What's up for discussion when we talk about security

Analysis: Type of expertise NATO will turn to in order to make sense of new situation can come to define security for decades if it succeeds in becoming objectified.

A little more than 15 years ago the book "Security: A new framework for analysis: was published. The authors claimed to have observed how the concept ‘security’ functioned in political practice and provided a lens through which to understand these practices. The main idea behind the book was to argue that security could not be regarded as something substantial or universal. What mattered were political processes of securitization in which something is presented as an existential threat to e.g. a state, to world peace, or to a certain identity.

If accepted by a relevant audience (the population of a state, its elite, elders in a small community or the like), the process of securitization would lift the issue labelled a ‘security issue’ out of the sphere of normal politics and into a state of emergency in which a number of countermeasures – not following normal, democratic control and rules - could be legitimized. This was the logic of securitization. It therefore made no sense to have debates about whether or not threats to individuals or states were ‘real’ security issues. They were issues of security if a threat was mobilised as existentially threatening the future existence of a certain entity and emergency measures were suggested in order to contain the threat.

Since the publication of the new framework, the idea of securitization has travelled worldwide in academic circles. It seems to have been able to capture political processes surrounding security in an apt manner.

If looked at from the perspective of providing security expertise, securitization offers a grim predicament. Being a security expert becomes a dangerous endeavour, because not only may using the word ‘security’ in relation to e.g. ‘immigration’ or ‘climate’ create a link between issues not hitherto understood in security terms, which may pave the way for securitization of a range of new issues and emergency measures. The mere participation in media coverage or policy-preparing work on security issues risks leading to more securitization and illegitimate practices. Scientific arguments – or facts – can also be mobilised by other actors., because the objective, disinterested aura of the scientific vocation makes scientific explanations valuable as a type of power for practitioners: by drawing on the ‘scientificity’ of a statement, an argument suddenly carries more weight.

Looked at sociologically, scientific statements – such as the concept of securitization - can also gain a standing, which leads to closing off debates: Contrary to lifting issues into a problematic emergency sphere, objectivation pushes political processes into a non-political sphere of business as usual, which can be even harder to counter in practice. For security experts, this mechanism might prove even more difficult to juggle than the mechanism of securitization.

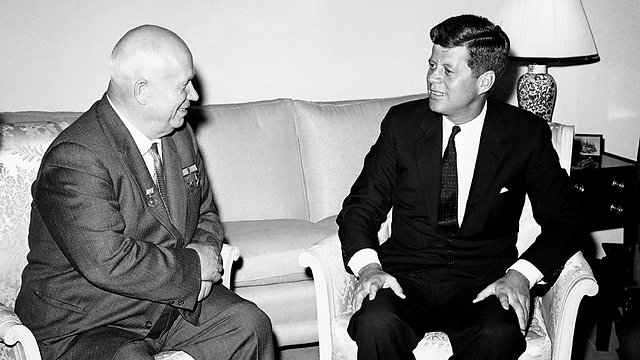

Consider this in relation to a well-known example from security theory. In the early years of the RAND Corporation, a group of researchers set out to explain the new security situation from a social scientific standpoint. Without any empirical evidence to support their findings (no nuclear war had been fought – thank God!), the group developed a thought-provoking and immensely influential view of how nuclear strategy should be performed. From these models policy advice was deducted and policy was formed. The necessity of nuclear deterrence was objectified. This had repercussions for e.g. NATO and a dangerous balance of power resulted.

In the aftermath of the Cold War, the old truths could no longer hold, however. Concretely, for NATO, this meant a shifting of focus from balance-of-power models in a conflict-ridden international system to ‘the future can be shaped’ types of arguments. This involved the mobilization of new types of experts and a set of new political practices for e.g. the NATO secretaries general: From having been focused on internal NATO business, the new Secretaries General – most strikingly Javier Solana (1995-1999) – reached out to universities and think tanks in an attempt to shape the strategic environment of the alliance. By 1999, Solana even stated that: “Indeed, had we listened to theory, we would not have come half as far. Theory told us that NATO Enlargement and a NATO-Russia relationship would be mutually exclusive goals. Practice proved otherwise” and that “Security in the 21st century is what we make of it. The future can be shaped."

These were important features of how NATO came to understand security in the late 1990s. And of course, it paraphrased the theoretical fashion of the day: “Anarchy is what states make of it”, every student of international security was taught, thereby indicating that the conflictual nature of the international system was a thing of the past. But interestingly, NATO seemed to replace the plural ’states’ with a singular ‘NATO’. ‘The strategic environment is what NATO makes of it’, the saying seemed to transform into, when it left the academic expert circles and was mobilised in a practical, political setting. And it seemed to become the truth about (Western) security for almost a decade. Social constructivism was objectified as a security strategy. Security was no longer considered a substantial issue, but a political practice with a malleable end-state.

With the Russian annexation of Ukraine, this truth seems countered. The strategic environment appears not to be as plastic as NATO’s version of the theoretical fashion would have it, and processes of securitization have arisen anew. NATO responded to the unexpected situation by cutting off all communication with Russia and securitizing ‘international stability’.

But if Russia struck Ukraine hard, anarchy struck back harder on NATO, so to speak. The objectivation of a certain version of social constructivism did not hold as a security strategy. The issue for experts in the future will therefore be to decide whether to understand the situation in terms of balance of power in a conflict-prone international system or as a reminder that a socially constructed anarchy is indeed what a plurality of actors make of it. In this version, securitization attempts will occur until a new, stable vision of the world has taken root - and expert voices will be voices in a game of securitization. No matter the outcome, the type of expertise NATO will turn to in order to make sense of the new situation can come to define security for decades if it succeeds in becoming objectified.

Trine Villumsen Berling is a post doctorate fellow at the Department of Political Science, 'CAST, Center for Advanced Security Theory', Copenhagen; and a research fellow at NATO Defence College, Rome.

This article was brought to publication as part of a cooperation between Ynet and the Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus.