Historical Haggadahs show centuries of longing for Zion

Dr. Yoel Finkelman, curator of the Haggadah collection at the National Library in Jerusalem, says longing for Zion is an extension of central Jewish theme of redemption.

Jews in exile – be it in Russia or Yemen – dreamed of redemption, and of the Land of Israel. And over the years, the Passover Haggadah – with its narratives of nationalism, salvation, slavery and freedom – was tailored to fit the Jews of each country, according to their dreams.

Thus, the Haggadah we read at Seder has many added, engaging sections, showing a variety of postcards of Jewish history - and the history of Zionism that emerged in the last century.

Tens of thousands of Haggadahs - the world's largest collection – is housed at the National Library in Jerusalem. In one, appears the dream of modern Zionism: A Jerusalem of stone houses and plowed fields - "the new Jews".

"From our view, it is clear that this Haggadah is full of nostalgia for the Second Aliyah, and the ethos of manual labor," explains Dr. Yoel Finkelman, curator of the collection at the National Library.

"The traditional Haggadah has become part of the Israeli-civic religion. At that time, in the 1930s, many did not celebrate a Seder with underlying religious beliefs, but as a part of a ceremonial-civic celebration, celebrating the fulfillment of the Zionist dream in our country. "

Surprisingly, he says, the story of redemption and the Land of Israel is almost completely missing from the classic Haggadah text, "except for small references such as 'next year in Jerusalem', a line that does not exist in every version."

Jerusalem of the imagination

According Finkelman, the text of the "narrator" - most of the Haggadah – crystallized between the 7th and 11th centuries. He emphasizes the Exodus from Egypt, and its importance; this is the central story of the traditional Haggadah.

"On the other hand, Jews are so imbued with the overall context of the Exodus, naturally they cannot fail to extend the story of 'peace and tranquility' to the Land of Israel," he says.

"There is almost no part of Judaism that does not mention the hope of redemption and salvation. And certainly it is called for as direct continuation of the story of the Exodus.

"Even in times of security and calm feeling of 'exile' never left," he says. "Even the Jews of Yemen or Amsterdam, in the 15th century or 18th century, felt 'Egypt' wherever they lived, when their dream – their vision - was of Jerusalem of their imaginations."

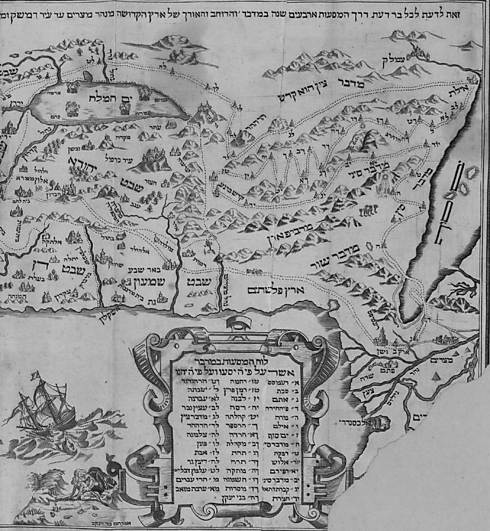

One Haggadah he brings out to prove his claims is the "Amsterdam Haggadah," written and illustrated in 1695. At the end is a map of the Land of Israel "in ancient times" - a clear connection between wandering and salvation, describing the journey to the "Promised Land".

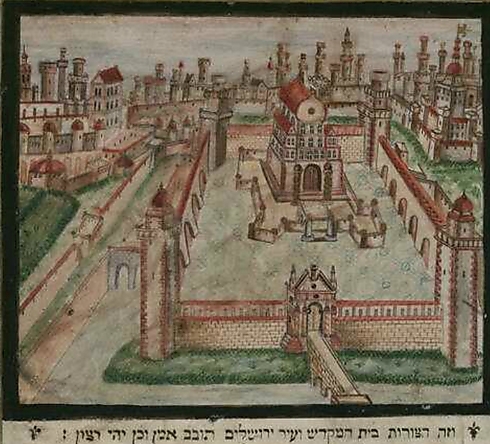

Finkelman pulls out an Ashkenaz Haggadah, also from 18th century, complete with hand-drawn illustrations and that not only places the phrase "the heart of Jerusalem Hallelujah" at the top center, but also adds a figure of King David in the Temple, as cherubs hover in the background.

Renaissance Jerusalem

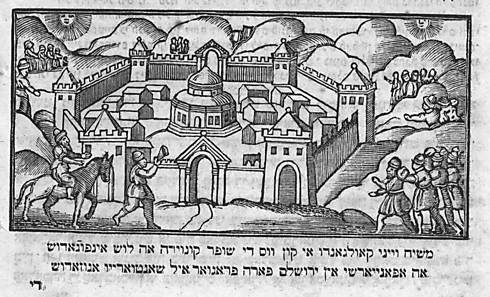

The Varna Haggadah of 1803, written in Yiddish and Hebrew - shows the Jerusalem as a Renaissance city, with the Messiah blowing a shofar at its gates, dressed in period clothes.

The German Haggadah from the 18th century is also illustrated in the same way, and the caption reads: "And this is form of the Temple and Jerusalem soon to be built, Amen."

According to Finkelman, this is a prominent theme, which continues the classic line of what is known as "scrolls of the holy places" - a kind of guide book written for Christian pilgrims on their trips to the Holy Land, from the Renaissance onwards.

The Zion connection

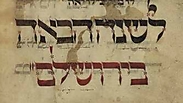

The few Haggadah verses that mention Jerusalem - for example, "Next year in Jerusalem" – were decorated and enlarged to emphasize their importance. This is clearly seen in the Rothschild Haggadah of 1450, one of the most beautiful and most decorated in the collection.

He argues that the liturgical longing for Jerusalem is not part of the classic Haggadah, and was introduced into many communities in order to address the deficiency in the text.

Finkelman says many Haggadot have additional texts in which the Land of Israel is the focus.

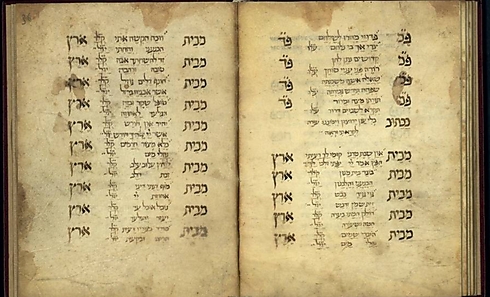

He cites the Wolf Haggadah, one of the earliest in the collection and dating to 14th century Provence, which adds text to every mention of life in exile, and text on the Land of Israel.

In other words, he says, there was a deliberate attempt over time and across the world, to strengthen or express the connection to the Promised Land.