A beginner’s guide to Israel’s elections

How does the election system work, who is allowed to vote, and how is the next prime minister chosen: Everything you wanted to know about the Israeli electoral system but were afraid to ask.

Between the spins, the political mergers, and the many candidates vying for a spot in the next Knesset – Israel’s legislature – it’s easy to get lost in the details.

The Israeli electoral system is far from simple or intuitive; its structure will dictate how the elections will play out and shape the identity of the next government.

To guide you through the political forest that is the 2015 March election, Ynet has put together a simple – but thorough – explainer.

Electoral system

Unlike the US, Israelis vote for parties but do not directly determine which politician will head the next government. Instead, voters cast a ballot for one party, and the faction with the most votes gets a chance to form the next ruling coalitions.

Essentially, the elections for the government are actually a vote for who will sit in the 20th Knesset – a 120-person body of MKs.

The Israeli system differs in one other central way – the entire country functions as a single district. Unlike the British parliament, on which Israel's founding fathers modeled the nascant state's legislature, all 120 seats in the Knesset are elected through a national process – much like a US senator must campaign across his state.

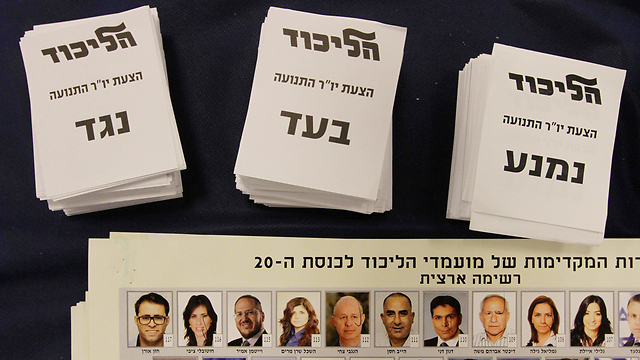

Party lists

Each party puts forward a list of candidates, and the number of seats that each party receives in the Knesset is proportional to the number of votes received: A party that won 15 percent of the general vote will hold 15 percent of the seats in the Knesset seats.

The candidates of any given list are elected to the Knesset based on the order in which they appear – the higher up the list, the greater the candidate's chance of recieving a Knesset seat.

The result is a multi-party system considered to be highly representative – as each citizen has a wide array of parties to choose from, some with only nuanced ideological differences between them. However, this tends to result in highly unstable governments comprising a large number of relatively small parties.

Surplus votes

The excess votes for each party – ballots which do not translate into a whole Knesset seat – are "donated" by smaller parties to their larger allies as part of what is called a "surplus-vote agreement."

For example, in the last elections, all excess votes for Bayit Yehudi were given to the Likud and a similar deal between the two will exist during the upcoming election as well. This method is known around the world as the Hagenbach-Bischoff method (in Israel the Bader-Ofer method) and is an attempt to strengthen political blocs at the expense of smaller parties.

Thus, when a voter casts his ballot, it is important for him to be aware of the surplus deal the party has signed – as their vote might end up contributing to a different party's success.

At times, surplus deals can lead to conflicting political arrangements.

For example, during the last election, the left-wing Labor signed such a deal with the centrist Yesh Atid in the hopes of strengthening what they thought would be a center-left coalition. However, Yesh Atid's surplus votes ended up helping Netanyahu form his coalition without Labor after the prime minister reached a deal with Yesh Atid chairman Lapid – thus leaving Labor in the opposition.

Election threshold

The minimum number of Knesset seats a party can hold is 4 seats – or 3.25 percent of the general vote. The threshold was put in place to prevent one or two-person parties and to encourage people to vote for larger parties or blocs. In previous elections, the threshold was 2 Knesset seats.

A direct result of this new threshold is the Joint Arab list – a unified bloc of the three Israeli Arab political parties – each of which had averaged 3-4 Knesset seats in past elections and were thus on the cut-off point. To prevent a massive loss in Arab political representation, the three parties banded together.

Although the move forced all three to swallow their political differences, it is expected to enhance their relative power.

Ironically, the new threshold might backfire on its sponsor: Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, whose Yisrael Beytenu spearheaded the Governance Law that saw the threshold rise to four seats is now polling at five seats, a massive decline since their heyday as a party of influence.

The left-wing Meretz – a fixture in Israeli politics – is also hovering around the five-seat mark after the results of the Labor primaries stole their thunder.

Yachad-HaAm Itanu – a Shas offshoot party led by its former chairman Eli Yishai – is currently polling at only four seats, a close call considering the poll’s margin of error.

Who forms next government?

After the votes are tallied and the Knesset seats are distributed – the political game of coalition-forming begins.

Putting together a ruling coalition in Israel is a delicate game of numbers and political wheeling-and-dealing between parties, who must cobble together a majority of 61 Knesset to form the government.

The heads of the different parties are invited to meet the president and each recommends one person to form the next government. The person with the most recommendations – or the best odds of gaining a majority in the Knesset – is given a mandate by the president to negotiate with the different parties to form a coalition. If they succeed, they become the next prime minister.

Race to 61

The politician hoping to sit at the helm of the new government has 40 days to negotiate with the different parties to join his or her coalition – in return for their support, parties are offered ministerial positions, policy decisions and even a veto right. However, one party’s demands can often cross another potential partner’s red line.

For example, when the last government was negotiated, religious Zionist leader Naftali Bennett secured the right to vote outside coalition lines in all issues relating to religion and state, thus clearing the way for the Yesh Atid – a secular party – to join the coalition and promote its own agenda.

Should the allotted 40 days pass without a majority reached, the president repeats the process – sometimes extending the mandate to the same person or giving it to someone else. If 100 days pass without a coalition being formed, new elections are called and the entire process begins anew.

For example, in the 2009 election, Tzipi Livni’s Hatnua gained the most votes and was thus selected to lead the coalition building process. However, after two attempts, Livni failed to reach the needed majority after negotiations with Shas went sour.

The responsibility to form the government then fell on Netanyahu, though the Likud had won 27 Knesset seats as opposed to Livni’s 28.

Who can run and who can vote

Parties, lists, and political blocs can run together.

For example, the "Zionist Camp" is running on a joint ticket though it is comprised of left-wing Labor and centrist Hatnua. The parties can chose to remain together after the election – as was the case when Likud merged with Yisrael Beytenu during the current government – or disband into different factions – as the United Arab list is expected to do after the vote.

Any citizen over the age of 18 can vote and participate in the elections, including those with criminal records. However, the voting itself takes place only in Israel, preventing expats and world Jewry from participating.

Diplomats, soldiers and sailors are the exception to this rule and are allowed to vote with absentee ballots.

Although rare, some parties are barred from running. The party lists are confirmed by the Israeli Central Elections Committee, comprised of MKs and a Supreme Court judge. The committee has banned four parties from running in Israel’s history; though all but one ban has been rescinded.

According to the state, a list which acts directly or indirectly against the existence of the State of Israel as the state of the Jewish people or against its democratic nature; a list which incites racism; a list which supports the armed struggle of an enemy state or a terrorist organization against the State of Israel cannot participate in the elections.