Grading Netanyahu's economic policies

Analysis: A look at how the prime minister's economic policies have measured up in the past six years since he took office for the second time in 2009.

Regardless of the second Netanyahu government's economic policy, the Israeli market managed to quickly pull out of the global crisis and after negative growth was registered in the last quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009, the market went back to positive growth in the second quarter of 2009.

At the end of Netanyahu's second government's first year, the Israeli market grew by 1.9 percent. Growth is always measured in a relative manner, so the low starting point led to a relatively high growth of 5.8 percent in 2010, the first year after the economic crisis.

However, in 2011, the market's positive growth rate was on the decline at 4.2 percent, which continued into 2012, with a 3 percent positive growth rate.

The average annual growth rate in the four years of the second Netanyahu government was unable to measure up to the growth rate noted in the previous four years (5.2 percent) and stood at 3.7 percent.

The growth rate from 2012 was more or less maintained over the first two years of the third Netanyahu government. A growth of 7.2 percent was registered in the last quarter of 2014, but this is not surprising considering it followed Operation Protective Edge in the preceding quarter, in which the growth rate only stood at 0.6 percent.

Public health system weakening

The health system has been in turmoil since 2009. On the one hand, funds arrived to increase the number of beds in hospitals and for the mental health reform that had been in a stalemate. On the other hand, when the bigger picture is examined, the health system's shortage is estimated at billions of shekels, with only the HMOs reaching a deficit of over NIS 2 billion in 2014, while government hospitals reached a deficit of some NIS 1 billion.

The relatively low level of investment in the public health system led to packed emergency rooms, reaching 200 percent capacity and higher in some of the hospitals, where those who came to seek treatment this winter found hallways filled with beds and overcrowded dining rooms.

This lack of investment in the public health system directly impacts the public's expenses on health. Since 2009, the rate of private funding in the total national health expenditure rose steadily from 37.7 percent to 39.7 percent, which caused an increase in expenses totaling NIS 1.5 billion a year. This money comes out of the public's pockets in various forms of health insurance - including policyholder's participation in funding of medicine and private operations. The public had no choice but to add personal funding, because the public health system did not provide it with sufficient resources.

Cost of living: Protests and commissions didn't help

Over Netanyahu's two latest governments, from 2009 until January 2015, food costs climbed 12 percent - including the cost of fruit and vegetables. It's important to note, however, that some of these increases can be ascribed to the global increase in prices of raw material.

Following the mass protests sparked by the increase in the price of living that took place in the summer of 2011, the government tried to fight the increasing food prices by forming the Kedmi Committee to investigate ways of ramping up competition in the field. The chapter in the recommendation that dealt with supplier-retailer relations went into effect in January 2015, but is not expected to lead to a significant change.

In general, the committee's conclusions are far from the expectations of citizens. For example, the committee recommended decreasing taxes on food imports, but the move will mostly apply to products not manufactured in Israel - not creating more competition in the local market. The government also chose not to adopt some of the conclusions in the committee's report, such as the recommendation to force manufacturers to reexamine the pricing of products sold to retailers.

In 2014, there was a drop in food prices that can be attributed to the fierce competition between the different chain stores in Israel. And yet, according to market estimates, food prices are actually expected to rise in coming months ahead of the May implementation of a chapter in the Kedmi Committee's recommendations which requires transparency in pricing.

Housing: An abundance of plans without results

At the beginning of his term as the construction and housing minister in 2009, then-minister Ariel Atias of the Shas party announced that housing prices would drop within a year. But in reality, prices have continued rising steadily and over the past six years, the price of an average apartment rose by 41 percent.

Atias focused on the effort to increase marketing of apartments alongside increasing the amount of housing units built as part of the Price for New Residents ("Mechir LaMishtaken") program. However, at the time, Ariel got a cold shoulder from then-finance minister Yuval Steinitz.

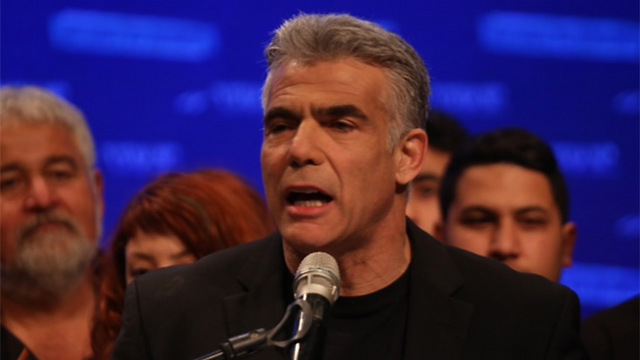

The new government formed in early 2013 brought Yesh Atid ChairmanYair Lapid into the Finance Ministry. Lapid was determined to solve the housing crisis and even formed the "housing cabinet," which he personally led. During Lapid's time in office, the Mechir LaMishtaken program was abandoned and new programs were adopted instead. These plans included Room for Rent ("Dira Lehaskir") - a plan to build more apartments for rental, Target Price ("Mechir Matara") - a plan to lease lands to contractors who would in turn commit to a price lower than 20 percent of the area's average, a plan for umbrella agreements with municipalities, and a plan that sought to give the treasury a budget to develop infrastructure in new neighborhoods. The crowning glory, however, was Lapid's 0% VAT plan which aimed to give first time home buyers an exemption from paying VAT, if the purchase was made through a contractor.

The main problem with Lapid's plans was that each program was supposed to complement the other and since most of the term was spent on formulating the plans, most of them never got to be put into practice.

Lapid's 0% VAT plan was pushed back due to political arguments until it was finally scrapped by Netanyahu; the Target Price ("Mechir Matara") program has only been underway for a month; and the Room for Rent ("Dira Lehaskir") program has yet to be implemented.

The mortgage market did not wait for plans and slogans either, and the loans that banks granted for housing reached NIS 283 billion by the end of 2014 - an 86 percent increase from the end of 2008. The average mortgage also became more expensive and currently stands at over NIS 600,000, with the price of an average apartment increasing by 41 percent.

The sharp increase in activity made the banks more dependent than ever on the real estate market and over the past year, the Supervisor of Banks announced that mortgages were a big risk to the stability of the banking system. Even in 2014 alone, the year in which Lapid announced his grandiose plans and called on young people to wait with their plans to buy an apartment, ended with the same amount of mortgages registered in 2013.

Security: No trace of streamlining

The tension between the defense system's monetary shortages and the financial burden it imposes on taxpayers has created difficulties for the state budget and the army's activity for many years. When Netanyahu was the finance minister, it was clear to him that the defense budget was not the only budget to be focused on and when other budgets are ignored it causes financial and social consequences for the public. Meanwhile, in his current term, Netanyahu as prime minister had already begun to see additional interests at play when it came to the defense budget.

If reducing security expenses was as important to Netanyahu as he has been saying when he was finance minister, he would have demanded the defense system to streamline, which he did not do. In reality, the decisions made under his leadership made no economic sense.

For example, the NIS 4.3 billion added to the 2015 defense budget and the NIS 8.5 billion added to the 2014 budget were Netanyahu's way of appeasing his main Likud ally, Defense Minister Moshe Ya'alon, and weakening former finance minister Yair Lapid, Netanyahu's rival from Yesh Atid.

If Netanyahu truly wanted to take care of Israel's security, he would have had to a make some difficult decisions: Extending the defense budget on the expense of social budgets or making significant changes in the defense system's structure.

Netanyahu did initiate the formation of the Locker Committee, entrusted with determining the defense budget, but that happened only in 2014, after six years of political struggles between the different ministries which resulted in Netanyahu deciding the budget allocated to each ministry.

Sources in the government, however, say the Locker Committee is not expected to make fundamental decisions, which is why it will fail to solve the problem.

The recommendations of the Brodet Committee, which tried to determine the defense budget for 2008-2017 and demanded NIS 30 billion worth of streamlining with an addition of NIS 46 billion to the defense budget, were not implemented.

The defense ministry claimed it did not receive the additional budgets, but on the other hand they did not keep up their end of the bargain of streamlining NIS 30 billion. Furthermore, the government did not enforce their decision to streamline the defense system's spending.

Success in employment, failure in welfare

According to experts, the welfare issue should have been revitalized during Benjamin Netanyahu's premiership. The Gini index, which measures income gaps in the market, went down 6.6 percent over the years 2009-2013. According to the Finance Ministry, this is a result, among other things, of introducing families into the job market that until 2003, when Netanyahu was finance minister, were relying on National Security stipends which were dramatically cut in 2003.

Whether this was the reason for the narrowing of the gap or not, the welfare system in Israel still does not look great due to overcrowding in welfare offices and the ever-increasing reliance on NGOs and philanthropists to continue keeping the poor afloat.

Even if the prime minister cannot be directly blamed for all of these issues, there is one issue he should definitely be required to address - the financial crisis that the National Insurance Institute could find itself in.

Two reports published over the past two years clearly and unequivocally stated that by 2038, the National Insurance Institute will not have enough money to pay stipends. Since the release of these reports, nothing has been done and the future of the most important social institute in Israel is still shrouded in fog.

The rate of unemployment in the market and the rate of participation in the workforce have both seen an improvement since 2009. From almost 10 percent unemployment rate in the middle of 2009 when Netanyahu first returned to the Prime Minister's office, to 5.6 percent in the last quarter of 2014.

The problem is that this improvement comes at the expense of something else - wages. In the industry, the average wage has been on the rise since 2011 until the end of the third quarter of 2014 (the latest data available) by some 2.8 percent. Meaning, now that the market has started recovering from the global economic crisis, the increase is some 0.7 percent a year over the increase in the consumer price index.

It is also important to note that as it is, half of Israeli citizens make no more than NIS 5,493 a month, and many in the public feel their ability to make ends meet has not significantly changed in recent years.

Likewise, it is also important to note that at least part of the explanation for the gaps in wages lies in global circumstances. The freeze in the average wage is a problem almost all Western markets have experienced. Except that in Israel, the solution was always to increase human assets as much as possible in order to increase competition and efficacy in the Israeli market.

Despite Israel's identity as a startup and cyber nation, there is a gap compared to Western countries in terms of employee productivity - how much work is accomplished in an hour - which directly depends on the worker's education and skills. In this arena, Israel is lagging behind.

Several studies by The Bank of Israel show that one of the reasons for the gap in income between the Israeli employee and his European counterpart is in the education each possesses. This parameter has not seen improvement since 2009.

Amnon Atad, Mickey Peled, Tomer Varon and Dotan Levi contributed to this report.