The legacy of the last Treblinka revolt survivor

Samuel Willenberg, considered the last Holocaust survivor of the Treblinka revolt, which led to the closing of the extermination camp, passed away at the age of 93 last month. His widow Ada, a survivor herself, explains why she's angry at the way survivors in Israel are being treated and talks of life with her optimistic husband, who never stopped dreaming and creating.

Samuel Willenberg passed away last month at the age of 93, after having survived the uprising that put an end to the activity of the camp where 900,000 Jews were exterminated. "It's very strange that a man who saw so much death and evilness, lost his two beloved sisters and survived the camp alone, had so much joy in him," his widow says amazed. "He liked to drink, and he loved to eat, and he loved to travel, and he loved women. Almost until his death, he had endless energy and a million crazy ideas."

And you?

"I was in his shadow a little bit. I just let him have the stage, because his story was more dramatic. I am a Holocaust survivor who escaped from the Warsaw ghetto, but Igo, as we called him, was among the few who survived Treblinka and escaped from it. We are completely different. I'm serious and he is adventurous. I am quiet he is self-centered. I try to forget the past and invest in the present, but Igo lived the Holocaust."

The only had one thing in common - choosing to tell all that had happened to them. They started telling their story when their only daughter, architect Orit Willenbrg-Giladi, was born, and kept telling it until recent years, when he started forgetting things and had to ask for her help. "Most of the survivors remain silent," she says. "People think that it's because of the pain and difficulty, but the real reason for that is the horrible attitude toward Holocaust survivors in Israel. When we told them what we went through, people asked us 'why didn't you resist? After all, the Germans were few and you were six million.' The children and youth were learning about the heroism of the Maccabees and of IDF soldiers in Israel’s wars, while in the Holocaust millions went like sheep to the slaughter. There were so many stupid questions and insulting comments, that the survivors began to withdraw and kept quiet.”

And you?

"We were also offended. By what right does a person ask such questions? They weren't really there. They didn't stop to think that those millions were first in the ghetto, suffering from hunger and disease, and when they reached the camps, they were already half a person anyway. People asked Igo, 'what took you so long to organize a revolt at Treblinka?' It's hard to explain that in the camps, people were likely to snitch on each other when they suspected an organized uprising, because if someone managed to escape, the (Nazi) commanders would immediately murder 30 Jews in his place."

And yet, you didn't stop telling your story.

"Of course. Because we have to remind future generations. When reactions (to our stories) were harsh, I became reserved. I didn't get angry. But it drove Igo mad. Sometimes he would really insult people. Sometimes I had to hold him by force, so he would not hit people."

The whisper that saved his life

Like her handsome husband, Ada Willenberg is vibrant and dominant. At the age of 87, with her mobile phone, she remains connected to life with ageless zeal. "Why did you get 75 percent on the exam?" she asks her grandson. "It's probably because you're sad. Please drive carefully. I have enough troubles now."

Many comforters arrive at the big house in moshav Udim, talking in Polish about the notorious death camp that Willenberg managed to survive. Aside from him, 66 others survived the Treblinka camp, and with his death, the memory of the revolt is gone.

Six thousand people were sent to Treblinka on the same transport as Willenberg in 1942, after the liquidation of the ghetto in Opatów. A huge number of people were packed inside the freight car without food or air. Many of them died during the trip. When those that survived the journey arrived at Treblinka, the purpose of their trip was hidden from them in the same methods used at the Sobibor camp: a fake terminal was built on the platform, flanked by signs pointing to other platforms, to the ticket booth and even to a cafeteria. Upon their arrival, the sick, disabled and the elderly were sent to a shed labeled as a hospital, where they were shot in the back of the head and thrown into pits.

Men and women were cruelly separated, to the left and right. This was done while the passengers were made to run, were beaten and yelled at. Women with children were placed in a hut on the left side of the field, where they had to undress and have their hair shorn. They were made to run naked along a track, as SS men and Ukrainians with their dogs standing along the track mercilessly flogged them with whips, until their death in the gas chambers. Some of the Jews were kept alive to carry out maintenance work and sort out the clothes, jewelry and valuables that were hidden within the victims’ possessions. While at the fake train terminal, one of those Jews whispered into Willenberg's ear that he should say he is a builder, and thus saved his life.

Willenberg's parents remained in Poland. "His mother was an Orthodox Christian who converted to Judaism," Willenberg's his widow says. "She had a birth certificate written in Russian, and on the other side it said that she converted, so his father glued a forged document on that side. They were able to arrange false papers for their children as well, but the Poles informed on the children, and they were taken to the camps."

Willenberg was added to a team at the camp that was responsible for handling the belongings of the dead. "His little sister was three years old when the war broke out, and the oldest sister was 22 years old. When they were 9in the ghetto, his little sister had a beige coat, and when she grew up, his mother added pieces of cloth on the coat sleeves. Whenever she had to extend the coat, she added a patch in a different color. Igo found the coat among the victims' belongings next to his older sister's skirt. That's how he knew they arrived in Treblinka and perished in the gas chambers."

On August 2, 1943, the great revolt broke out. "It was a hot day, and most of the camp's staff were bathing in the nearby Bug River," says Ada Willenberg. “The prisoners set fire to many buildings in the camp and during their escape they also set fire to the gas chambers and the weapons depot, which exploded. Because the sound of gunfire, SS units arrived and started chasing them. Many were wounded and killed. Igo was also hit by a bullet, but despite the injury he kept running and was saved."

Some 200 prisoners managed to escape the burning Treblinka during that heroic operation, but most of them were later killed by gunfire from the guards and the local Poles. Those remaining in the camp were executed, but not before they were ordered to dismantle the buildings and fences so the atrocities that took place there could be concealed. The camp area was plowed, sown and planted with trees. A farm was established there and settled by Ukrainian farmers.

Ada Willenberg was ten years old when the war broke out. Her family was deported to the Warsaw ghetto, but at age 14 she decided to jump over the walls of the ghetto and run for her life. "I was an only child, so I did not have brothers and sisters to lose," she says with a bitter smile.

"My parents were killed, and a Polish family hid me and cared for me until the end of the war. While Poles informed on Igo’s sisters, I saved by Poles. So I can’t hate Polish people. The woman who saved me had a three-year-old boy, but she hid me and saved 18 other Jewish children. So when people ask me, 'how can you love Poles?' I say, 'my parents were not killed by Poles, and I am alive thanks to them.'"

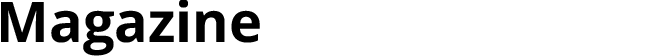

After Treblinka, Samuel Willenberg fled to Warsaw, where he joined the Polish resistance and took part in the Polish Warsaw uprising in 1944. After that he joined the ranks of the partisans. When the war ended, he continued serving as an officer in the Polish army until 1946, and it was during his service that he met the woman who would later become his wife. At the end of that year, he decided to leave Poland and move to Israel. "He left his parents and promised that when he is acclimatized in Israel, he will send tickets for them to also come," his widow said. "But on the way he received a Polish newspaper that stated that his father, the painter Professor Willenberg, was very sick. Igo immediately returned to Poland, but he didn't manage to see his father before he passed."

How did you meet?

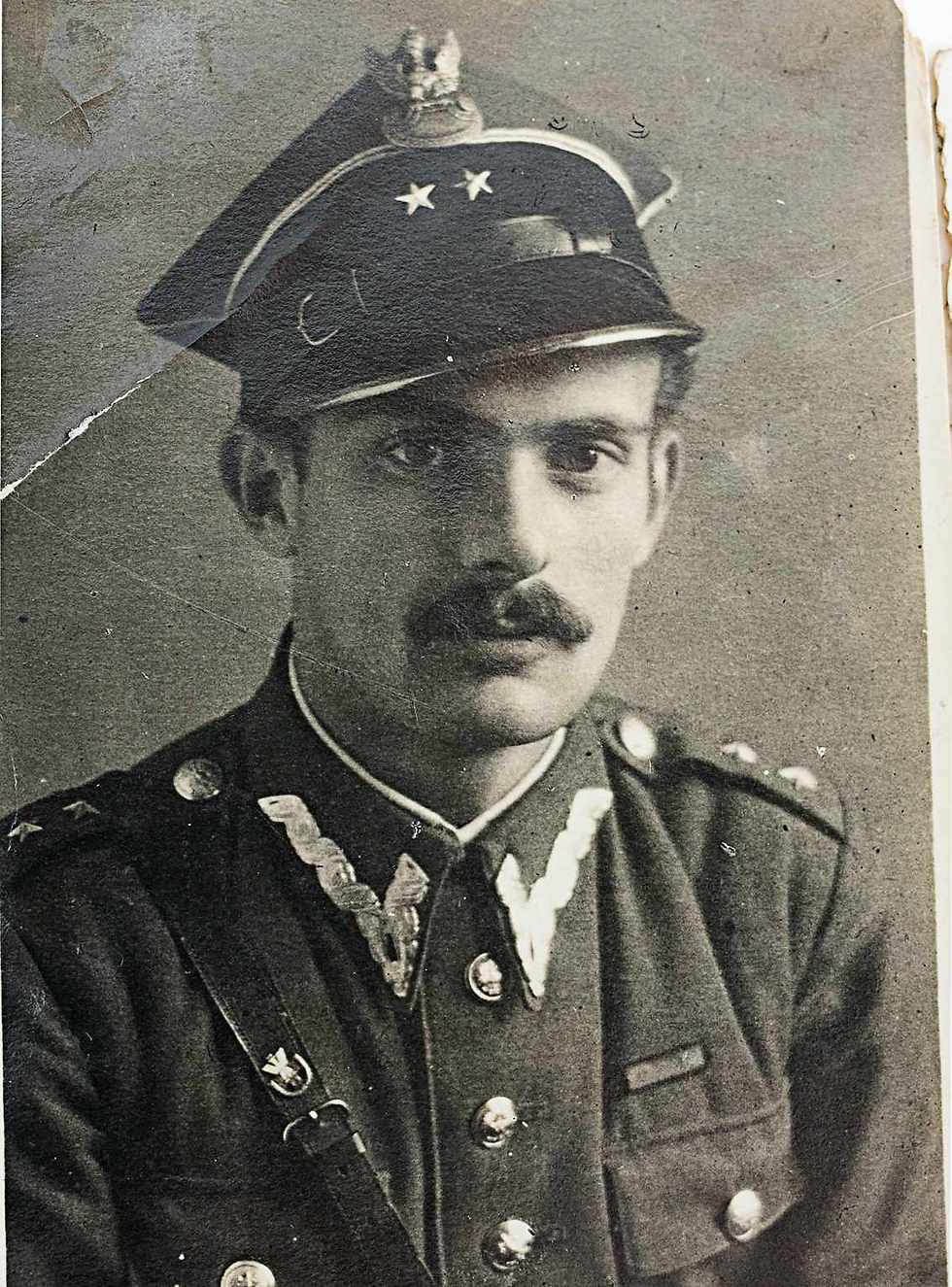

"I returned to Lodz and one day I was at a friend's house where I met a handsome officer, like a film actor. I asked him about a vacant apartment, and the officer said, 'I have a small two-room apartment. I'll rent it out to you on the condition that you marry me.' He was joking. Igo always said that a skinny little girl came to him wearing a black beret that was hiding half of her face. We met again before traveling to Israel. He was so happy to leave Poland. I told him, 'write me from your trip.' He said, 'sure, sure,' but didn't even ask for my address. Only later, when he returned to Poland following the death of his father, did we begin to go out with each other. We dated for two years and I could not decide if I should marry him."

Why?

"Because after the war there were not many women left, and every guy I met wanted to get married and start a family. I wanted that too, but I was looking for a man who would be like a father to me, and Igo was not the paternal type. He was an adventurer, and he had a mother who lost her husband and her two daughters. I was afraid she would not be willing to share with me the only thing that she had left. In retrospect, it was the opposite. Igo's mother also became my mother. Whenever there was an argument at home, the two of us were against him."

Somewhere to run

In 1950, the Willenbergs, along with Igo’s mother, immigrated to Israel and rented a small apartment in Tel Aviv. Ada was working in film production, and Shmuel in the Ministry of Housing.

"He was not happy in the city and wanted to live in the countryside," she says. "He had a fear of places that are impossible to escape from and searched for a house near the fields, so that if another Holocaust happens, there will be somewhere to escape the bombings and somewhere to pick edible plants. When he started earning a tidy sum, and we started looking for a house to buy, I found a nice apartment in the Bavli neighborhood, but Igo said, 'if you buy a house in the city, I will get a heart attack.' I gave in and bought a farm house in moshav Udim."

In 1960, their only child was born. Her name was composed of letters of family members that perished. "Igo's mother, who lost her two daughters and her husband, was depressed most of the time," says Ada. "But when Orit was born, she really came back to life. She looked after the baby when we were at work and always told me proudly that people keep stopping her on the street and asking about the baby’s beautiful blue eyes, which she inherited from her father."

What kind of a husband was he?

"His character was very complex, very impulsive, but also optimistic. We were very happy together and a bit frivolous. We loved to travel. We did not have furniture yet, we barely had beds, and I told my husband, 'maybe instead of getting tables and chairs, we could go abroad?' We took his mother, who suffered from heart disease, and Orit who was seven years old, and we went to Turkey and Greece and then went to Europe. Igo really liked to spend money, while I was more frugal, but we both liked to live. We wanted to make up what we lost. When they did a film about him for his birthday, people were interviewed for it who said he loved women and women loved him. But Igo spoke about me a lot and said what I always knew, that he really loved me. He was unpredictable, I never knew what to expect, and it was a big plus. I never was bored."

The Holocaust was prevalent in the household long before Samuel began the memorialization work that made him one of the world's best known survivors. "Our memories were similar, and when we got back to the past, it was with someone who was there and understood what we went through. We talked a lot about the Holocaust and wept over the beautiful childhood that we had and was cut off. When I would sing a song from before the war, he would immediately join in because he knew it. Igo had nightmares, sometimes he would wake up from dreams that returned him to Treblinka. He constantly mentioned his sisters and even in his final moments, he wept for them. And when his mother died in 1973, he constantly called out to her in his dreams. Igo was living in the past. I tried to erase it."

And were you able to do this?

"I have a selective memory. I remember the good things. So it was easier for me. Even though I was left alone at a young age, unlike Igo, I always had good people around me who helped me. In the camps, Igo encountered pure evil. There he lost God. Since he came to Israel, he would not hear about God. I talked to him a lot about that same God that kept him alive, out of all of those who came to Treblinka, and about the happy life that we had after the war. But Igo always said, 'I'm not willing to have a dialogue with him.'"

Was your daughter also part of the conversations about the Holocaust?

"Of course. When they came from Swedish television to interview her about how the Holocaust affects the second generation, Orit said to them, 'You picked the wrong subject, I'm already immune to it. From the moment I was born, my parents spoke to me about the Holocaust. When I refused to eat, they told me that in the ghetto there was no food. When I didn't want to sleep, they told me that during the war, the airstrikes woke them up from their sleep.' And she was right. We indulged her, but did not spare her our ordeal. On Holocaust Memorial Day, when her friends came to our house to watch all the terrible things that happened there on TV, they wept and Orit sat indifferent. I asked her, ‘Does this not make you emotional?’ and she said, 'I hear it from morning to night, from the moment I was born, you were feeding me stories about the Holocaust."

Sculpting his memories

Even before retiring, Willenberg worked a lot to commemorate the Holocaust. Teaching this subject to future generations was his life's mission. He painted and sculpted, lectured and spoke about Treblinka. The figures he created lived and breathed his past: the guard in the camp dressed up as a cantor; a poor Jew that the Germans ordered to make sure no one stays in the bathroom for more than a minute; a Jewish artist who painted, at the behest of the Germans, the false signs that were posted at the train station; a statue of an orphan girl hugging a loaf of bread; or a statue of the uprising in Treblinka - a pile of corpses, hats, clothing and tank parts all piled together.

"Igo always said, 'the sculptures will continue talking for me,'" his widow says smiling ruefully. "But whenever he decided to make a new sculpture, we would fight, because the bronze cost a lot of money, and each statue was at the expense of our trip abroad."

The sculptures were exhibited in museums in Israel and around the world. Only the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum had difficulty finding a place for them. "And Igo was very hurt by it," says Ada. "That is why when he sketched maps of Treblinka that he used when leading groups of students on trips to Poland, he was not willing to give them to Yad Vashem. Only after a lot of pressure and promises that the maps will be stored in the archives and the copies displayed on the walls, he relented. We came to the museum and saw that they made them into miniatures. Igo got angry and wanted to take them back immediately. I begged him not to cause a scandal."

In 1986, his book "Revolt in Treblinka" was released and later translated into eight languages. In 2014, the movie "The Last Witness" was released, portraying his life story. But more than anything, Willenberg dreamed of building an assembly hall for ceremonies and lectures where the camp had once stood, not far from the monument built by the Polish government in memory of the 900,000 victims.

"Igo always said, 'by the time this thing is built, I will no longer be among the living.' So two years ago, on the 70th anniversary of the Treblinka uprising, we bought a huge stone and placed it there as the cornerstone to the building that will come."

In 1988, the couple started joining youth groups and soldiers on trips to Poland. "The first time, we traveled with a group of urban students," says Ada. "When we returned to Israel, we decided we no longer wanted to travel with urban youth, because the students just did not know how to behave. Their parents paid a fortune for the trip, but the students thought they were going on vacation and on the plane, they started pulling stunts and didn't behave properly. We decided that if we were doing this voluntarily, then we'll only travel with Kibbutz youth, who worked and earned the money for the trip. And with them it was a delight - we arose at six in the morning, had a picnic in the woods to save money on restaurants, and when we got up from the grass, they cleaned up so that there was not a crumb left. We started accompanying urban groups only much later."

Recently, a suspicion arose that some of the travel companies worked to prevent the lowering of prices of the trip to Poland.

"It's a shame that these important trips are so commercialized. It's not just the trip itself that is expensive, but the hotels in Poland are very luxurious. Why do they need this? There are local security personnel, and cheap youth hostels that lower the expenses and teach the young generation humility."

Dozens of survivors pass away each month. The survivors are fewer, and so is the sensitivity to the distress some of them experience. "I am sorry to say that the attitude of foreign countries, like Poland and Germany, to Holocaust survivors is better than the Israeli government's attitude to Holocaust survivors," Willenberg says painfully.

"My husband and I didn't need help, but there are many survivors whose financial and health situation are terrible, and they pass away penniless and in shame. Some of them don't even have money for medicine and heating. While we were recently told that we did not have to pay for medication anymore, it is really too little and too late. In Poland, meanwhile, we are treated with respect and sensitivity. There, they live with the Holocaust much more than here. Perhaps they also feel guilty. We travelled to Poland a lot, not only to accompany groups but also for recreation and to visit friends, and have always encountered very positive attitudes toward Israel and the Jews. As someone who speaks Polish, I hear the locals talk about the young people: 'How beautiful are the youth, the girls are pretty.'"

It’s not easy to go on vacation to Poland.

"It was the Germans who planned the extermination camps in Poland, but the dirty work done by the Lithuanians and mostly the Ukrainians. Not the Poles."

One of those Ukrainians, John Ivan Demjanjuk, was acquitted in Israel because he could not be proven guilty.

"Igo did not appear as a witness in the trial since he did not see Ivan kill, because his shack was far from the gas chambers. But he did see him coming back in the evening to the wardens’ quarters. When they brought Demjanjuk to Israel and he saw him on TV, Igo immediately said: 'That's him, without a doubt, even based just on the way he walks.'"

A cool scooter

Even heroes weaken, and in the last two years of his life, the last survivor from the death camp felt it. He still had time to inaugurate the Museum of the History of Polish Jews. "The Polish president sent an airplane for the Israeli president and for the survivors, including us," Willenberg smiles. "And when we came back, it was hard for him to walk. We bought him a cool scooter, like a motorcycle, and he was driving it and feeling wonderful."

In his last year, Igo's medical condition worsened. A blood clot got to his brain and made it hard for him to speak or swallow. Then his situation started deteriorating on February 16, his birthday. "Igo died on February 19. We sat next to him and held his hand. We saw him close his beautiful eyes and stop breathing."

And now she's in mourning. "I had Igo almost until the end of my life, so I'm not complaining. He lived a full life until his final moments, leaving behind a daughter and three grandchildren. The funeral was also special. Crowds came, led by the president and the Polish ambassador to Israel. I keep saying: if Igo could see his own funeral, he would be willing to die again."

Yad Vashem said in response: "Yad Vashem's art museum only displays works that were created during the Holocaust, as well as of the artists that were murdered in the Holocaust. The exhibition 'Virtues of Memory' in 2009, which honored the artistic achievements of Holocaust survivors, a statue by Samuel Willenberg was presented, accompanied by his life story. In addition, three drawings of Treblinka camp that Willenberg created are permanently displayed in the Holocaust History Museum, which is frequented by more than 3,000 people daily."