Ukrainian Jews waiting for Israeli recognition

Thousands of Jewish refugees gather in Jewish Agency's 'fugitive camps' after fleeing Ukraine's battle zones. But on their way to a better future in Israel, they have to prove to the state – and mainly to the Rabbinate – that they are halachically Jewish.

An average of 10 people die every day in Europe's backyard in the battles taking place in the fighting zones. Jews who have managed to flee the battle zones gather at a Jewish Agency refugee camp (or "fugitive camps," as they are called euphemistically) as a transit stop, on their way to a better future in Israel.

But the bad (and known) news is that not all those who have succeeded in proving their eligibility to immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return to the Israeli consul will also be able to live in Israel as equals among equals. Most immigrants are required to prove their Jewishness to the Chief Rabbinate as a condition for getting married in Israel. And that's, it turns out, is a much more complicated matter.

According to official estimates, tens of thousands of Jews still live in Ukraine, but no one has accurate numbers. The Jewish community leaders say many of these people don't even know that they are Jewish, and even those who claim to be Jewish may not be able to prove it to the Israeli authorities, not to mention the Chief Rabbinate.

Last chance to prove one's Jewishness

The immigration rate from Ukraine to Israel has grown by hundreds of percentage points, reaching a monthly average of more than 1,000 immigrants since the beginning of 2015, in what appears to be the biggest wave of aliyah since 2003.

Jewish Agency officials refer to those who reach them as "fugitives," since Ukraine is intentionally avoiding granting basic refugee rights to its citizens who have lost everything they had.

Between procedures and bureaucracy, members of the Shorashim organization are now trying, in a last-minute effort, to not only prove these Jews' eligibility to make aliyah under the Law of Return, but also the halachic Jewishness of as many of them as possible. For this reason, Shorashim inaugurated about two weeks ago an office in the Jewish community's Menorah Center in Dnepropetrovsk, which will also serve the refugees from the Russian-occupied areas.

Two people have taken it upon themselves to stop the catastrophe which has already become a national problem in Israel, with hundreds of thousands of people whose Jewishness is not recognized by the Rabbinate: Dr. Yaacov (Yasha) Gaissinovitch, a successful local mohel, the man who can get hold of any piece of information, often in ways he cannot elaborate on; and his partner in the crazy journey between elderly women in villages and moldy archives – Gene Blotsky, a local Jewish lawyer.

The organization members understand that it's almost the last chance to prove a person's Jewishness – a pretty complicated matter which requires an Yiddish-speaking grandmother, rare documents from pre-World War II archives, and sometimes also DNA tests. The journey to one's roots is a desperate journey against time, before it's too late, as the older generation which still knows something about its origin is fading.

This complicated operation is funded by the Triguboff Institute through a fund established by Australian billionaire Harry Oscar Triguboff, who is originally from the Soviet Union and is involved in variety of infrastructure projects in Israel.

'Operation Grandma'

As many as 800 people have already passed through one of the "fugitive camps" on the banks of the Dnieper River since the beginning of the battles, on their way to the Holy Land. The small children I meet there hope to start the next school year in Israel, with the help of God (and the consul).

Maxim Luria of the Jewish Agency introduces me to Anna, a single parent who fled Donetsk, a moment before everything went up in flames. She has been here since then, waiting with the others for the anticipated approval to immigrate to Israel.

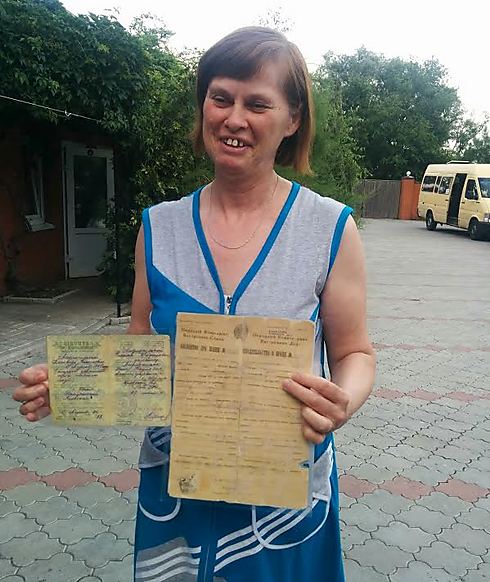

Anna Neumann, Hannah in Hebrew, is lucky. The Shorashim members are relieved when she carefully pulls out a yellowish original document from 1926, the days of the beginning of the Soviet revolution. The document states the origin of the family of Anna's maternal grandmother, Hannah, when she got married. Her father's name, according to the document, was Nahum and her mother's name was Sara. Her place of birth and residence was Shpoli, a well known Jewish town recognized by anyone who was raised on the "shtetl" stories.

Rabbi David Stav, chairman of the Tzohar organization, who is visiting the camp with us, holds onto the document excitedly: "This is the unequivocal evidence the Shorashim representatives are fervently looking for," he says.

"There are roots on the mother's side that are important for Jewish Halacha, which determines a person's Jewishness according to the mother," Attorney Blotsky explains. Rabbi Stav concurs: "We went back four generations here on the maternal side, and this document will determine her Jewishness. It's important because she is immigrating to Israel with her son, and he will want to get married at some point. This is her chance to prove his halachic Jewishness unequivocally."

Our war and their war

The Pak family is also waiting for an approval to immigrate to Israel. They have no documents from the early Soviet revolution to prove that they are Jewish. It's a bit more complicated. They are from Donetsk. They have been joined by their cousin and little boy from the Crimea peninsula, which has already been fully occupied by the Russians. The grandparents with the relevant documents have not been permitted to leave Donetsk, and the family members are now waiting to reunite with them at the camp.

Yuri Pak decided that he wanted to make aliyah a year ago. The family even visited Israel last summer during Operation Protective Edge. His wife, Viktoria, hesitated. "But when we were there in the summer, it strengthened my feeling that that's where we want to live," she says.

"I saw the importance given in Israel to every fallen soldier. Here (in Ukraine) they just write, 'Three people have been killed.' Without a name, without a story. It was important for me to see that the state gives a lot of meaning to the individual."

The Paks don’t like to talk about what they left behind. Tears appear in the corner of their eyes when I ask them about it gently. They tell me what they found the day they returned from Israel: Three missiles had directly hit their neighbors' home, leaving complete destruction. Without unpacking, the family members fled.

When I ask their 14-year-old daughter, Alika, who hopes to start high school in Israel, what are her favorite things in Israel, she thinks for a while and then replies: "Patriotism, unity, army, culture and the fact that every person can study what he wants and find his place. That's what I like about Israel."

Rabbi must also prove he is Jewish

The Pak family was famous among the Jewish community in Donetsk before the Putin era. They were very involved in the communal activity, including studies in the Jewish school. But the distance from here to the Chief Rabbinate's seal of approval appears to be very far.

"Even if the identity card says the mother is Jewish, it's not enough," a Jewish Agency representative says sadly. "They ask for all kinds of other documents, older ones. They are afraid of fraud."

Shalom Norman, CEO of the Triguboff Institute, who immigrated from such a camp himself in 1956, stresses that "documents with the word 'Jew' from before 1941 can prove a person's Jewishness beyond any doubt, as being Jewish wasn't such a bargain at the time."

The burden of proving their Jewishness doesn’t only fall on the shoulders of Jews who did not lead a religious life or did not belong to the Jewish community. Chabad emissary in Dnepropetrovsk, Rabbi Shmuel Kaminezki, says he faces a problem too: "It will be difficult for me to prove that I'm Jewish. My grandparents fled at the end of the war, and there are no documents. I wanted my daughter to participate in the Masa program and get to know Israel. The consulate people said to me, 'That's very nice, but you must prove that you are really Jewish."

Yasha will find the proof

So how do you prove a person's Jewishness? You go through the archives, starting with the Soviet army's archive to the Red Cross archive, which Norman says includes documentation of about two million Jews who fled during World War II following Joseph Stalin's "scorched earth" policy.

"Most of the Jews who live in Ukraine today, or immigrated to Israel from Ukraine, are the offspring of 'the great evacuation,' and you can find documentation of that in the archives, if you know where and how to look of course.

"Yasha (Dr. Gaissinovitch) always goes in through the window, and if there is no window – then through the chimney. He succeeds in obtaining things fast, after everyone else has given up: He locates grandmothers, tombstones, documents. I always say that the Jews here trust him with their most precious thing," he adds jokingly, referring to Dr. Gaissinovitch's profession as a circumciser.

Shorashim CEO Uri Shechter notes that "every case of proving a person's Jewishness which has been submitted to the Chief Rabbinate's approval has been approved. This points to the power of the work being done here."

Michael Katats, a young Jew whose parents escaped to Kiev to get away from the war, also wants to immigrate to the Jewish state. Part of his family is already in Israel, and fortunately for him, he is Jewish from his maternal side. His relatives who have already made aliyah sent a picture of great grandfather Shmuel and grandmother Chaya in traditional Jewish clothing, along with other documents revealing clear Jewish names, including combat documents from World War II which state that the document's owner is Jewish.

"This is the most important document for proving one's Jewishness," he says proudly, after experiencing firsthand the burden of proof. His grandparents were rescued during the Holocaust by a Ukrainian woman who hid them in her house until the end of the war and was later declared a Righteous among the Nations.

"Despite all that, I had to visit the embassy at least five times," he says. "Each time they said to me, 'We need another document now.'"

Now, after the consul approved his immigration, the Shorashim representatives will have to make sure that the grandson of Shmuel and Chaya, who miraculously survived the Holocaust and Soviet cleansing, will not be rejected by the Rabbinate in the future.

Are the Jews stopping Putin?

The Chabad organization in Dnieper, which runs the local Jewish community fearlessly, is happy to help the immigrants. "It's also a matter of saving lives," Rabbi Kaminezki explains. "The medical care here is horrible. People die at an early age, simply because healthcare is lagging behind. By convincing them to make aliyah, you are giving them a gift of 50 years of life.

"With every Jew that makes aliyah, I find two new ones. Just now, as I flew here from London, I spoke to a local couple who told me, 'We are not Jews, but the grandmother was Jewish.' Clearly, they are entitled to make aliyah, and in this case they are also halachically Jewish.

"If it were not for the Jewish, Putin would already be here, in Dnepropetrovsk, too," rabbi Kaminezki believes. "They had a detailed occupation plan, but the money managed to unite the city, from the police to the mafia."

He says even the ordinary Ukrainian sees the Jewish Ukrainian oligarchs as local heroes who saved Dnepropetrovsk from Putin.

One of the local community leaders, speaking anonymously, says to me: "At the end of the day, this isn't an ideological aliyah. We refer to it as the 'salami immigration.' People are looking for a good life in Israel. Being Jewish in Ukraine today is like being a rock star. It's an insurance policy which says that you don't only belong to the leading and influential elite – which is also perceived as smart and rich – but also that if things don’t work out for you, you can always get up and leave. To Israel, of course."