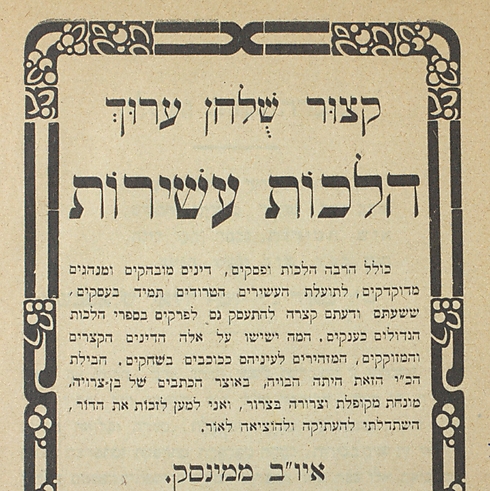

How do you say "tycoon" in Yiddish? An intriguing booklet called "rules of the rich" written in 1912 proves that this isn't such a strange question. The essay, a biting parody penned by writer Joseph Brill as a Torah-style "book of laws," reveals unflattering class differences in Eastern European Jewish society at the start of the last century.

Even in 1912 – some 100 years before the concept of "social revolution" came to be known in Israel – there were those who opposed the tycoons of their generation and mocked the rich Jews of the time whose only desire was to accumulate capital and wealth while ignoring the financial dire straits of their poorer brethren.

The booklet was printed on cheap, simple paper and sold for 30 kopecks. The document was recently added to the Israeli National Library after being located at a private auction abroad.

The booklet addresses topics such as "signs of purity and impurity in a wealthy man."

One cannot ignore that the booklet's cynical and contemptuous tone towards the rich Jews of the time – the "men about town" from Sholem Aleichem's books. It is also a sharp criticism of religion and the institution of halacha that pops up between the lines.

The conclusion of the booklet is that money, at the end of the day, buys everything – even the rabbinical establishment that is supposed to be concerned with protecting the simple individual from the greed of the rich.

"The booklet reveals a very clear tensions between the educated and the groups of observant rabbinates at the time," says Dr. Yoel Finkelman, the treasurer of the Judaism section in the collections wing at the National Library.

"It expresses the opposition of the younger generation to the rabbinical establishment, which is echoed in this booklet. And all this in a period in which socialist and Marxist ideologies sought to remake society and pull capitalists away from their control over wealth, for the good of the simple man in the street," Dr. Finkelman continued.

"Compared with today, the gaps were much wider," he added. "It's not like here where the middle class feels exploited, but real poverty. Poverty and hunger that the majority of us are spared from these days."

Grandfather was a rabbi, grandson a socialist

Finkelman notes that the booklet was printed at a unique time in history: "The booklet was printed in a period that saw profound changes among the Jewish family structure.

"It wasn't uncommon to see three generations in one family where the grandfather was an observant Jew that strictly adhered to the commandments; the parents were trying to mold themselves after Europeans; and the grandchild was a socialist or a Zionist in proper education.

"This is a period in which two-and-a-half million Jews in Eastern Europe and the US were killed – not due to ideology but because of real financial distress that gave people no choice but to up and leave," Dr. Finkelman said.