Carving a memory

Shoah survivor Yitzhak Arad, who went from partisan to Palmach and upper echelons of IDF, has found a unique way to preserve memories of his loved ones who perished in Holocaust.

Dr. Yitzhak (Tolya) Arad has devoted almost his entire life to the good of the Jewish people, the State of Israel and the memory of the Holocaust. He was one of the anti-Nazi underground's most daring fighters during World War II, a member of the Palmach, a commander in the Israel Defense Forces, the IDF's chief education officer, an important historian, and chairman of the board of Yad Vashem.

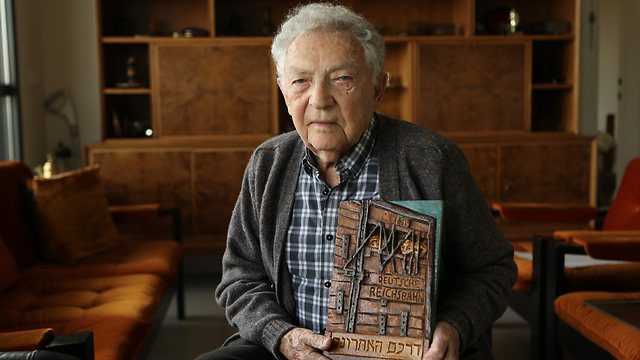

Today, at the age of 88, he has moved on to the project of his life – memorializing all the members of his family who perished in the Holocaust in wood carvings.

"When I moved into the Mediterranean Towers retirement home, I took a course in woodcarving," Arad says. "I started by etching Mordechai Anielewicz. I then etched figures of Jews on their way to their deaths on a train, and then I decided to focus on all the members of my family who perished in the Holocaust and perpetuate their memory."

Born in an area of Poland that is now part of Lithuania, Arad was in Warsaw at the start of the war, and he celebrated his bar mitzvah under German rule. "German soldiers were coming inside, cutting off beards and abusing the Jews," he recalls. "I suggested to my father that we forgo the bar mitzvah, but my father said: 'A Jewish boy does not forgo his bar mitzvah,' so we celebrated under the occupation."

A month later, Arad and his sister fled Warsaw and returned to their home town, where most of their relatives were living at the time, still under Soviet rule. His parents remained in Warsaw, hoping to be able to escape at the first opportunity. "But," Arad sadly notes, "they suffered the same fate as the remaining Jews of Poland – either they died in the ghetto from disease and starvation, or they were sent to Treblinka in the mass deportation."

In June 1941, the Nazis reached the town where Arad was living; and in late September, most of the town's Jews were taken for a "hike" into the countryside, where they were all shot and killed. Arad and some of his friends managed to escape on the way, hiding for several months in the region of Belarus and looking for partisans to join up with.

Unsuccessful, they returned to the town to find that only around 350 Jews still remained there. All were craftsmen whose services the Germans and their Lithuanian cohorts required.

Arad's private little miracle occurred one morning in 1942, when the Germans took him and his friends to sort through a cache of arms seized from the Soviets. Over a period of several months, Arad and his friends stole various weapons; and in March 1943, they fled the town and joined up with the partisans in the forest.

"I fought with the Soviet partisans for a year and a half," Arad proudly says, "and I participated in the demolition of 16 German trains and rail tracks. We joined up later with the Red Army and I continued to fight with the Soviets until the end of April 1945. Immediately after the war, I threw off my uniform and immigrated to Israel."

Arad joined the Palmach, fought in the battles for Jerusalem, and subsequently served in the IDF as an officer in the Armored Corps and then as chief education officer. After leaving the army, he served until 1993 as chairman of Yad Vashem, and then went on to conduct extensive research into the Holocaust of Soviet Jewry and publish numerous books on the subject.

He moved into the retirement home some eight years ago and decided there, too, to continue dedicating his time to the subject that has accompanied him throughout his life.

"Some people etch landscapes, others etch stories," Arad says, "and I devote my work to the memory of the Holocaust and the memory of my family members who perished. It adds interest to my life. I'm 88 now and I became a widower a week ago. Now I will also have to etch my wife, Michal."