Corfu and Me

One day the people of MyHeritage came to me and told me a story that I found hard to believe. About me.

1. The first call was made to my landline at work. Other than PR people who got the wrong number, nobody calls my landline at work. The speaker introduced himself as Roi Mandel and immediately started to tell me everything about myself. He knew the names of both of my parents, my grandparents, my mother’s sisters and brother, my wife, my children, the fact that the middle one had recently celebrated his bar mitzvah and that the eldest lives in America, my position in the company, my position at my previous newspaper, articles I had written recently.

It was spooky.

I asked him why he knew so many things about me. He told me that he was a researcher who had been sent by an American writer in search of her family history in Corfu. And somehow, since my mother’s family also has roots in Corfu, he eventually got to me. At this point I was convinced that this was some sort of a sting. As a condition for carrying on the conversation I demanded that he send me a detailed explanation, and especially proof of his existence and the veracity of his supposed job.

He responded that it would not be a problem. He already had my email address.

2. The tiny island of Ereikoussa is located about ten kilometers north of Corfu. It covers less than 4 square kilometers and has only one small town, also named Ereikoussa, and just a few hundred inhabitants. But this island harbors a secret kept for 70 years: during World War 2, one Jewish family was hidden there. A tailor, his three daughters and a little granddaughter. In the horrifying days of June 1944, when Corfu’s 2,000 Jews were gathered under German orders into the city’s old fortress and from there sent in boats, and later on trains, to their death in Auschwitz, the tailor and his family was hidden on Ereikoussa. First in the local priest’s tiny house and later moved between other safe houses.

All of the island’s residents knew the secret. You can’t keep a secret that big on an island that small. Certainly not when it's punishable by death. But nobody said anything. To a great extent, this secret remained hidden even 70 years later. Pride that was passed on by word of mouth but did not leave the borders of the tiny island.

3. Yvette Manessis Corporon is an American director and author of Greek origin. Her first novel, "When the Cypress Whispers", was based on the memoirs of her Greek grandmother from Ereikoussa. Among other things, it recounts the story of a Jewish family saved by the islanders. Following the success of the book, Corporon was often asked about the fate of that family. She didn’t have an answer. All her grandmother knew was that the patriarch was called Savvas. Not his surname. Nor the names of the daughters. Corporon consulted archives and experts at Yad Vashem, as well as surviving residents of Corfu, until she discovered that Savvas’ surname was Israel, the girls’ names were Nina, Spera and Julia, and the granddaughter was called Rosa. Julia, it turns out, passed away in Greece after the war, with no children. All attempts to find out what happened to the others led to dead ends.

4. Gilad Japhet was a curious child. The kind who likes to discover and learn new things. Among other things, he taught himself to read Greek. Since then he has managed to pick up five more languages, not necessarily of the kind that are taught here in schools, including French, Arabic, Italian and basic Turkish. 30 years later, however, it turned out that the Greek he voluntarily learned in his childhood would turn out to have dramatic importance.

Right now, even as he sits opposite me in his office, he seems frantic and restless. To his right there is a gigantic computer monitor, which can easily display a complex family tree with scores of branches. To his left there is a nimble laptop upon which he pounces at every opportunity to show me a key row in a huge spreadsheet, a ground-breaking document or an emotional thank you letter from a customer of MyHeritage, the genealogy website he founded 13 years ago and still manages today.

When Corporon approached his company and asked for their help in finding out the fate of Savvas and his family, Japhet took it as a personal mission. MyHeritage has access to a wealth of databases and old archival documents. Some are open to the public, after the company has digitized them and made them available for search, and some, private and disintegrating, it acquired access to and digitized. Japhet literally dove into the mountain of documents.

The first one he located was Nina. Of all of the women in Israel with this first name, Japhet found records of a Nina who immigrated to Israel from Greece after the war, and whose father’s name was Savvas. Then he found her grave in Kiryat Shaul cemetery. The father’s name written on the gravestone was Shabtai. So he realized that 'Savvas' had been hebraicized to 'Shabtai'. In order the find her sister, Spera, Japhet went on to combine detective work and linguistics. He assumed that ‘Spera’ could be ‘Esperanza’ in Spanish, or ‘Tikva’ in Hebrew. Through nights of searching, he went over countless records of women named Tikva who had immigrated to Israel from Greece, until he finally found one whose father’s name was Shabtai. What distinguished her from the others was her address, on Maor Hagola Street in Tel Aviv. Japhet remembered that Nina had also lived on that same street.

He intuitively assumed that a family of Holocaust survivors in the 1950's would try to live close to one another. Documents that he discovered later on confirmed that the Spera and Nina he had found were indeed sisters, the daughters of Savvas. He also found out that although they both married, neither of them had any children. Which means that Rosa wasn’t actually a granddaughter of Savvas.

5. My mother remembers Rosa, ‘the orphan from Corfu’, very well indeed. During her childhood she was often a guest at their house. In those days, anyone from Corfu who managed to escape to Israel after the war was considered family. They weren’t concerned about checking blood ties, and even if they had they would have found such ties between almost everybody anyway. The small and homogeneous Jewish community of Corfu had been intermarrying for hundreds of years. You wouldn’t have been able to get away from being married eventually to a cousin of some sort.

Some time after she arrived in Israel, Rosa Belleli, ‘the orphan’, was married. In the family photo from the wedding, nobody looks particularly happy. Especially not the elders, who knew her path to survival that had left her alive but without any family. At her side were Nina and Spera, who had raised her. Behind her stands a gaunt woman in a black dress without a hint of a smile on her face. That is my grandmother. Her name was also Rosa Belleli. The wife of David Belleli. My grandfather.

6. My grandfather was a short man. He was a carpenter, at a time when simple occupations were respected. Wearing a cap, his nails and the ends of his moustache yellow with nicotine from Ascot cigarettes, he sat in a little room allocated to him in the carpentry shop owned by my two uncles on Eilat Street in Tel Aviv, drinking stewed black coffee and expressing his dissatisfaction at the work of those who had inherited his trade. A powerful man whom all treated with respect, but who was already losing his stature. At noon the three of them would go to their flat in Kiryat Shalom for lunch (pasta peggiori, pasta fava, pasta spinaci, pasta ceci, or fish, depending on the day), and afterwards he would take a short nap on the green piqué fabric which was always stretched tight like drum skin on a hard mattress in his too-small bedroom, which had two separate beds in it. After that they would return for a few more hours to that wonderful place, with its smells of resin and sawdust and glue and the tempting and menacing saws that one of the uncles had already sacrificed a thumb to. My grandfather died when I was only 11 years old, so I assume that this description, precise as it may be, contains a smidge of nostalgia and mature hindsight.

I don’t have many personal memories of him. Maybe just that I was afraid to flush the toilet in the flat because of the terrifying noise that would erupt from the pipe, so much so that when I had finished using it, with the perpetual cigarette butt floating in it, I would turn on the tap and run away, and he would be forced to come and turn it off after me. And also that every time I went to his house he would pinch my cheek between his forefinger and his middle finger, in a carpenter’s pinch which made my face redden, and call me "vuz vuz", almost terrified of the all too white grandson he had produced.

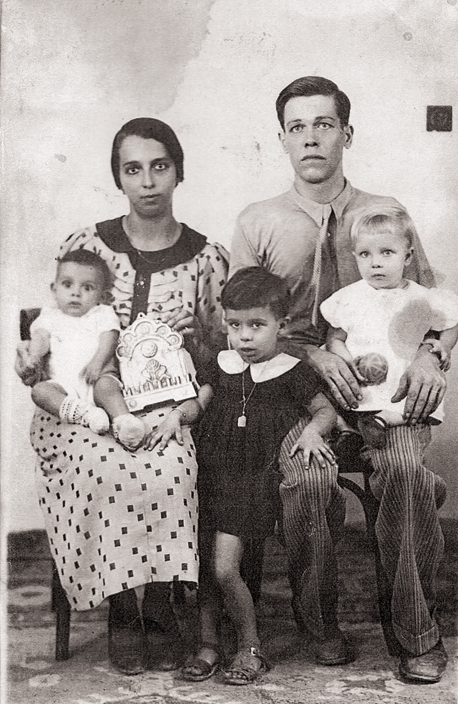

In truth I never imagined that I would ever revisit these memories, until the moment when in order to prove the honesty of his intentions, Roi Mandel from that spooky telephone call sent me an old photograph that staggered me. It shows my grandfather when he was a young man. He is just 33 years old, handsome and especially innocent looking, with that look young people have when they are still afraid of nothing and certain they can conquer the world on their own. He is sitting down but looks surprisingly tall, directing his chiseled chin and powerful expression at the camera, in pinstriped trousers, hair parted sideways, a collared shirt and tie, looking entirely European; a vuz vuz if you will. Next to him is my grandmother, who at young and old age alike remained loyal to the classic black-Greek look, and on their knees my two aunts and a baby who would one day become the carpenter uncle missing a thumb.

The photo rocked me. I assume that this was first of all because of the surprising appearance - I had never seen my grandfather so young. And obviously also because of the context - the photo, from 1937, was basically some kind of family passport. The young Zionist family, who had moved to Israel by itself from Corfu a few years earlier, was at that time considering giving up. The difficulty of acclimatizing, the language, the difficulties of trying to make a living and homesickness had broken them, my grandmother in particular. The photograph, it seems, was part of their preparation for returning. However things got complicated, and drawn out, and the situation got tense and a great war broke out. The sea was closed and they were forced to stay in Israel, not knowing that this would save their lives, but would also prevent them from seeing their parents, brothers or cousins who had remained behind in Corfu, ever again.

The wedding of Rosa Belleli ‘the orphan’. Next to her (in black) Nina who raised her, behind her (in black) my grandmother, also Rosa Belleli. None of those who knew her survival path look happy

But something else, highly meaningful, is concealed in this photograph. I have always loved my Greek side. It provided me with a Mediterranean label that I was proud of; the fabulously tasty food, Italian as the only language that everyone understood and that was always being shouted, the unconditional love, never speaking badly of anyone in the family no matter how distant, the healthy concern for the quality of the parmesan, the precise harvest date of the radicchio, the abundance of cousins who were always available to play with, and the total abstention from talking about feelings. And despite this, to a certain extent I turned my back on my heritage. In my stupidity I didn’t learn Italian, cooking well is something I'm attempting years too late, I haven’t reacquainted myself with distant cousins, feelings have become a key component of my life, I have never been to Corfu - a reasonably close destination - and I did not take part in trips led by family members again and again back to the house on the island that belonged to the family who was wiped out and was taken illegally after the war by a cousin without scruples. What happened, happened, that’s nature. Young people – as I once was - tend to leave the past to their parents. When you make a family of your own, you intensify the one you came from, but at the same time you grow distant from it.

Even now I didn’t chase the story, it was the story that chased me in the form of a black and white photograph that Mandel had sent me, when I had already believed him that he was indeed a senior researcher at MyHeritage. Suddenly it became clear to me that I can wish to leave behind whatever I want, it doesn’t really matter. A plot line that I didn’t even know existed continued to exist without requiring my wish or my acknowledgement, linking me ever so faintly with an orphan girl named Rosa, who seventy years ago was forced to leave her family in a rush to go and live with a tailor and his three daughters in a priest’s chamber on a tiny island, in order to survive. Her father, Peretz Belleli, was my grandfather’s cousin. They both left the same family with the intent of seeing each other again in the future. That didn’t happen.

7. When Gilad Japhet arrived at the home of the Hassid family in Rehovot, there was a large photograph hanging on the wall of an old man with a white moustache. He immediately identified Savvas, the Jewish tailor from Ereikoussa, and knew he had come to the right house. To his astonishment, the family had no idea who the mustachioed man looking over them was, other than the fact that he had been very important to their mother. Right up until she died, Rosa never told the story of her family, all of whom perished, nor the story of how she was saved. Japhet himself only reached the Hassid family after he insisted and continued to dig and research, until he located Spera’s step-granddaughter in America. She led him back to Rehovot, to the children of Rosa the orphan.

That was when Japhet completed the task he had taken upon himself with great success. He not only managed to find out what happened to Savvas’ family, but also managed to locate Rosa’s children in Israel, to amaze them with their mother’s story, and to bring them to an emotional reunion with Corporon the American, whose curiosity set this whole story in motion. Furthermore, thanks to all these discoveries, in June 2015, in a tear-jerking ceremony on the island of Ereikoussa, the Raoul Wallenberg Foundation presented the island’s residents with an award in recognition of their bravery during the war. It seemed that the circle was closed. But in many respects it had just been opened.

8. Nella Pantazi is a handsome Greek woman, impeccably dressed and serious in appearance. She is in charge of Corfu’s official archive, which of all places is located in the island’s old fortress, the one the Jewish residents were crammed into on the eve of their eviction. A long corridor meanders through the old building, which dates back to the Venetian period, and along its wall are thousands and thousands of folders, documents and testimonials, some of them hundreds of years old. Birth certificates, marriage certificates, death certificates, professional licenses and other documents of this kind. Pantazi controls all of these, knows them inside out, the sole supervisor of an enormous world of historical memories. Through her own good will over the past two years she has played a central role in an operation to reconstruct the history of the Jews of Corfu.

9. “From the moment that Savvas’ story ended, while we were still at the ceremony on the island, we had a feeling that we hadn’t really completed the story”, Mandel (36) tells me. “At that stage we had already presented a family tree of around 150 people, and we were very proud that we had managed to build such a magnificent tree for a family that for all practical purposes had been wiped clean from the pages of history. And yet, we had a great deal of archival material that we had acquired, and we hadn’t made use of all of it. We felt that if we didn’t do it, the chapter of history concerning the Jews of Corfu would simply be lost.”

"At this stage Gilad was already fully immersed in the story. He collected all the lists and data from Corfu and re-organized them to search for duplicates. And then he discovered the secret of the names that repeated themselves as synonyms. ‘Menachem’ for example, is also Mandolin or Mandolinos, and that is also Armando or Mando. Rina is also Irene, as well as Patzina and Pacina. He also discovered strict rules: the first-born boy or girl would be named after their grandfather or grandmother on their father’s side, the next after their grandfather or grandmother on their mother’s side, and so on. Once he had cracked that, the gigantic puzzle fitted together. After working through the night he added scores of people to the tree, and this way the tree of the Jews of Corfu grew and grew at an astonishing rate.

“He didn’t stop there, rather he continued to go over all of the testimonials in Yad Vashem that survivors had filled out in the years following the establishment of the State of Israel, and searched according to surnames. He searched for names of those who came from Corfu, and cross-referenced them with the information we already had. This way, the tree got even bigger. And that’s how he found your grandfather.”

Gilad Japhet (sitting) and Roi Mandel: “I bring materials, Gilad analyses them, and we keep going. I have become totally immersed in it; I can identify faces in photographs of dead Corfiots.”

10. Throughout the entire lengthy interview, Japhet is full of enthusiasm, but of a different kind than that of other start-up CEOs - and I’ve met quite a few of those in my life. He gathers himself onto the chair, a bit like a child who is trying to control himself at an official meal when instructed by his parents, but then he interrupts again with a pile of new information that he just has to share with me. He is 46 years old, graduated summa cum laude in software engineering from the Technion, married and father of three, who after a long career in the high-tech world across the globe had been asked by his family to rest at home for a while. In order to pass the time, he began to build his own family tree, realized that there was no software to help with this and wrote the first bit of code, which would eventually become MyHeritage.

He claims that he is now in the middle of an entirely personal journey to “save” the Jews of Corfu. The vast majority of them perished and can no longer be saved, but Japhet is driven by the feeling that if he won't uncover their fate, their history and the relationships between them, a highly significant piece of Jewish history will be erased. This journey has long deviated from the business need to promote the company, and has become a personal odyssey.

“This is destiny”, he tells me and describes with eyes ablaze how, “when it all comes to an end,” he will display the family tree of the entire Jewish community of the island. The tree he has built currently stand at no less than 1,934 people. A huge tree which began with a search for Savvas, and today the bottom row includes my children and others of their generation, and goes back eight generations, with branches that spread as far as Trieste and Alexandria, two cities to which about half the Jews of Corfu fled at the end of the 19th century following a blood libel - “a libel that through a twist of fate actually saved their lives,” he says.

“Nobody asked me to do this, there is no financial gain, and despite this I spend entire nights in search of more names and more links between the Jews of Corfu, deciphering how Greek names were Hebraicized, the meanings of nicknames, and the codes by which the children were named. Among the Jews of Corfu, and the Belleli family in particular, cousins married each other like crazy. That makes it easier to find them,” he smiles. “There is nobody today who knows and understands this community as I do. I feel an almost mystical connection to this community whose story was never told. And if I won’t do it then nobody will.”

As an Israeli, the Holocaust is highly responsible for motivating him. As a genealogist, it is a complex professional obstacle. “When you’re Jewish, when you look back you will always reach the ‘hole’, in both senses of the word, the point at which every genealogical sequence gets cut off.” I ask him if feelings of revenge push him forward. “I wouldn’t say revenge,” he answers, “but certainly defiance.”

11. A motivated archivist can give new life even to a vanished community. And the personal connection that Mandel developed with the archivist Nella Pantazi was a key the importance of which is hard to overstate in the reconstruction operation. “When Jews come to ask questions and search for documents, it’s a sensitive matter,” Mandel says. “The other archive in Corfu refused to cooperate, probably because of concerns about property claims. But Nella was willing to help. At first I asked her to find a document for us about Rosa’s brother, whom we knew had perished in the Holocaust. And as soon as she found it and sent it to us, I asked for his birth certificate. And then I asked for more documents about the Belleli family, and it went on from there. Each time I asked for a little more, one family after the other, until I felt comfortable enough to send her a long list and pray that she would agree, and she did. Nella is a fantastic archivist, a classic archivist for whom every document is important, and we managed to get her involved and give her a sense of the mission. I share with her the meetings I have had with people whose roots we have found thanks to her, and she becomes part of the story and helps with every document we need.”

Mandel is Japhet’s operational arm, responsible for continually providing pieces for the puzzle that Japhet is putting together. “Gilad sits with the tree, fills in what he fills in, sees what’s missing and comes back to me,” he says. “Sometimes he identifies a file that we didn’t receive from the archive, and Nella completes it. Sometimes I take what we have found and go to the families we have located in Israel, gain their trust, and they provide us with materials that they have. Documents, photographs, memories. Rosa’s sons, for example, let us dig through the photographs and documents they had at home, we made use of an old telephone book of their mother’s to call everyone on the list and ask, we received power of attorney to search Rosa’s official and medical documents. We also used pictures which had details written on their backs - dates, names, nicknames, greetings - to gather more and more information. I bring materials, Gilad analyses them, and we keep going. I have become totally involved in it; I can identify faces in photographs of dead Corfiots. Without intention and at a great diversion from our original goal, we have initiated a historical project, a full and comprehensive research on the Jews of Corfu. A great story which was never told and totally shook the lives of the people, and my life as well.”

12. MyHeritage is still defined as a start-up, but a strong one. Around 240 people work at their spacious offices on the top floor of a building in Or Yehuda, and around 40 more are located abroad, mainly in the USA. At any given moment in the ‘Tower of Babel’ room, there are scores of support staff providing online support in 42 languages, from Hebrew to Dutch, to members of the site who have stumbled across a problem with their family tree. It is considered the second largest genealogical company in the world after Ancestry, which was valued recently at $2.6 billion. According to the data provided by MyHeritage, the company has around 90 million registered users across the world who use it to build their family trees. Around half a million of these are paying subscribers, who bring in revenues of around $60 million each year, and have already made the company profitable. To date the company has raised $49 million, mainly from international funds, and its valuation is estimated at $350 million.

“Eventually there will be an exit,” Japhet tells me, “but the journey is more important. I am proud of the fact that I am doing something good, not just another toolbar or online gaming company. Money without values is not interesting. From my point of view, MyHeritage is a life’s work. Every person needs to know their roots, studies have shown that children who know their roots are more successful, because it gives them confidence, and I decided that I will help as many people as possible gain that confidence. That is ‘Tikkun Olam.’ Something very Jewish that is very important to me.”

13. The pursuit of information is actually what MyHeritage does. Snippets of information it gets its hands on about family relationships across the world are the resource it profits from. This resource comes in an inexhaustible supply which is constantly growing, but is also very scattered, inconsistent, inaccessible and to a large degree disappearing, thanks to humankind’s incredible ability to forget. In the competition between genealogical sites, whoever holds the biggest amount of this information and whoever enables users to connect these snippets easily, will reap the rewards.

That's why MyHeritage is investing a fortune and great efforts to accumulate more and more information. At the moment, for example, it is in the middle of a project to photograph all of the gravestones in Israel. “We hired six photographers, gave them cameras with GPS and sent them to photograph all of the gravestones in the 1,080 cemeteries across the country,” Japhet tells me. “It will cost us a million dollars, but it will provide great information. Every gravestone includes the full name of the person who died, the life span, the name of their father, sometimes the name of their mother and sometimes more information about them. This is a genealogical treasure trove. We use satellite photographs to scan the area to check that we haven’t missed any graves. Eventually we will know exactly where every grave is, and this is information that we will upload for free to the website. Furthermore we will digitize the information about the graves, enter it into the database and that will allow us to fill in lots of missing pieces of information.” According to the company’s estimation there are around three million gravestones in Israel, and up until now they have photographed about one million of these. At a rate of one hundred thousand graves per month, the project will be completed by the end of 2017.

As part of the desire to expand to more and more countries and to gather information, Japhet has conceived, and his team has developed and integrated, algorithms in the website which enable the online translation of names in family trees. So, for example, a customer of MyHeritage in Israel, who has constructed their family tree, can search for relatives in Argentina who can be found on family trees in Spanish, and at the click of a button can merge these into a cross-continent tree. Likewise, a customer in Poland can access information about gravestones, which will be translated into their language.

Google’s book-scanning project has also provided a wealth of archive data for MyHeritage. The company selects hundreds of thousands of books with family history value, and uploads them onto its website. At this stage, using the specialized technology it has developed, data about two billion people which has been entered into family trees by users, is semantically cross-referenced with the free text found within the hundred million pages of books which have been uploaded. When a match is found, the users receive the relevant excerpts from the books, which describe their relatives. “Gilad spent weeks reading hundreds of old books and analyzing them, and then founded an expert system of rules on which the system is based,” says Mandel, “and this invention has so far yielded 80 million discoveries for our users."

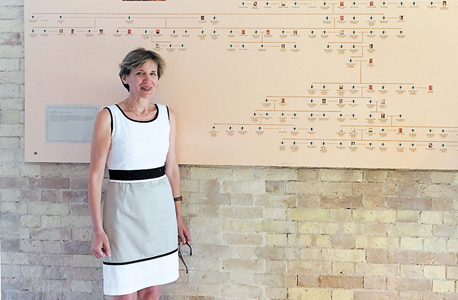

Nella Pantazi, with a family tree in the background. Credit: Roi Mandel

And as the world is ever so wide and the funding available, so are the inventions for collecting genealogical information. MyHeritage’s latest project, to map the remote tribes of Papua New Guinea, has been in the news lately. Japhet explains that the project aims in fact “to map and document tribes whose culture is at risk of becoming extinct. Magnificent, traditional tribes who have preserved their own structure, culture and rituals for thousands of years, but whose young people in our day and age are looking to the West and abandoning the traditional structure. Our teams travelled to Namibia as well as to Papua New Guinea, spent a month living with the tribal people and documented everything they could, built family tress which include history and culture, and scanned every available document. We have preserved and documented this information for posterity and for the future generations of these tribes.” Since in wild regions of Namibia there is no writing on graves, he says “our researchers simply went with the elders of the tribe from grave to grave, wrote on a white board who was buried in each place, photographed the board next to the grave, and then erased it and moved on to the next grave. This is information that unless we document today, will disappear forever in the next generation.”

“History,” says Japhet, “never ends. Myths need to be verified or refuted.”

14. What was young Rosa doing on the island of Ereikoussa, away from her home, with people who were not even her immediate family members? The assumption is that Rosa’s father had also been a tailor, and she had joined Savvas the tailor and his daughters in order to bring a delivery of clergy clothes to the priest of the island. While they were there, the priest of Ereikoussa advised them not to go back because “something was happening in Corfu.” This is how Rosa joined her new ‘family’, and was permanently separated from her immediate family. But that is just an assumption, which will probably remain so forever. Sometimes history, even after thousands of documents and clever software algorithms, cannot be verified or refuted with certainty. Myth also has its place.

Shelves in the Corfu archive. “Nella is a fantastic archivist, a classic archivist for whom every document is important, and we managed to get her involved and give her a sense of the mission.”

15. At the end of the interview Japhet places a document in Greek in front of me. “This is your grandmother’s birth certificate, we found it in the archive in Corfu,” he tells me. What does it say, I ask him, and he translates: “Isaac Baruch, son of Marcus, aged 32, carpenter by profession, resident of Corfu. Presented to me a baby girl who was born on Tuesday, November 3rd 1910. Daughter of Sara, who is the daughter of Menachem Vivante. The baby was born in Corfu and was given the name Rosa. The two witnesses: Mandolin Moustaki and Solomon (surname not clear), teacher by profession.”

A journey in time. Saturday morning, aged 19, a tired soldier wakes up too early in a room in his parents’ house, to the sound of shouting in Italian emanating from the living room. Rosa Belleli, almost entirely deaf, is sitting and folding laundry during a too-lively conversation with Yolanda, an ageless relative. She diligently folds a top and then rises, pushes the top under the cushion of the armchair, and sits back down on it. This continues with a pair of trousers, a shirt, underpants. All are folded carefully and immediately undergo gravity-based ironing, as far as a slender Greek woman over seventy is able to do. The tired soldier gives his mother an angry look, and she, out of respect for her mother signals to him that nothing can be done, and out of love for her son immediately feels guilty.

Japhet, apparently more than most people, understands the power embedded in the physicality of information. The power hidden in the piece of paper he has put in front of me, a document that was taken out of a sealed archive, even if the information in it does not hold anything new. Just a piece of paper signed in Greek, and yet instantly provides another dimension, turns my grandmother from somebody who existed when I was born and became a memory after she died, into someone who had a father and a starting point in life. In basic terms she became someone quite like me. Like all of us. And then he lets me sink further into more memories.

[email protected]