Jewish ghetto life, in color, from 'Hitler's photographer'

As part of his job as 'special military reporter,' Hugo Jaeger got to use advanced color photography during World War II. His work includes unique documentation of Jews in Warsaw, Kutno ghettos

The pictures were taken by senior photographer Hugo Jaeger, who received unprecedented access to the area and to the Nazi regime's upper echelon, including Adolf Hitler, and got to use the most advanced technology of that time – color photography.

The photos were released to mark the 72nd anniversary of the official establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto in October 1940.

In one photo from 1940, people are seen queuing for water and vegetables, under a sign reading, in German, "Typhus area."

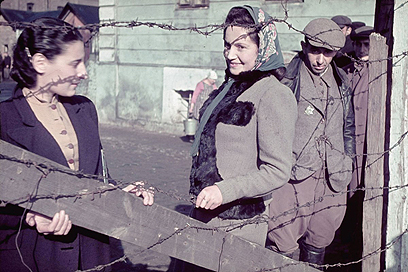

Warsaw Ghetto, 1940 (Photo: Getty Images)

LIFE magazine, which bought the photo archive from Jaeger, describes him as Hitler's personal photographer and has published photos he took during the Third Reich leader's 50th birthday in the past.

But Dr. Daniel Uziel, a historian from Yad Vashem who also deals with photos from that era, doubts the title, describing Jaeger as "a special military reporter" who received rare access to places regular photographers were no allowed into.

"Jaeger was a famous photojournalist in Germany in the 1930s. He was drafted at the beginning of the war as a reservist to the Wehrmacht propaganda units. Because of his status as a photographer he received the status of a special military reporter," explains Uziel.

"He was given uniform and weapons and received access to wherever he pleased. Because of his special status he also got two unusual photography technologies: Kodak color film and a stereoscopic camera which creates images in 3D. He would shoot the same scenes with both cameras.

"He was supposed to hand the pictures over to the Nazi propaganda office, and apparently never did. These photos did not pop up at the time."

Justyna Majewska, a curator at the Holocaust Gallery in the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, notes in an article on Time magazine's website that there is virtually no German military presence at all in the pictures.

Dr. Uziel explains that "the German army was preparing to invade the Soviet Union at the time. So in those areas, taking pictures and conveying information on the army were strictly prohibited.

"The propaganda units had nothing to do. They began looking for subjects and found the ghettos. This is the reason why there is series of newspaper articles, photos and films from that time showing the ghettos in Poland."

As opposed to other propaganda photos from that time, these pictures do not appear to be hateful or dehumanizing, although Jaeger is described in the article as an "ardent Nazi".

It is quite possible that Jaeger had asked the people for permission to take their photos, and thereby documented a young woman smiling for the camera in the Kutno ghetto in the Łódź province, a photo which stands out against the background of her miserable surroundings.

According to the Yad Vashem website, some 6,700 Jews lived in Kutno before the Holocaust, making up more than one-quarter of the city's population. The Germans set up the ghetto in June 1940, after many more Jews arrived from the area.

"The color photos don't seem to match the Nazi stereotype of Jews," explains Uziel. "The Jewish women are pretty, and they would usually choose ugly motifs. It doesn’t look like a propaganda photo."

The photo of the three made-up women was presented in Yad Vashem's "Spots of Light" exhibition, which describes the different experiences of Jewish women during the Holocaust and has been displayed around the world.

Jewish man and children in Kutno, 1940 (Photo: Getty Images)

Jews in Kutno Ghetto, 1940 (Photo: Getty Images)

Jaeger did not hand these photos over to the propaganda office, but he did transfer the 3D pictures to a German publisher, which was part of the propaganda systems and had a monopoly over this technology.

"They published fancy albums with empty spaces to glue the pictures in, like cards," says Uziel. "The thick cover had a pocket with a stereoscope, a device used to view these photos."

Jaeger's pictures were likely designated for an album on the war in the east, part of which was to be dedicated to the Jews. The album was never published, perhaps because of Nazi Germany's defeat.

- Click here to view additional color photos by Hugo Jaeger from ghettos

The Time article describes how Jaeger's 2,000 photos reached LIFE in the 1970s:

"On that spring day in 1945, during a search of the house where Jaeger was staying, the Americans found the leather satchel in which the Führer’s personal photographer had hidden literally thousands of color slides. What happened next, however, left Jaeger staggering.

"Inside the satchel that held the compromising pictures, Jaeger had also placed a bottle of brandy and a small, ivory gambling toy — a spinning top for an old-fashioned game of chance known by, among other names, 'put-and-take.'

"Happy with their find, the soldiers sat down to a session of put-and-take while sharing the bottle of brandy with Jaeger and the owner of the house where the photographer had been living. (Jaeger’s own apartment in Munich had been destroyed in Allied air raids.) The leather satchel, and whatever else was hidden away in it, was forgotten as the brandy dwindled and the game of put-and-take spun on.

"After the Americans left, a shaken Jaeger packed the color slides into metal jars and, over time, buried them in various locations on the outskirts of town. In the years following the war, Jaeger occasionally returned to his multiple caches, digging them up, drying them out, repacking and reburying them."

In 1955, he dug them up and hid them in a bank vault in Switzerland. A decade later he sold them to Life magazine.

Roi Antebi contributed to this report