In her shoes

Tami Arad, wife of missing aviator Ron Arad, grants her first interview in 16 years; speaks of the longing for her missing husband, the last letter he wrote, being a national symbol and the fact that life does, eventually, go on

Tami Arad has no sense of direction, a fact made evident when she contemplates aloud where we should meet, making sure it is away from prying eyes.

She knows giving an interview mean an exposure of sorts, but a habit of a lifetime cannot disappear in mere minutes. I suggest a coffee shop, but before I can give direction, she hurries and says "hold on a minute; tell Yuval how to get there." And off she goes, calling for her daughter. "I can't get anywhere without her," she says in a semi-apologetic tone. "She's my navigator."

We're both stumped. She knows, of course, that in the long and complex world of associations that make up Tami Arad in our collective mind's eye, "navigator" is probably the first one to come to mind.

Tami Arad has been in our lives for over 22 years. Ever since her husband, Lieutenant-Colonel Ron Arad ejected out of his F-4E Phantom Air Force jet into hostile Lebanese skies in 1986. He ejected because of a mechanical problem, which sent the Phantom – complete with heat seeking missiles, Volcano cannon, hundreds of shells and two rocket-propelled ejection seats – into a tailspin. That moment gave birth to the icon that is Tami Arad.

There is one image, one memory, she says, which took on a new meaning years after it actually happened: It was the day they first met. Arad's brother, Chen, invited her over "to meet someone." She arrived early and waited on a swing in the family's back yard. There was a floodlight on the roof, pointed straight at her. She sat there, like a deer trapped in the headlights of a car and Ron was inside, looking at her. A few seconds later, he turned to Chen and said "you were right." Ten minutes after she came into the house, she knew. Just like they always know in fairytales, or old black and white films. She knew he was the guy for her.

In many ways he still is, but he is out there, somewhere. "I'm a realist," she said. "I've never heard of anyone coming back from oblivion after 20 years."

The icon that came in from the cold

Last July, as part of the prisoner exchange deal between Israel and Hizbullah, meant to secure the return of Eldad Regev and Ehud Goldwasser's remains, Israel received the last few letters Ron Arad wrote. They were written during the first few months of his captivity – a 29-year-old man writing to his beloved 26-year-old wife and his baby girl. A 47-year-old woman was the one opening them, ever so carefully. By now, the baby is in law school.

It has been 16 years since her last interview. Sixteen year ago we didn’t have cell phones, laptops, Channel 2 television or a city called Modiin. Sixteen year ago Jacqueline Kennedy was still alive. The same Jacqueline Kennedy who was scorned by an entire nation when she dared wed Aristotle Onassis. Her nation knew she was a young woman, that no one prepared her for the day when a crashing warplane – oops – a 6.5mm bullet, would blast its way into her life. Nations are not quick to forgive their icons when they suddenly try to reclaim their lives. They wanted her to remain frozen in time; forever standing by his coffin, a black vale covering her face and her three-year-old son beside her, saluting his dead father.

Tami Arad is still assessing, anxious, the price of coming in from the proverbial media cold. She knows we prefer her to remain exactly where we left her – the widow that isn’t one, the child forced to raise a child on her own. Our collective memory has encased her in a glass bell, as if she herself were captive.

And one day you just decided to snap out of it?

"Yes."

In just one day?

"It was a process. After seven years the (Defense Ministry) called us and said they had reason to believe he was dead. Some Iranian ambassador station in some European country apparently said something to that effect. A few weeks later, they called us again and said the whole thing was a mistake. I couldn’t go on like that."

So you just went silent?

"One day I got a call from a woman who said she was the cultural administrator for a kibbutz up north, and would I consider giving a lecture. I didn’t understand at first, so I asked – 'You want me to come in and talk about myself? About Ron?' and she said yes. That was the moment I realized that being 'the captive navigator's wife' became my career."

So you quit?

"I put myself in the witness protection program."

Oh, but what a lecture that could have been! They would have been mesmerized. She would have been the talk of the mess for months. She could have led with the three years she spent living in their apartment in Ramat David (Air Force Base), with Yuval screaming in her playpen, the dog waiting by the door and her – constantly crying, drinking too much coffee, pencil thin, jumping every time the doorbell rang, losing sleep. "I was afraid to sleep, afraid to dream of him," she could have told them. "So afraid to lose control I never even dared take a sleeping pill."

Did you?

"Never. Not a single sleeping pill or sedative."

So you never lost control?

"What is 'losing control?'"

I don’t know.

"Is wishing you were dead losing control?"

Yes.

"Then I did."

And you did nothing about it?

"I had my little breakdown, but I never faltered on getting up in the morning and taking Yuval to school. I never asked anyone to 'take her for a while because I need to be by myself, I'm going through a rough time.' Not even to my sister-in-law, not to Ron's brothers, who were always there to catch me when I fell.

"I stayed up at nights, waiting for letters. I knew Uri Lubrani (former government pointman on captive soldiers) was on his way. I sat up waiting for nights on end, and I couldn’t even say anything to anyone. It's top secret. And he didn’t come. And I was all alone, with a baby."

Out of the cocoon? Tami Arad (Photo: Michael Kremer)

Asking the impossible

Maybe she is asking us for the impossible. Maybe, that safe place she retreated to for the past 22 years, has blinded her to the way all the lines have been crossed: To the images of a severed leg peeping from under a bloody ZAKA sheet in a Tel Aviv suicide bombing; or that of a red suitcase being pulled out of the Yarkon Riven with the remains of five-year-old Rose in it, splattered over three TV channels simultaneously; or those of New York's Deputy Fire Marshal Bill Feehan, chasing a photographer trying to get a good shot of people plummeting to their death from the blazing Twin Towers on 9/11, yelling "Have you no decency left?!" at the top of his lungs, moments before the east tower collapsed and buried him under it.

The question remains, what could possibly rival the defining moment of her life, which became one of the defining moments of our lives?

How much of him do you remember?

"A lot of things are fading away. His picture hangs in the bedroom, but he's young and cute and that was a long, long time ago. None of us look like that anymore. Everything fades with time. His smell, his voice… there is nothing you can do except…"

She pauses. Except what?

"It hurts. This is what really hurts. This is how you really lose someone, because of the years that pass by."

Tami Arad without Ron Arad is like Moshe Dayan without his eye patch, or Beethoven with two good ears. It is intriguing because it gives you the sense that there is another person hidden inside; Prometheus, bound to the rock of our existence, fighting to break loose of the chains.

She arrives to our second meeting with a bunch of papers.

"Here," she says, "It's your story about me. I wrote it for you."

You're that scared?

"Yes."

Why?

"I keep feeling guilty."

What for?

"For being alive even though he's not here."

Shadow of a myth

The story she wrote is not really a story, so much as a statement of defense: "My decision to fall off the public radar was not a conscious one. As far as I was concerned I was fighting for my sanity, because emotionally, I felt like I couldn’t take it anymore.

"I took Yuval and we went to the US for a year. It was horrible. The loneliness was even greater; but I needed that timeout to realize you cannot escape yourself. So we came back. To our family and our friends, who have been and still are my supporting circle. The media respected my choice. I think that when you send a clear message it comes across. With the exception of a handful of cases, they didn’t bother me and I appreciate that very much. Over the years I came to realize that it was the only way I could keep sane."

Not that she – or anyone else for that matter – knows what "sane" is under such circumstances. Everything in her life has to do with Ron. In a country long lost in its own sense of righteousness, who is to say where the lines are drawn? Is she allowed to laugh in public? To write a controversial article? To have a baby? To fall in love with the only man not daunted by life in the shadow of a myth?

How does he live with it?

"He doesn’t live with it. He lives with me."

And with IT.

"That's the last I'll say on the matter."

Looking back, do you think you made the right decision?

"After we got the letters from Ron last summer, I was even more convinced of what I had. He wrote that the love we shared gave him the strength to go on. That was my answer. He trusted me to raise Yuval properly. I did my best. I've made my share of mistakes. Who hasn’t?"

And now what? Will this be the moment when the horsemen of media apocalypse charge on their motorcycles, digital cameras in hand and brazenness as their armor? Or is there another option, one which suggests we still have a shared sense of decency left, and that after 22 years, we can let Tami Arad stop being TAMI ARAD for just a few moments?

The fact that she looks practically the same doesn’t help. Arad is one of those women barely touched by the hands of time and anyone who lived here during the 1980s would instantly recognize her.

They got married when she was 21.

"I was the one to propose," she boasts. "My parents were just divorced and my brother just got married, so I proposed to Ron."

What did he say?

"He laughed and said 'Isn't the man supposed to propose?' so I said, 'Fine, you propose.'"

Did he?

"We were married from the first day we met, when I was in the 12th grade. Besides, everyone in the squadron got married when they were young."

Karnit Goldwasser did things differently.

"Define 'differently.'"

She was able to make the world understand that she was a keg of gunpowder and that we better do something before she explodes.

"True."

You didn’t.

"We're not cut from the same cloth."

Meaning?

"Karnit learned a lot from our case. She pulled all the resources to end her nightmare as soon as possible. She succeeded where I failed, if you like. Udi came back. Ron didn’t."

Her message, basically, was "I don’t want to be Tami Arad."

"Yes."

Does that bother you?

"I'm fine with it."

She also didn’t want to be left an aguna (the Jewish definition for a woman unable to obtain a divorce).

"I guess. That fact stopped bothering me the day I realized that the only solution for my legal status was declaring Ron dead. No thank you. Don’t use my status to declare him dead as long as you don’t know for sure. And believe me – they don’t know. Of course, it's easier to say that if we haven’t heard from him in 20 years than he must be dead. Case closed. We – and I speak for Ron's family as well – think he deserves a little more than 'Sorry, we don’t know where you disappeared to.'"

'Life doesn’t freeze'

Last June she reappeared for just a second, writing Prime Minister Ehud Olmert a letter which was attached to Noam and Aviva Shalit's, the parents of kidnapped IDF soldier Gilad Shalit, High Court petition against the 2008 ceasefire agreement with Hamas.

That letter, she said "was the closest I ever came to actually saying he was dead, or at least, I guess it came out that way."

But you didn’t.

"Life didn’t freeze. They go on and Ron didn’t come back. That's a fact."

Do you know anything about the conditions he was held under?

"They called him 'the object.' This guy, who was king of the world, and they're calling him an object."

They become objects. Gilad Shalit too.

"I think about Gilad often. Noam and Aviva too. I told them that. As far as I am concerned, when Gilad comes back it would be beyond joy. I can't say it would be a comfort – there is no comfort and no forgiveness for what happened with Ron – but by having Gilad back I will have a sliver of the overwhelming joy that should have come rushing over with Ron's return. Gilad is alive and Gilad should come home. Anyone who has any doubts about any prisoner exchange deal should try substituting Gilad's name with that of their child. That will solve any dilemmas.

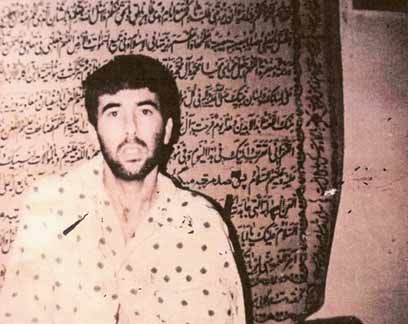

Arad in captivity

"After I read those few last letters, I realized they could only have been written by someone who's alive, whose life was taken away. The longing made it harder for Ron. I assume it's the same for Gilad. Secluded captivity like Ron's, like Gilad's, it's a path, like the tunnel people who have near-death experiences and have come back to life describe. The difference is that one is fully conscious in captivity and it is a very dark place. I don’t understand how we got to the point where Gilad has been held captive for over two years.

"This is a mind game. There are regional politics intertwined, naturally, since the Iranians have their hand in it. A lot of what was done for Ron was done too late. If we want to keep Gilad from drowning in an ocean of interests, we need someone with a creative mind heading the case."

There is no one like that.

"I was disappointed with Moshe Yaalon. In the few meetings I had with him when he was IDF chief of staff, I got the impression that this was a very moral person. It was hard to hear him talk about how sometimes we have to sacrifice soldiers. We sacrifice solders in every war – it is inevitable… (but) if someone survives that inferno and the State gives up on them 'because some interests are more important than one soldier's life' – than as I see it, we've lost one of our basic moral values."

Proportionate response

If the jet had not been shot down, where would you be today?

"In Rehovot."

Rehovot of all places?

"Ron wanted to work for the Weizmann Institute of Science. He was studying chemical engineering at the Technion in Haifa and he wanted to get his Masters' in genetic engineering."

And you?

"I wanted to have five children."

And what would you be doing?

"I don’t know. Maybe I would have become a teacher… I really don’t know. It's such a hypothetical question. You have no idea just how hypothetical."

I don’t buy that.

"Why?"

There it too much of a gap between you – the person you have become – and that description.

"I don’t know. I was so young; I really don’t know what, who I was."

Well, you didn’t become a teacher.

"Yes, but before… Ron was the bright one."

And you?

"I was with him."

And that was enough for you?

"I was just happy he wanted to be with me."

As horrible a gamble as it is, life is made up of the permanent tension between characteristics and circumstances. It is safe to assume, especially with everything that has ensued, that Arad was just not meant to be a teacher in Rehovot.

The 1980s ended with her going through the one photo album she had over and over again; she started writing a diary and scrapped it; she underwent therapy; read Catch 22 – which Ron left by the bed – over and over again; and she raised Yuval – or was it Yuval who was raising her?

The 1990s saw her become a different person. She kept fighting her losing battle, but she was invited to the Defense Ministry's building in Tel Aviv less often; meeting with the respective IDF chiefs - a distant, slightly embarrassed Dan Shomron, Ehud Barak with his never-ending Zen mantras, the ever-good listener Amnon Lipkin-Shahak; Shaul Mofaz, with his constant all-night pharmacist look and the somber Yaalon – each making promises they could not hope to keep.

The meetings led nowhere and she eventually found herself losing – to herself. She no longer had the ability, the strength to keep up the near-grieving widow routine. So she left the television studios to the tragedies de jour and slowly got on with the business of living, studying criminology and working with distressed soldiers before shifting gears, hosting a weekly radio show on a local station, writing a newspaper column.

It is almost ridiculous, but Tami Arad, our national absentee, has been corresponding with us constantly for all these years.

"In all my years of writing, I've almost never received any reactions involving Ron. Everyone thinks it's a different Tami Arad," she says, amused. Maybe it is because she sounds different. Different from what – I do not know – but different from what we might expect a Tami Arad column to read like.

The writing experience gave way to a three-year writing frenzy which culminated in her first novel. She struggled with the familiar pitfalls. Ernest Hemingway, her favorite author, said that writing was like architecture. Gabriel Garcia Marquez equated it with carpentry. Reality, she found, was harder than wood and tougher than interior design. Let's face it, said author William Styron, writing is hell.

This is not a biography, she stresses. The novel centers on a man – a neurosurgeon as cold and clinical as his profession – who wakes one morning to find his much-younger wife has a brain tumor. The novel is skillfully written and well researched. Her "visit" to the cardiothoracic wing is meticulously described and the history of the characters' love affair is presented to the readers frame by x-rayed frame; until we do what doctors are forbidden to do – we grow emotionally attached to the patients. But somehow, Arad's biography still hovers in the background.

"How did you come to that," she asks, curious.

You write about the fact that when something awful happens to a person, it also happens to their spouse.

"So?"

Isn't that what you have been feeling all along?

"No… absolutely not. I never saw myself as the heroine of Ron's story. I never felt that way, no matter how sorry I felt for myself. Maybe it would have been different had he been killed, but because he went through all of those horrible things there, I could always keep myself in check."

Was there ever a moment when you wanted to write your own story?

"(Writing) opened up wounds which bled even without me touching them. I realized that writing about myself wasn’t the way to go, so I reverted to fiction. I use my characters to live in a movie whose script I wrote. Now, I can see psychologists nodding their heads and saying this is my way of compensating for my lack of control over real life. Maybe it is. I don't know."

Yes you do.

"I am who I am. This is my name, for better or for worse, but my aspirations go beyond the role life has in store for me. Maybe 'aspirations' is too big a word; 'needs' is better. I'm not sure."

The book is dedicated "To my Ron," followed by a few lines form the Moody Blues' 1967 song Nights in White Satin: "Nights in white satin, Never reaching the end, Letters I've written, Never meaning to send…"

Why did you choose that song?

"It was his favorite."

That's all?

"The night he vanished, everyone was looking for his brother, Chen, who was in a movie. After he came out and they told him, he got in the car and turned on the radio. The anchor said that an Air Force jet was shot down. And then they played that song. Of all things – that song."