Jewish myth: 50 years since Masada dig

What is it about site identified with Jewish heroism and sacrifice that has turned it into most visited tourist attraction in Israel?

It was first discovered in 1806, after being hidden for hundreds of years, but those who discovered it failed to understand what they had found. It was only in 1838 that American researchers Robinson and Smith identified the remains of the northern palace as Masada when they watched it through a telescope from Ein Gedi.

Another 125 years passed before Hebrew University and the Israel Exploration Society (IES), led by archeologist and politician Yigael Yadin and his team, uncovered the site which would later become identified with Jewish heroism and sacrifice.

These days, archeologists are marking the 50th anniversary of the start of the first Zionist excavation in Masada, a dig which turned it into center of attraction for tourists from all over the world, an American television series starring Peter Strauss and Peter O'Toole, and mainly a strong myth for thousands of Israeli youths who began "conquering" the mountain in the 1930s and 1940s.

Dr. Guy Stiebel is the modern excavator of Masada today, a job which he has been doing for almost 19 years now, together with the late Ehud Netzer, who was killed about three years ago while searching for Herod's grave at Herodium.

Among the archeologists who studied Masada in the 1960s and 1970s are some of Israel's best researchers, including Amnon Ben-Tor, David Ussishkin and Shmarya Guttman.

Stiebel talks about Masada like a man possessed. He is in love with every stone, detail or ostracon (piece of pottery) found on the ground. "The story of Masada is not black and white," he says. "When you remove the cover you discover a whole universe of small details: A little girl's toy, a Roman soldier's pay slip, and even the name of the baker on the site."

Seeing life, not death

Although the one thing everyone remembers from Masada is the mass suicide (which did or did not take place – depends on whom you ask), Stiebel prefers to see the life on the mountain rather than the death.

He walks through the museum at the foot of the site and passes through the archeological findings, getting all excited as if they were his children. Each of these findings has a story and a way of life behind it, and every finding is cherished and important: Round stones which were used for slingshots, the most ancient lice removal comb in the world, which even had a louse on it, and an ostracon with the name Shimon Bar-Yoezer inscribed on it in Hebrew.

The research of Masada never ceases. The great contribution of the recent years is in the material culture shedding light on what happened there. Who were the people? What groups lived on the mountain? What did they do for a living? For example, the baker who worked in Masada's big bakery, where bread distribution coupons were found in the form of broken clay pottery with the baker's signature on them.

Herod, Herod and Herod

But one cannot tour, think, understand Masada without its main figure – Herod. Otherwise, the top of the mountain, as beautiful as it may be, would have been just another part of Haatakim Cliff overlooking the Dead Sea.

So Herod is the man. You'll love him for his building enterprises in the country, or hate him for his cruelty towards his Jewish brothers – but Herod is the most important figure in Masada. Although he was not the first person to establish the settlement on the mountain (it was likely Jonathan Apphus, the brother of Judah Maccabee), he definitely left his mark on the place.

The omnipotent "constructor" built five palaces on Masada. The most famous and beautiful of all was the northern palace, where he lived like a king. What does it mean to live like a king during those times? It means bathing in his pool which had quite a nice view of the Dead Sea, eating food covered with fish sauce imported from Spain, and for dessert munching on apples which were also picked abroad. These findings were found in the remains left in jugs on the site. In other words, the man knew how to live.

But Herod definitely also knew how to kill. For example he executed his wife, Mariamne the Hasmonean, by hanging when she was 25, and the sons she gave him did not get to grow old either lest they rebel against him and avenge her death.

Blame it on the persimmon

Beyond Herod are those rebels who controlled Masada several decades after he passed from this world (in 4 BCE). The mythical story has to do, undoubtedly, with them and the days after the destruction of the Second Temple.

Those same groups of rebels, not zealots as commonly believed, arrived in Masada both because they escaped the horror of the Romans and because they sought to keep a unique secret – a secret they feared would fall into the hands of Titus' soldiers.

What is that secret? Well, money. And in this case the money does have a scent. Seventeen kilometers (10.5 miles) north of Masada, the people of Ein Gedi used to grow the persimmon plant (Commiphora gileadensis), also known as balsam (balsamum), which was used to create the best perfume known to the universe at the time, and the Jews held on to the secret to its preparation.

Discovered papyruses revealed that the Roman army traded in persimmon in Masada and earned millions of Sestertius (ancient Roman coin), worth millions of dollars today, from selling the expensive perfume.

'Masada was just another battle'

That, in Stiebel's opinion, is the main reason for the siege. "For them, Masada was just another battle," he says. The Roman army included a legion of 6,000 to 8,000 soldiers, who set up eight camps besieging the mountain, as well as a dike (siege-wall) encircling it. The siege lasted about two or three month, not more.

It was all directed westward to the great incursion, as they reinforced an embankment on which they placed a battering ram which broke the wall and sealed the fate of the entrenched Jews. Did they choose to commit suicide? According to Yadin, who laid the foundations for understanding Masada, there was indeed a suicide and he had found several skulls of those who killed themselves on the site.

In addition, Roman author, naturalist and army commander Pliny the Elder wrote that the Jews tried to destroy the plant like they did their lives, in other words – committed suicide Stiebel believes it was suicide too, as death in this form was common those days.

"It's important to look at this death through the eyes of that time," he explains. "It was either death by suicide or by the Romans, and so there was nothing despicable about it."

Flavius Josephus based his book "History of the Jewish War against the Romans" on Roman reports of the army at the end of the revolt, according to which apart from two women and five children – everyone committed suicide.

There is no archeological proof of suicide, however. The 11 ostraca found in a room with names on them are in line with what Josephus wrote, but still fail to confirm that they were indeed used notes for a draw.

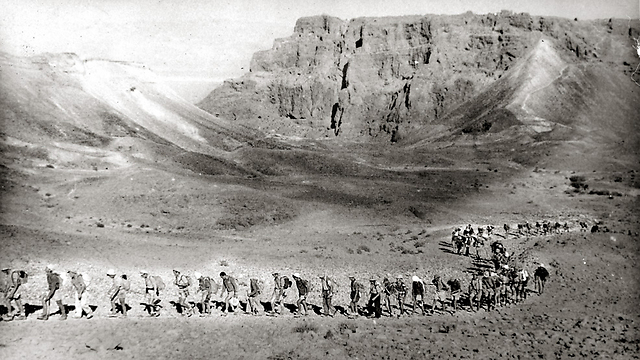

Volunteers arrived from all over the world. Yigael Yadin with team of researchers on Masada

Epilogue

It remains unclear whether the end of Masada was reality or a legend. In any event, geography teachers and educators have chosen to raise the next generation on this myth: That few can stand against many, that they don't give in, and on the belief that Masada shall not fall again.

The picture of the events which took place in Masada is still complicated and it will probably take another 50 years of research before additional details are clarified and shed light on what happened or didn't happen at the site.

Is suicide a heroic act or not? Every person can choose to see the ending as he or she wants. But Stiebel would like you to understand one thing: "What's important in Masada is not necessarily the death, but the life."