Recalling a final Rabin interview

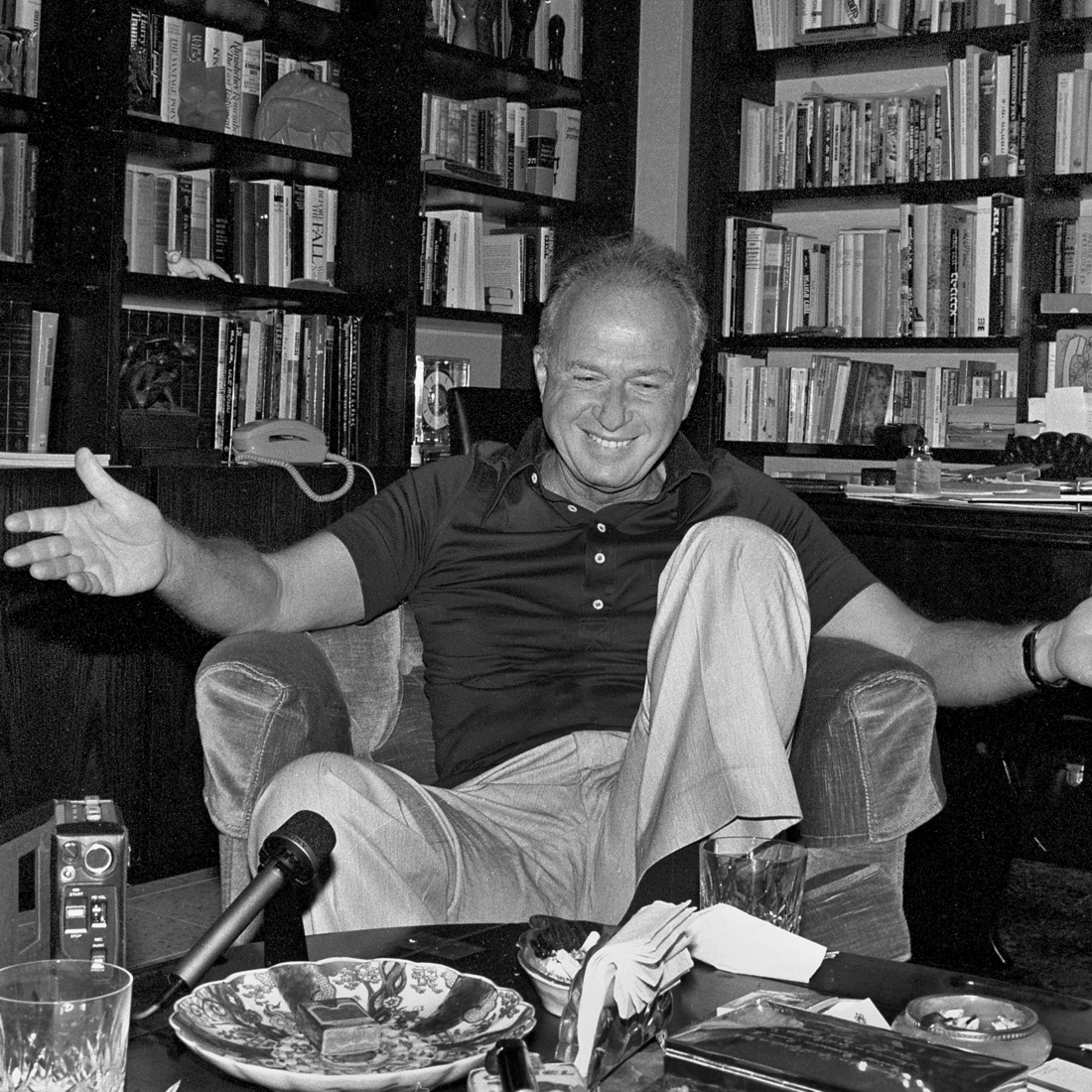

Covering YItzhak Rabin for Yedioth Ahronoth for years as a political correspondent, Shlomo Nakdimon recalls his relaxed interviews with the prime minister in his Tel Aviv living room, where Rabin spoke of his relationships with the political and military elite and defines what victory is just months before his assassination.

When he was still just a Knesset member, he hosted me in his Ramat Aviv apartment in Tel Aviv—not far from where I lived—once every two weeks, on Wednesdays. In those meetings, Rabin was at ease, after having taken a bath, wearing a bathroom and sinking into the armchair in his study and reminiscing about the past.

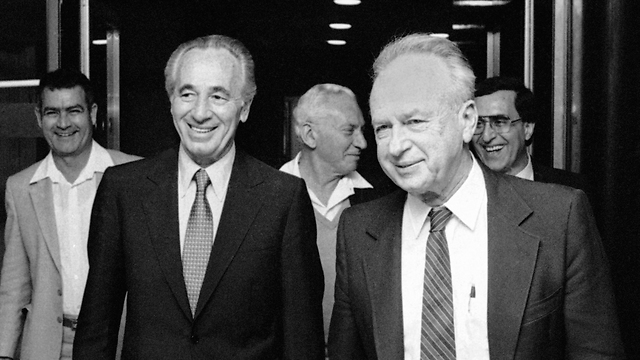

It was impossible to have a conversation with Rabin without also discussing his forced-partner in the state's leadership, Shimon Peres. Once, Rabin divulged that this was "Leah's responsibility," leading me to understand that it was his wife who kept a file on his rival. When I asked to look at the file Leah was keeping on Peres, Rabin told me to speak to Leah. But that file had never been opened, and it would be interesting to learn where it lies today.

On April 17, 1995, when he was the prime minister and defense minister, Rabin agreed to my request—made through his advisor Eitan Haber—to have a series of conversations to fill in the holes in the tale of his political career. The first of these conversations lasted 50 minutes, and we agreed to meet again from time to time. But seven months later, three bullets put an abrupt end to the leader's work—and to our conversations.

The fight before the war

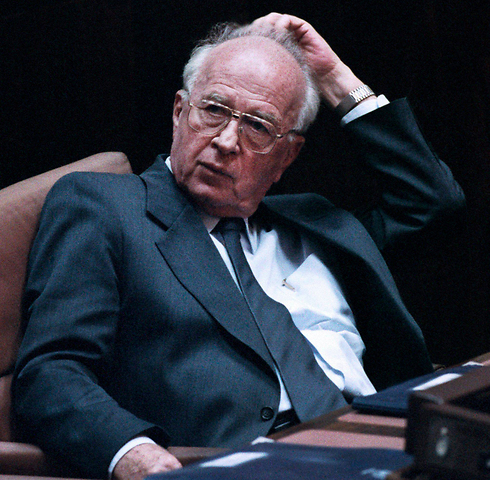

As the IDF chief of staff, Rabin built a glorious army. Many experts view the General Staff under his command as the best the IDF has ever had. The prime minister at the time, Levi Eshkol, was seen as a good prime minister and a good defense minister, but also as one who lacked military experience. In that situation, Rabin served as Eshkol's chief military advisor.

The three weeks of wait that preceded the 1967 Six-Day War were accompanied by a complex diplomatic process, but even more so by an open, serious confrontation between the political leadership and the top military echelons.

"On top of the busy and hectic daily schedule, I asked to hear what experienced men like David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Dayan"—who was Rabin's political rival at the time—"and minister Haim-Moshe Shapira had to say," Rabin told me.

"I expect to find the same Ben-Gurion from his glory days. Someone who—despite his age and distance from the centers of activity—still projects authority. But that's not what happened. He gave me a hard time. He wasn't familiar with the information. Passed terrible criticism on the prime minister during one of the nation's hardest moments—and done so in front of me, a subordinate to the prime minister. He said the big recruitment of reservists was an error. He slammed: 'The state was put in a very grave situation. You shouldn't go to war without a significant partner.'

"When I spoke to Dayan, I found a great appreciation for the IDF and a counterbalance to Ben-Gurion's blunt criticism. I wanted to hear from Shapira why he so adamantly objected to a military operation. His opinion was in line with that of Ben-Gurion's. How did I dare go to war when all of the conditions are stacked against us? No other bothered to tell me that Rafi's (Israeli Workers List) secretary general Shimon Peres, sent by Ben-Gurion, suggested to the party leaders that the only way out of the situation was to entrench ourselves until we can find another country to aid us.

"In effect, I was made to be the main person to blame for the situation Israel found itself in. I knew the IDF was built well, properly prepared. And there I was hearing, mostly from Ben-Gurion, that this good army that was prepared on our borders was actually an obstacle that dragged us to this escalation.

"I was looking for someone to have a heart-to-heart conversation with. Ezer Weizman was, at the time, the number 2 man in the IDF high command. I had a special relationship with him. I asked him to come to my house. Thinking back on it, I think something of the harsh things said to me by Ben-Gurion and Shapira must have registered with me as possible. I told Weizman that maybe I was part of the reason Israel was in this situation. And then, consciously, I asked Ezer, 'Perhaps I should step down?' Had I resigned, Ezer would've received command. But he actually calmed me down. He told me 'Don't think of stepping down. Rest, relax. You'll see, you will lead the IDF to a great victory.

"Leah called the chief medical officer, Dr. Elyahu Gilon, who determined I was suffering from exhaustion. He gave me a sedative that made me sleep until evening time the next day. When I went back to work, I had my full strength. I told Prime Minister Eshkol what had happened, and told him that if he thought my resignation was required, I would accept his decision."

From the Altalena to the premiership

Israel's 17th government, led by Rabin, only lasted for two and a half years. His inexperience was to his detriment. There was no harmony among the government's leading trio—Rabin, Foreign Minister Yigal Alon, and Defense Minister Peres. In the next election for the 9th Knesset, Likud, led by Menachem Begin, won. Weizman, who was the head of the Likud's campaign, was chosen to serve as a defense minister in Menachem Begin's government. On June 21, 1977, Rabin passed the baton to Begin.

"You're asking me how I felt? You can imagine," Rabin told me. "But we must follow the will of the people. I walked Begin to his office which was, until that moment, my office. And in that both he and I followed the will of the people.

"And then, on the way home, the events of the Altalena Affair came flooding back—29 years and a day before, on June 22, 1948. I'll repeat to you what I've always said, both verbally and in writing: When my men at the Palmach headquarters—close to where the ship docked—heard Begin was on board, they believed it. And they opened heavy fire, at tremendous intensity, from all weapons, towards the ship. At once, all of the hatred the Palmach and Haganah felt towards the rebels and their leader found a release in the intense fire. We weren't feeling the joy of winning. We were following an order. After we received an order to arrest the commanders of the Etzel, primarily Begin, I headed a company of armored vehicles to follow it. We couldn't find him.

"And now, I was passing the premiership on to him. We didn't have a personal rivalry. Many years later I was thinking whether all Begin meant to do was really just enrich his fighters, who are now part of the IDF, with additional weapons and ammunition. What can you do? At the time we thought—and so we've been told—that there was a rebellion against the government."

A dangerous adventure in Iran

The 21st government was formed in September 1984, led by Shimon Peres (who defeated Rabin in the primary election for the party's leadership) as part of a rotation agreement with Yitzhak Shamir. Rabin was appointed the defense minister under both of the prime minister. It was the midst of the Iran-Iraq War, with Jordan serving as the main supply line for weapons and food to Iran.

"The tendency was to hope the war continues and that no side wins," Rabin told me when asked what Israel's politcy was to the two warring sides. "Let brother kill brother. When I started the position, there was a situation in which the previous Israeli governments—led by Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir—have agreed to provide, in indirect ways, arms to Iran—even though they knew this was Khomeini's regime. The arms deals were mostly for different kinds of weapons and mortars, which brought nice profits to the defense industries. It was a time of prosperity for the Israel Military Industries and Soltam Systems. Despite the arms embargo the US and its allies placed on Iran, all sorts of players provided Iran with arms—not just Israel. This was an Arab country, Iraq, fighting against a Muslim non-Arab country, Iran, and almost the entire Arab world supported Iraq.

"Yaakov Nimrodi, the former IDF attaché to Tehran, and Al Schwimmer, the founder of Israel Aerospace Industries and a recipient of the Israel Prize, proposed to sell Tau missiles to Iran. I—mostly I—argued that we were enjoying generous American aid and that according to US law, we couldn't export American weapons and technologies sent to us as the end user. For that reason, I was unwilling to risk the American aid for all kinds of escapades.

"So the three of us (Peres, Shamir and Rabin) sent the Foreign Ministry's director-general, David Kimche, to the US National Security advisor in Washington, Robert McFarlane, to request approval for the deal. Kimche recommended to McFarlane to bring in Secretary of State George P. Shultz, and McFarlane did. Our contact with the Americans was Oliver North, an operations officer in the National Security Council.

"Kimche came back with McFarlane's approval, and then we sent some 500 Hawk missiles (to Iran), without launchers because the Iranians already had those from the Shah's regime. At the heart of the matter was the American desire to free four hostages for the weapons. But there was also the question of how were we going to get those missiles back. (The Americans) promised to find a solution somewhere in the CIA/Pentagon/National Security Council triangle. And then Amiram Nir, the prime minister's advisor on terrorism, suggested to me that the Americans take over providing aid to the Iranians, which will get us out of the conundrum of having Nimrodi and Schwimmer getting money from the Iranians...

"And so we did. I saw Amiram as the man who really saved Israel's relationship with the United States... had we kept trading (with the Iranians) through Israeli contractors—who also believed this could be an opening for business with Iran—this entire thing would've become an Israeli-American crisis. Everything we invested in this, both weapons and money, we got back. Not only did we not come out with nothing, we even stood to gain. We got Tau missiles that were more advanced than what we sent the Iranians."

It's important to note that in addition to Rabin's recollections of the affair, which shook the American administration, many of the other individuals who were involved shared their own memories, and there are significant differences between their versions.

Defining victory

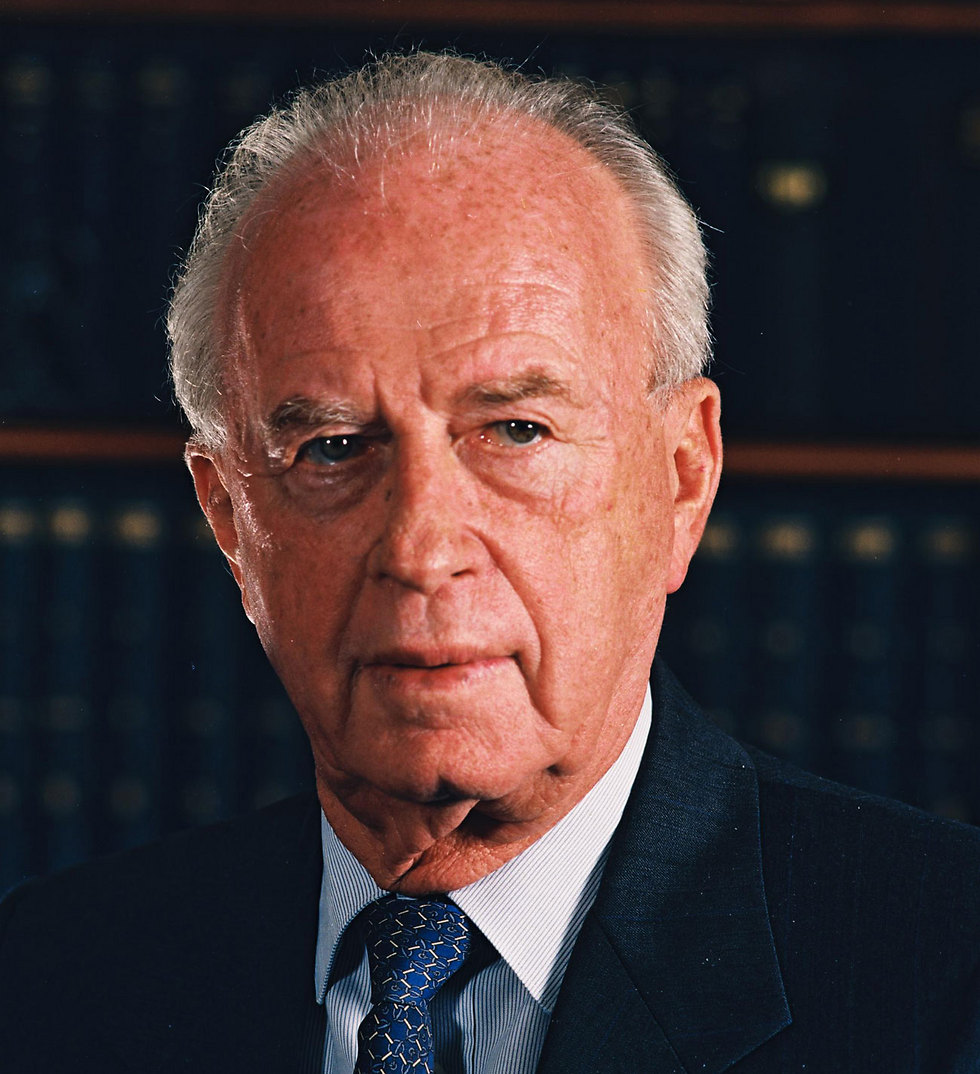

The things that Rabin said in our conversation on April 17, 1995, on what he learned from the Gulf War resonate to this day when we ask ourselves what are the limitation of Israeli force, what is the ability to endure and what is victory.

"The threat analysis showed that the Arab world, Egypt, Syria and Iraq, were going for surface missiles," he said. "Arming themselves with those began in the early 80s. I asked myself, 'What's our response to missiles?' It was clear that a new threat had been created that hadn't existed for Israel since the War of Independence.

"In my recollection, there's the following story: In the middle of the 50s, I was a member of the General Staff as the head of the Training Division. The General Staff presented situation reports to Ben-Gurion. When the prime minister asked the commander of the Air Force about the danger of air raids on Haifa and Tel Aviv, members of the General Staff treated it pretty dismissively, meaning that it wouldn't influence the course of the war.

"Then Be-Gurion got angry and said a sentence that is engraved in my memory to this day: 'I was in the German blitz on London; you weren't. I don't want to put the Israeli home front to the London test.' That's what is engraved on my memory.

"Then, in the threat analysis, I said what our response would be. In my view, as for the Iraq-Iran missile war, we went to the Americans and said, 'We're not big; give us rockets, the ones that you call tactical, and for us they're strategic.' Thus began the development of the Arrow missiles.

"The Gulf War proved to the Arab world that the home front is the Achilles' heel of the State of Israel."

"The scuds, we know, weren't a precise weapon for military purposes, but it did wake up the home front. We didn't know what the impact of an awakened home front on the endurance abaility of the country and on the soldiers' ability to fight on the front line, and we had to give responses, both offensive and defensive. This describes a dangerous war.

"I asked myself after that war what the difference was: We had to achieve victory not in 42 days, since Israel couldn't allow itself an intensive month-and-a-half-long war. We had to achieve victory in less time, between two weeks and three. A long war is necessarily fraught with the danger of losing to those against whom we'll have to have an all-out war, now or in the future.

"For me, winning means breaking the enemy's force in a manger that will cause him to ask for an immediate ceasefire, with our having a strategic threat against him and his not having one against us. There's no other victory in a conventional Arab-Israeli war."

Conclusion

I had a lot to ask the prime minister, and I was impressed that he wanted to break down so many issues from so many fields. But after 50 minutes, Rabin had another meeting that he had already set with Channel 2. We said goodbye. His handshake was, as usual, limp. We agreed to additional meetings.

"Eitan will schedule," he said to me. But the Jewish assassin's bullets ended the historic collection of information from the mouth of a man whose honor is deeply ingrained in Israel's collective national memory,.