The non-kosher conduct of kashrut supervisors

Complaints against the dubious activity of kashrut supervisors from Jerusalem’s Religious Council have led to dozens of testimonies from all across the country. These reports include threats, blackmail and nepotism, raising serious suspicions of criminal activity and tax offenses worth millions among kashrut supervisors and those in charge of them.

The biggest threat to a business owner in Jerusalem is the revocation of the business’ kashrut certificate. In a city where 80 percent of Jews define themselves as ultra-Orthodox, religious, or traditional, a business without a certificate is doomed. There is no wonder, therefore, that many of Jerusalem’s business owners were afraid to talk to us. “Forget it, I don’t want to get in trouble” was the common response.

Nevertheless, there were a few who agreed to talk, and their stories raise a troubling image: Alleged extortion by supervisors demanding black money; a curious demand to purchase products only from certain suppliers; and an incessant effort to put pressure on them to pay more, as well as to give in to the most radical Jewish denominations.

One such story happened to Hotel Yehuda in Jerusalem last Passover. Several dozen guests, mostly moderate religious Jews, gathered at the dining hall of the hotel for a Passover Seder. Around tables filled with food, they listened to the story of the Haggadah from the rabbi and used, at the guests’ consent, a “Shabbat-friendly loudspeaker”—a sound system developed by the Zomet Institute that does not desecrate the Jewish day of rest and holidays.

Several days later, a senior inspector from the Jerusalem Religious Council’s kashrut department showed up at the hotel, moved the regular kashrut supervisor out of his way and took a thorough tour of the place.

“They were angry at me for approving the loudspeaker, so they sent the inspector to search for problems,” the supervisor said later on. “He entered the kitchen and started looking underground. The hotel does everything according to the Halacha, but not the way the Religious Council wants things to be done. It’s about honor.”

The story did not end here. Shortly afterwards, Rabbi Shmuel Burstein, deputy head of the Religious Council’s kashrut department, called an urgent meeting with the hotel’s general manager. He made it clear that while he was aware of the fact that the council was not authorized to revoke the hotel’s kashrut certificate over the loudspeaker, there are other ways it can get its way.

“The High Court can tell me, ‘Don’t intervene’ in the loudspeaker affair,” the rabbi said, “but by the book I can take away your certificate over every mixing of spoons (for meat and dairy).” Later in the conversation the rabbi blurted, “At the end of the day, it’s better to be friends than to be enemies.”

“They wanted to bring me down,” says the general manager, Yishay Barnea, who left the conversation feeling threatened. “One of the interests of the council is to create fear. Their world view includes an approach that once business owners are afraid, they will be scared to do things (the council) doesn’t approve of.”

The Rabbinate’s long arm

Israel’s kashrut procedures are determined by the Chief Rabbinate, but they are enforced on the ground by the local religious councils. Each council is responsible for the businesses in its jurisdiction area, which are completely at its mercy.

“The city rabbis and the regional rabbis essentially serve as the long arm of the Chief Rabbinate,” the Rabbinate’s website states. In practice, however, each local religious council does as it pleases, setting its own kashrut laws, sometimes in complete contradiction of the Chief Rabbinate's definitions. The use of a Shabbat loudspeaker, for example, is permitted in Tel Aviv but forbidden in Jerusalem.

While the Chief Rabbinate is trying to tighten its hold on the local councils, the local rabbis are refusing to give up the major power they have been given. “The councils have power and can do whatever they want with it,” says Knesset Member Rachel Azaria (Kulanu). “There is no supervision, there are no rules. It’s a complete monopoly, and they do what they want. The business owners are a captive audience.”

The most difficult religious council is probably the one in Jerusalem. Barnea, the only hotel manager in the city who agreed to talk openly, knows a thing or two about kashrut. He is a religious Jew who was born in Bnei Brak and ran one of the Haredi sector’s biggest banquet halls in the city for years. In addition, as chairman of the Jerusalem Hotel Association, he has often received complaints about the local religious council overstepping its authority.

“Not so long ago, I received an appeal from a large chain that has a hotel in the city with a playground in it. On Saturdays, the guests’ children engage in crafts, using scissors, among other things. The supervisor ordered them to stop because it is forbidden to cut on Shabbat. What does that have to do with the kashrut of the food? They are ignoring the fact that a considerable part of our target audience is made up of foreign tourists, gentiles and, yes, even seculars.”

“The monopoly corrupts,” adds Israel Hotel Association Director-General Noaz Bar-Nir, “and creates a lot of negative phenomena.”

Only last July, Jerusalem Police investigators raided the religious council offices in the city, arresting five employees on suspicion of abusing their power and received bribes from supervised bodies. About a year ago, it was reported that the family members of the council’s chairman serve as supervisors against the orders of the Ministry of Religious Services.

A 2009 State Comptroller report also criticized supervisor employment methods, as well as the way they are inspected and trained. A source in the religious council itself told us that even today, “supervisors visit businesses once every two months, instead of every 10 days.” Such claims were also raised by business owners who agreed to be interviewed anonymously.

In addition, the state comptroller was irritated by the fact that some employees provide private bodies with kashrut supervision services while working at the religious council. This finding, by the way, did not stop Rabbi Burstein himself from providing private kashrut services to the Caesar Premier Hotel in Tiberias, as well as to other hotels in the Dead Sea.

Another common phenomenon in Jerusalem, according to some business owners, is paying supervisors under the table. “When I first opened the restaurant, we were visited by a kashrut supervisor who suggested that we pay him under the table,” says the owner of Jerusalem’s Topolino restaurant, who recently moved his business to Tel Aviv. “He said that was the acceptable way. We said that was not the way we worked. Not paying him under the table made the payment more expensive of course, but we were unwilling to take the chance, both legally and ethically.”

Were you surprised by his offer?

“No, not at all. The entire system works that way. We were unusual in this case.”

Another business owner confirms the story, saying that he also received a demand to pay a kashrut supervisor under the table, otherwise he would be forced to pay more.

“That’s how it works in the city,” he says. “Everyone knows it, but everyone is afraid to go against the Rabbinate, which could revoke your kashrut certificate and terminate your business, so you just grin and bear it.”

Another claim, made by several business owners in Jerusalem, has to do with the wholesalers that they are allowed to purchase goods from. “Ask the business owners if they were able to change their supplier,” says a business owner in the market. “There will be someone who will make it clear to you that you must only buy from a specific supplier, or else.”

Why?

“Figure it out on your own.”

Yeshayahu Yishai, head of the Jerusalem Religious Council, recently got into trouble when it turned out that he also works as a private slaughterer for commercial companies that import meat. “As part of that job, he can say to a restaurant or a hotel in Jerusalem: ‘Listen, from now on you can only use the meat imported by the company I work for,’” says a well-informed source. “It creates a conflict of interest.”

About three weeks ago, the Chief Rabbinate’s legal adviser sent a warning letter to Yishai, making it clear that because of this conflict of interest, he must stop working privately or at least publicly declare that he is precluded from dealing with kashrut matters within Jerusalem. Yishai has yet to read the letter. He was in South America, on a business trip, when it was sent.

Doing business ‘like in the underworld’

On the eve of Passover, a moment before the high season for Jerusalem businesses, a kashrut supervisor paid a visit to several businesses in the city center that he is charged of. “Pay me under the table,” he demanded.

“I’m sorry, we work in an organized manner,” the business owner replied. “We only pay against an invoice or a pay slip.”

The supervisor left and the next day, the business owners and their workers received a visit from the same supervisor’s inspector, one of the most senior officials at the Jerusalem Religious Council. He entered the kitchen and started screaming and running wild. “You won’t get a kashrut certificate for Passover,” he roared, adding: “If you don’t settle the issue with the supervisor, your certificate will be taken away.”

“We can’t work that way, it’s illegal,” the business owner replied. “Come to my office for a meeting tomorrow,” the inspector said before leaving.

Another day went by, and the businss owners arrived to the inspector's office at the Jerusalem Religious Council. The senior inspector closed the door and put the supervisor on the line so he could "mediate” between the parties. “You have to understand,” the inspector told them, the supervisor "has no way of receiving a pay slip. He is unfortunate.”

“What exactly are you asking us to do?” one of the business owners wondered. “We can’t work that way.”

“That’s the way it is,” the inspector explained. “That’s the way he works. Pay him, or you’ll be left without a Passover kashrut certificate, and without any kashrut certificate at all.”

The business owners were in a bind. They realized that without a kashrut certificate at such busy period, their business will suffer a critical blow. Any way you look at it, it’s blackmail.

“I felt like this was an arbitration in the underworld,” one of the business owners says in retrospect. “I assume that the story in this case, like in many other cases, is that the supervisor is registered as a yeshiva student or as unemployed and he wants to have the best of both worlds. We business owners are left with no other choice—if we refuse to cooperate with these criminals, our businesses will collapse. It’s time to clean rid the system of this poison.”

We heard similar stories from other business owners in Jerusalem. “Apart from the blackmail issue, think about the economic issue: This is tax fraud for all intents and purposes,” one of them says. “The state loses tens to hundreds of millions of shekels here every year, due to money under the table, which goes to people that the state forces us to work with. It’s absurd. The supervisors have the legitimacy to extort us and demand high sums, sometimes backed by the Rabbinate, and these costs are eventually charged from the customer because we have no other choice.”

The inspector in question denies the allegations against him. “There was no such thing,” he says. “I never approved payments under the table, so I don’t understand what this is about. The day after tomorrow there is going to be a bid for head of the marriage department, so there may be good friends who want to speak ill of me. I know there are areas where these things (money under the table) are discussed, but I never approved such a thing.”

Selective enforcement

When it comes to the Haredi sector, the Rabbinate monopoly is actually not as threatening. The kashrut institution that controls Jerusalem’s Mea Shearim neighborhood is the Badatz Eda Haredit—a private kashrut body for communities that won’t settle for the Rabbinate’s kashrut rules. According to the Law Against Kashrut Fraud, a Badatz certificate can only be presented if the business already has a kashrut certificate from the Rabbinate, and both certificates must be presented openly.

Every year, Rabbinate inspectors hand out some 800 fines over violations of the law across the country, but it seems that none of them has ever visited Mea Shearim. A tour of the Haredi neighborhood revealed that many businesses present themselves as kosher using a Badatz Eda Haredit certificate only. We were unable to find a single kashrut certificate from the Chief Rabbinate.

“I have never seen Rabbinate inspectors here,” we were told by a worker in one of the cafés at the entrance to the neighborhood. “Legally, I know that we need a Rabbinate certificate, but we don’t have one.”

In other areas, however, kashrut inspectors are working in full force.

Yehonatan Vadai is the owner of Carousela Café in central Jerusalem. Upon opening his business in 2009, he too was shocked when the kashrut supervisor demanded to receive his payment under the table. After agreeing for lack of any other option, he was even more surprised to see the supervisor arrive just once a week. “I didn’t understand what I was paying for. Just for the certificate? It was like a protection racket,” he says.

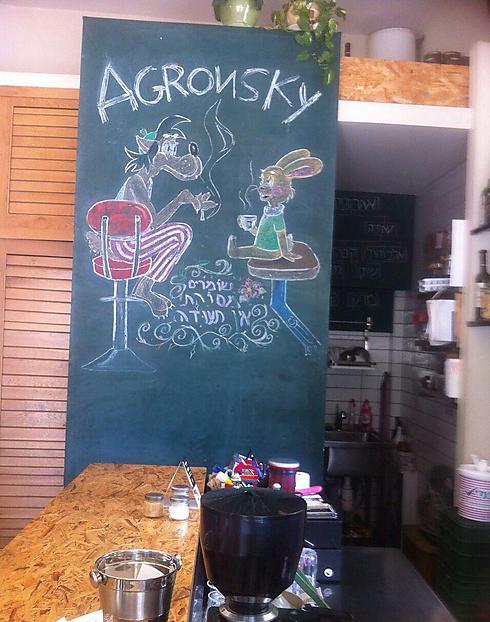

Vadai decided to break off contact with the Religious Council and began presenting his business as “kosher without a certificate.” The initiative was joined by other restaurants in the area, which were all slapped with a NIS 1,000 ($265) fine by the Religious Council.

Following the incident, and with the encouragement of MK Azaria, Rabbi Aaron Leibowitz introduced the “private supervision” initiative, which provides private kashrut certificates in a communal spirit. The Rabbinate was unimpressed and kept fining the restaurants with the alternative certificate, prompting Vadai to petition the High Court of Justice. The court rejected his appeal, but the three-judge panel did criticize the Rabbinate.

Almost everyone agrees that the problems stem from lack of transparency and supervision. Under the law, the council members are elected based on an agreement between the local authority, the local rabbinate, and the religious services minister. The problem is that these bodies often fail to reach an agreement, and in such a case the law states that the council members will be appointed by the religious services minister.

When that happens, the council members’ loyalty is to the minister who appointed them rather than to the residents they are supposed to serve. Only recently, for example, Shas leader Aryeh Deri, whose party controls the Ministry of Religious Services, announced a major salary increase for religious councils’ heads. About half of the 131 people enjoying this benefit were directly appointed by the minister. (Officials at the Ministry of Religious Services explained that the move was aimed at fixing a decades-long injustice).

The Ne’emanei Torah Va’Avodah movement, which works to advance liberal Jewish values, is trying to change this situation. “The religious councils’ inadequate function in the area of kashrut and in other areas stems, among other things, from the structural problems of the religious council,” explains Tani Frank, the movement’s religion and state projects coordinator. “The main problem is that in most councils there is no public supervision on what is going on, and so cases of corruption frequently develop unhindered.”

The movement teamed up with MK Aliza Lavi of Yesh Atid, who recently submitted a bill limiting religious council heads’ term to five years (at the moment, their term is unlimited), thereby giving the local authority more power in the selection process of religious council members.

“The bill will create a situation that each religious council will be selected by public representatives in the local authority, who will supervise what takes place in the council,” she says.

Supervisor raises his own salary

Several weeks ago, the kashrut supervisor of the Tamara butcher shop in Ramla showed up and informed the owners that his monthly wage was going up from NIS 500 ($132) to NIS 750 ($198), and that there was no point in arguing. Moti Suleimanov, the shop manager, was amazed. “It’s unjustified, and I have no intention of paying that amount,” he says. “The supervisor only comes here occasionally as it is, sits here for two minutes and leaves. He doesn’t do anything!”

At the same time, more and more business owners in Ramla have been receiving demands, out of the blue, to double and even triple their kashrut supervisor’s monthly salaries. “It feels like we’re dealing with a criminal organization, one of them says.

The owner of a restaurant in the city says that his kashrut supervisor recently demanded a raise from NIS 600 ($156) to NIS 1,500 ($390) a month. “I can’t afford to pay such a sum,” he says. “The supervisor arrives from time to time, drinks a glass of coke and leaves. He doesn’t even check the place, he doesn’t look.” Only after being threatened that his kashrut certificate would be revoked, and following long negotiations, the restaurant owner managed to reduce the supervisor's monthly wage to NIS 1,000 ($260).

The problem lies in the fact that the kashrut supervisors are funded and inspected by the Chief Rabbinate and the local religious councils, but their wage—NIS 37 ($9.63) per hour by law—is paid directly by the businesses. Beyond the built-in conflict of interest—the supervisor is employed by the supervised body—the system creates fertile ground for blackmail attempts on the part of the supervisors, who can decide how many monthly hours to put in, and as a result determining their monthly own salary. And there is nothing the business owners can do about it.

The head of the kashrut system in Hadera was recently replaced, leading to a meteoric leap in the fee some of the city’s businesses have been paying for kashrut supervision. For example, the fee of a local bakery jumped from NIS 800 ($208) to NIS 2,120 ($551.56) in one fell swoop.

The prices are increasing for no apparent reason in Netanya as well. “The supervisor comes over and makes you an offer, and then you argue with him and he settles things with you,” says Menachem Iluz, chairman of the business owners and independent workers’ association in Netanya. “It’s like a jungle.”

In Herzliya, sources in the municipality say that supervisors have come up with an original way to set their prices: “Today, the prices are determined by how close they (the business owners) are to the religious council people,” one of the council members wrote in a letter to the city comptroller about a year ago. “There are no set prices for businesses in the city.”

When there is no set price, everything goes. From conversations with business owners and a review of audit reports, it seems that in almost every city in Israel, the kashrut market is like a law unto itself. Those who refuse to pay are forced to deal with the threat that their kashrut certificate will be revoked, a move that could serve as a deadly financial blow to a business in Israel.

“They feel that they are immune and can do whatever they want,” a restaurant owner says. “They have you, and if you don’t give in to all their demands, they cause trouble for you.”

Shaming a business for complaining

The lack of uniformity is reflected in the kashrut rules as well. Two and a half years ago, ahead of Passover, a supervisor paid a visit to a veteran business in Netanya and informed the owner that after 38 years, following the arrival of a new rabbi, the procedures had changed. In order for his business to be approved as kosher for Passover, he would not be able to settle for thoroughly cleaning the oven, but would have to purchase a new oven for NIS 20,000 ($5,200). Why? Good question.

“Such a small business cannot survive this,” says the owner, who rejected the demand and publicly took on the religious council. In response, he says, the council published ads in local newspapers clarifying that his business is not kosher, and even sent over a kashrut supervisor who approached the diners and warned them that the food sold at the business was non-kosher. Having no other choice, the owner was forced to give up the Rabbinate’s kashrut certificate and turn to alternative kashrut.

The religious council is refusing to allow another business, a slaughterhouse operating outside Netanya, to sell meat to local restaurants, even though it has a kashrut certificate from other religious councils and even from Badatz Beit Yosef, which is considered strict. The slaughterhouse owner filed a complaint with the Chief Rabbinate, and its legal adviser reprimanded the city rabbi, but to no avail. More than six months have passed and the slaughterhouse owner says nothing has changed. “He is looking for all kinds of instance in which customer allegedly sent products back,” he says, “and Netanya’s residents are paying the price with the absence of fair competition.”

The local authority spokesman said in response: “The supervisors receive a fixed payment, according to the instructions of the Ministry for Religious Services’ director-general. As for the slaughterhouse, I don’t know what you’re talking about. I am unaware of anyone plotting against someone who is entitled to a kashrut certificate and is not being given one.”

In Zikhron Yaakov, a new religious council worker was amazed to discover what was going on behind the scenes in the council. She sent a letter to the Ministry for Religious Services, saying that “the religious council is being managed like a private estate, without transparency, without committees and intentionally ignoring my legitimate requests to receive information as a religious council member… Many meeting minutes are written in a distorted, false manner, which does not properly reflect the council meeting.” She also complained of nepotism and cronyism in the city’s kashrut system.

Religious council officials were unmoved by the letter. “The transparency at the Zikhron Yaakov Religious Council is a model unto others,” the council chairman responded.

So far, all the attempts to fix the violations in this area have hit a solid wall, as religious council officials have no interest in giving up their major power and the goose that lays them golden eggs, and they definitely have no interest in transparency, precisely because of testimonies like the ones published here. In such a situation, in which the supervisors are unsupervised and the religious council has no control over what is taking place on the ground, the kashrut certificate granted to businesses is likely just a frame one can hang on the wall.

That was also the conclusion reached by the comptroller of the local council of Katzrin, who was amazed to discover that the kashrut supervisors’ work in the council was basically unsupervised. “In the current situation, it’s impossible to know whether any supervision work is done and what is its nature,” he wrote. “In fact, even if there is no kashrut supervision at all across the local council, the religious council management has no way of knowing about it.”

The testimonies in the story have been verified through recordings and documents. The inevitable conclusion from these stories is that there is something very rotten in Israel’s religious services system, and that the state is turning a blind eye to the situation due to political interests. When there is a lack in transparency, each person does what he wants.

MK Azaria is planning to call an urgent discussion at the Knesset’s Economic Committee. “We knew that the kashrut area was breached, but this is apparently taking place at a very large scale,” she says. “I have asked MK Eitan Cabel, chairman of the Economic Committee, to hold a discussion on the issue. We will demand that the Chief Rabbinate and the Tax Authority conduct a comprehensive examination into the kashrut system.

“It’s unthinkable that there is an authority here which is subject to state laws but is still doing whatever it wants. Millions of shekels are being handed out in unreported 'under the table' money. They have basically created a state within a state, and we must put an end to the chaos in this area. The people of Israel want kashrut, but they won’t accept a corrupt monopoly.”

Reactions

Rabbi Shmuel Burstein offered the following response to this report: “The inspector’s visit to Hotel Yehuda was part of the regular supervision and had nothing to do with the use of a loudspeaker on Shabbat. During the visit, there was no need to search for failures ‘underground,’ because the kashrut failures were clearly found ‘on the ground.’ The meeting with Mr. Barnea was pleasant, and I am surprised by his feelings as revealed in the report. As for the terrorization claims, I would like to note that I am only responsible for the kashrut system of hotels in Jerusalem, and not for the entire kashrut system. I would like to receive a few examples of how I terrorize people while I work because, as you know, that is not my way. As for hotels’ kashrut during Passover, it is conducted several days a year and is not at the expense of the working days at the Rabbinate.”

The Jerusalem Religious Council said in response: “The kashrut supervisors are employed by the business owners. The business owners are clearly subject to the law, and so accepting a supervisor’s demand to be paid ‘under the table’ is in violation of the law. We are unaware of any complaint submitted by business owners of such a demand made by a supervisor. The Jerusalem Rabbinate has signed a contract with a manpower company, and from now on the supervisors will be employed by this company that won a Ministry for Religious Services bid. In addition, the Rabbinate requires a certain kashrut level from the businesses it supervises. Accordingly, the demands also apply to the components making up the final product that is produced and sold to the consumer. It is therefore reasonable for the Rabbinate to force business owner to purchase products from certain suppliers who have the required kashrut level.”

The Ministry for Religious Services offered the following response: “Assuming that what has been reported is true, the ministry sees such cases as extremely severe and is working on a plan to regulate the work of kashrut supervisors while severing the affiliation between them and the business owners. As for the claims regarding the religious council, the Law Against Kashrut Fraud will require all kashrut-providing rabbis to act according to the Chief Rabbinate's procedures only.”

The Chief Rabbinate offered the following response: “Different elements have decided to raise issues that have been discussed by the media in the past, in an attempt to blacken and undermine the position of the chief and local rabbinate. The issues in the kashrut area are complicated and are therefore used to attack kashrut supervisors, the vast majority of whom sacrifice themselves so that the public will receive properly kosher food.

“A special committee examining the kashrut system in Israel, which has been appointed by Chief Rabbi David Lau, is working to look into all the matters related to the kashrut-providing issue, including the desire to sever the affiliation between the supervisor and the supervised body, unified kashrut procedures, the prevention of conflicts of interest and more, in order to recommend the required amendments or changes accordingly. The issues raised in the letter are being discussed by the committee among other issues. It should be mentioned that a bill has been submitted to the Knesset to obligate religious councils to act according to unified standards set by the Chief Rabbinate.”