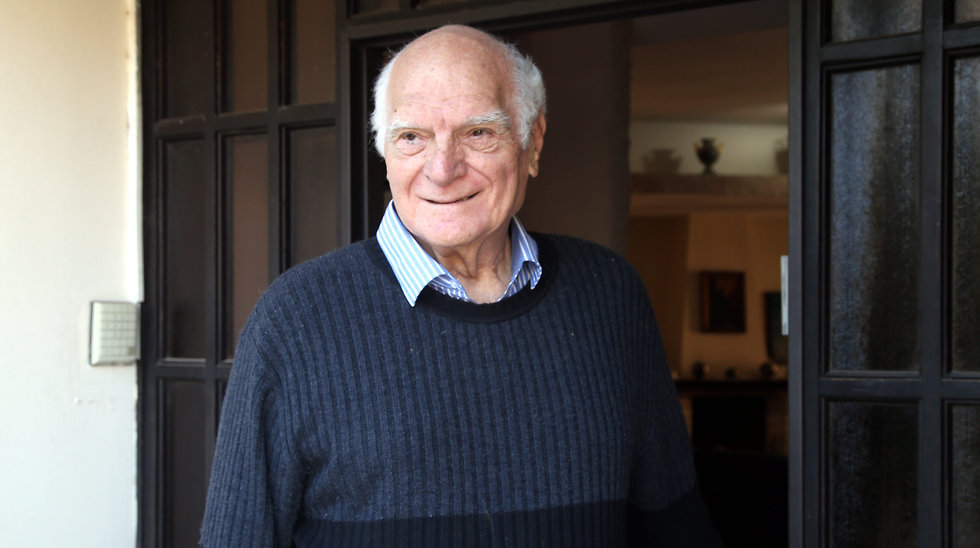

Criminologist Abraham Hemo, 85, who also trained Israel's national basketball team, immigrated to Israel from Egypt and was sent to a camp in Pardes Hanna. When he grew up, he too became a police officer in the camps.

"If you're asking me whether there was criminality in the immigrants' camps and the ma'abarot, the answer is yes. The interesting question is why," Hemo says. "There are several types of criminalities: one derives of frustration, another of absence—I steal because I'm hungry—and the third has to do with fears and anxieties and the desire to escape into drugs and alcohol. At that time, there were many crimes of the first two types: people were frustrated because they were cooped up in camps and couldn't leave. Boredom intensified, and they would fight all day—among them and with government representatives. There was also violence between neighbors and inside the family. Both adults and children at the immigrants' camps would steal, but not from each other—they would sneak through the fences and steal from nearby towns. There was also prostitution—women who didn't have any food sold their bodies for food and clothing."

"In the 1950s, close to 300,000 were absorbed into the camps and the ma'abarot. The crime rate in the ma'abarot was higher than its rate among the general population," he says.

"There are four main reasons that cause a man to commit a felony. The first has to do with the person himself and his personality. Others have to do with family and friends. In the camp, everyone lived together. If the family turned to crime, that was the model and children would learn from their parents. Another reason is the environment people lived in. The harsh conditions led people to lose control. Many people escaped because of fear and frustration—people were depressed, slept for 12 hours a day. A lot of people were hospitalized or fled to the big city. There were a lot of cases of suicide as well. People would jump in front of trains, take pills, suffocate themselves," Hemo says.

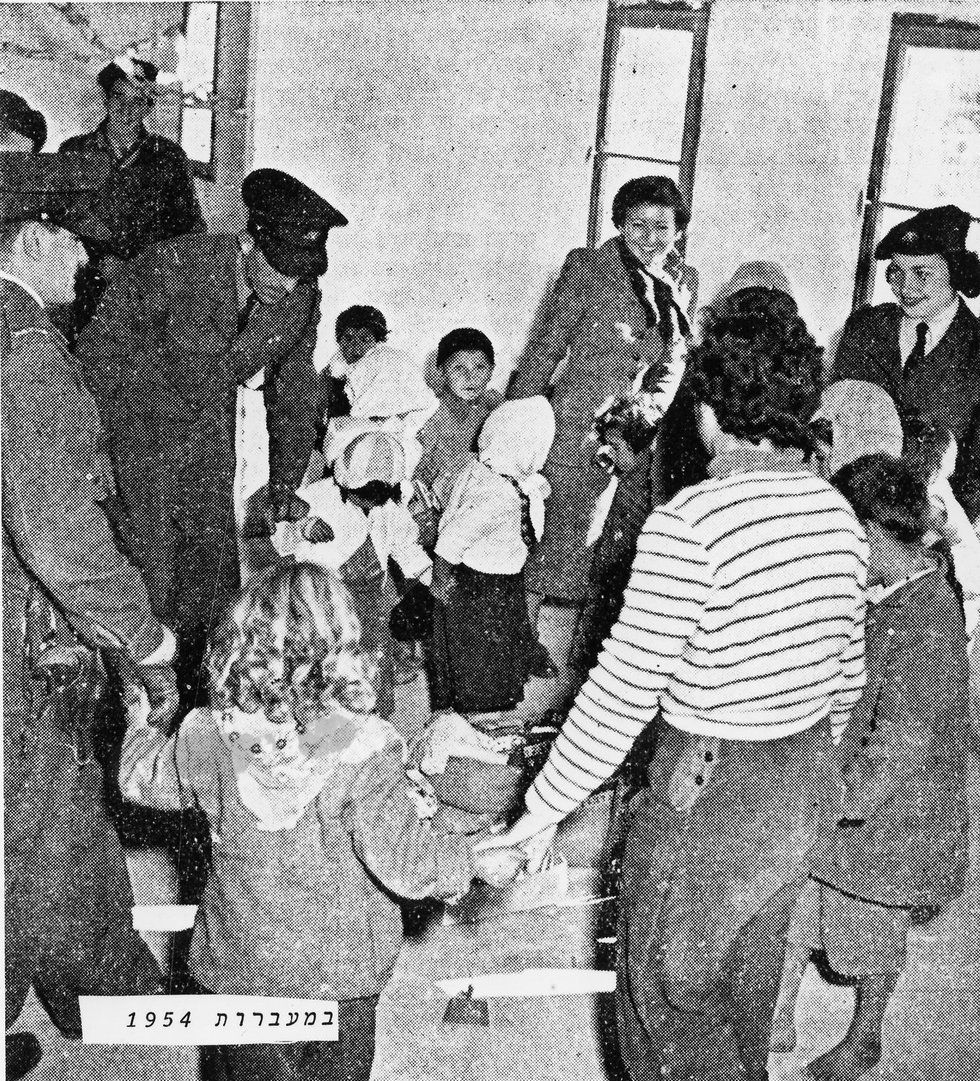

All of the new immigrants who arrived in Israel came through the Haifa Port to Sha'ar HaAliya, an immigrant absorption camp. "People would sit for three, four and even five days in tents waiting to be sorted. The first ones, who got special treatment, were the ones the representatives of the kibbutzim chose," Hemo says.

"Families that had at least one person who could work would be sent to the ma'abarot, while those who were left were sent to the immigrants' camps, where they were provided for, given a tent and buckets, and put in detention," he says.

"I was 15, the only adult in the family. We lived in a tent, and we had beds from the Jewish Agency. To stop the bed frame from sinking into the mud, we'd take canned goods and put them under the bed legs. In the morning, we'd move the beds aside and live in what was left of the tent.

"The mothers were busy all day with laundry, cooking and cleaning. The fathers who didn't work were frustrated and families fell apart. Luckily, I was an athlete, a basketball player for Hapoel Haifa. I'd wake up at 5am, go to work in construction in Hadera, and in the afternoon I'd get a bus to go to practice. I'd come back to the tent at 11pm," he says.

During his IDF service, Hemo served in the Golani Brigade, completed the commanders' course, and kept working to provide for his family. When he was discharged from the army, he joined the police.

"Our course was in 1955, there was massive rainfall and the entire Kordani camp in Kiryat Haim was flooded. We had to help people, get them out of the ma'abarot. Over the years, you erase the difficult memories, but thinking back, it was very difficult for the residents. All of the people we see fleeing the fighting in Syria and living in refugee camps—it was exactly like that. The fact people survived it and got out of there is a true miracle."

Tell me about your work as a police officer.

"As police officers, we would often provide assistance at the ma'abarot. There were always tragedies as well: diseases and criminality. There were always disputes between people from different cultures. There was a mixture of Romanians, Poles, Egyptians, Iraqi, Kurdish, Persians and Yemenites. Each and his culture and worldview. There were religious alongside the secular; there weren't separate synagogues. We had to maintain order and investigate offenses.

"However, the police officers were softer. I, and many other policemen, came from the immigrants' camps, so we were already merciful. At first I felt like I was acting as a merciful volunteer, not a police officer. Most of the police officers ... when our shift was done, we didn't go home, we stayed to help ... we weren't acting as police."

But there were also cases of violence, protests and arrests.

"During the Wadi Salib riots (in 1959, when immigrants rioted following the shooting of a Moroccan Jewish immigrant by police officers), it was very difficult. In this case, we acted as police officers and had to arrest people. But in the ma'abarot, even if we saw someone stealing—so what? He stole because he was hungry. We were forgiving. We always remembered where we came from."

Still, this time was—for many parents, children and even grandchildren—a deep wound that won't heal; a dark time of racism and discrimination.

"I don't agree with this assessment. I have a wife who emigrated from Europe with her parents when she was four. We at least had the ma'abarot; someone to give us food. They didn't have anyone to give them anything. No one was there to take them in. At the ma'abarot, there was someone to give you blankets, beds, food and work. There are people who went through a different kind of hell.

"In addition to that, I think the ma'abarot made people stronger. People who grew up in the ma'abarot and immigrants' camps and worked hard became stronger. Not all of them; there were those who went downhill, and for some that wound remains through the generations. But in general, we should also give ourselves a pat on the back."

'We lived hand-to-mouth'

Tzadok Malichi, 80, emigrated with his family from Yemen when he was nine. "I went through four ma'abarot," he says with a smile. "I started in Rosh HaAyin, then moved to Beit Lid, Tiberias and finally to Emek Hefer. I served in the IDF for 22 years and was discharged with the rank of lieutenant colonel," he says with pride. After his discharge from the army, he began working as secretary of a workers' council.

Malichi remembers the hard life in the ma'abarot, the food shortages and the hunger. "We ate what we were given. Father worked in public works projects for the unemployed for 10 days a month. Mother worked in housekeeping. We lived hand-to-mouth. We'd buy bread and margarine and sometimes add some jam. And this is how we lived and grew up."

Do you remember the police officers?

"I remember one incident in particular. There was one woman who went to get grass for her goat for Shabbat. She took 2-3 oranges from the nearby moshav as well. The moshav's guard caught her and set his dog on her. The dog bit her. Her son came back from the army that day and found his mother wounded in the hospital."

The son gathered some of his friends from the army, and the group beat up the guard and killed the dog. "I saw this with my own eyes, they gave the guard quite a beating, they wanted to kill him but decided against it," says Malichi.

"The guard filed a complaint with the police, and then cops were sent to find whoever beat him. The cops went into the camp with a vehicle on Shabbat, and the Yemenites came out of the synagogue. They each got a stick from the fences, smashed all of the mirrors and windshields of the police cars, and beat up the cops. Later, everyone went back to the synagogue to pray.

"At night, cops from all across the country came—close to 800 police officers—and each was stationed next to a hut. In the morning, they arrested anyone coming out of the huts that appeared younger than 17 and matched the description given by the guard. They put the detainees in a lineup, but the police officers didn't recognize anyone."

Just like many Yemenite families, Malichi had a cousin who disappeared. "His name is also Tzadok. I don't think it was planned or coordinated or government-sanctioned, but hundreds of children were kidnapped," he says.

"It's a wound ... I understand the outrage and the pain. If someone from northern Tel Aviv had their child taken, he would've moved heaven and earth to find him. There are people two years younger than me who remember having a little brother or sister taken. It's a stain to this day; it cannot be erased."

Fires and arsons

Prof. Sami Shalom Chetrit, the head of the School of Audio & Visual Arts at Sapir College and the author of "The Mizrahi Struggle in Israel," points to the motifs of oppression, resistance and protest in the immigrants' camps.

"At first, there may have been rioting, but very quickly fences were put up and guards were posted," he says. "It's important to understand where this is coming from. There's a large public living in the ma'abarot, a public (first Israeli prime minister David) Ben-Gurion later needs to integrate, but right now they're in the camps, living in tin shacks, huts, tents—people in waiting. This cannot be done without absolute control.

"There were very difficult sights; you could see Holocaust survivors looking through the barbed-wire and finding themselves on the other side of the fence, with Jewish guards watching them. A person who just went through hell finds himself in front of a Jewish soldier with a rifle. I'm not talking about entire organic communities, like the ones that came from Iraq or Yemen. People come in who lost their entire family in the Holocaust; they realize in a moment that they no longer have control over their lives.

"Ben-Gurion wanted to control every move, so there were very strict rules—including curfew and exit and entry permits. The communities lost everything; they lost control over their own lives. Not only were they unable to make a living, someone else was giving them food, and they were dependent on him. Overnight, they became refugees. It led clashes, and police officers used force to disperse protesters. There were many situations in which the flames rose too fast. There were arsons of tents; there was even a demonstration when a man was shot and killed."

Chetrit described the harsh responses to the immigrants' protests. "They were denied medical treatment, their power would be cut off. In one case in 1953, (Israel's national water company) Mekorot cut off the water supply to a camp near Rehovot. When several cases of dysentery were reported, the doctors refused to treat the patients, because they hadn't paid fees to the Histadrut labor union. They received punishment upon punishment," he says.

One of the gravest insults, he says, was in 1952 when, on top of the difficult conditions, some immigrants received preferential treatment. "They decided to stop the emigration from Morocco, after they found out (the Moroccan Jews) incited the most," Chetrit says. "That same year, the residents of the ma'abarot found out their neighbors, the Romanians, were disappearing. They were put in houses. It pained people that their neighbors received preferential treatment over them, and they had to wait years for their turn (to receive housing). They weren't blind; they could see what was going on."

"There was a convention (among Israeli authorities) to remove the Europeans from the camps as quickly as possible, and some of them were sent directly to permanent housing, unlike the Mizrahi Jews. It just added insult to injury. It all accumulated and led to the large Wadi Salib riots in 1959."

The police, he says, did their jobs. "The order to confine the residents to the ma'abarot and camps came from the government. The police took a firm hand against them: they had to disperse rioting, protests and hunger strikes every day. We're talking about food shortages. People see themselves living another year in these conditions, without food and with meager work, while the dream of redemption—we came to the Land of Israel, the ingathering of the exiles—was shattered.

"The Mizrahi families came off the boats wearing three-piece suits, ceftain they would be witnessing the return of the Messiah, and every day the dream was smashed into more pieces. This has been passed down through the generations."