Trigger fingers: The IDF officers responsible for intercepting missiles

Army officers barely in their twenties are tasked with the tremendous responsibility of identifying rocket attacks on the State of Israel and launching interceptor missiles within seconds, be they Arrow, Iron Dome or Patriot. Three officers share the moments of their famous interceptions.

Lt. Dima Kisilov's first phone call, meanwhile, was to his father. "I asked him if he heard what had happened in Eilat because I was afraid he might be worried," he says, "but it turns out I had woken him up. So I told him, he was excited for a bit, and then he went back to sleep."

Before 2nd Lt. Chen Shaked could call his mother, however, she called first, but he wasn't yet at liberty to tell her what had happened. "She started asking, 'How are you? How's your Shabbat going? Is everything okay?'" he says with a smile.

"I told her, 'Mom, I'll talk to you later,' and I called back only after I got permission to tell her. She told me, 'Well done; you're protecting our country.' It was only then that I really got excited and started realizing I had done something important."

Ron, Dima and Chen are the face of a new brand of warfare. They may talk shyly, sometimes a bit too quietly, and smile with embarrassment when talking about their accomplishments, but they, along with the IDF's cyber warfare unit, are at the forefront of the battle against the threats Israel faces today.

They are the interceptors. Being a combat soldier nowadays doesn't necessarily require gun-in-hand and knife-between-the-teeth, but rather advanced technological knowhow and the courage to green-light—with only seconds to decide—the Iron Dome, Patriot or the Arrow missile-defense systems to intercept incoming projectiles. That is true for present threats and even more so for the dangers the future holds.

Each of the three is responsible for a recent, notable missile interception. The latest took place about a month ago when a missile was fired from Syria at Israel and was shot down by an Arrow interceptor. Launching that expensive anti-ballistic missile is a rare occurrence, and Chen, barely 20 years old, is the one who gave the order.

A month before that came 23-year-old Dima's big moment: A barrage of four rockets was fired from the Sinai Peninsula towards Eilat, and he was the one to give the order to intercept them using the Iron Dome.

'I was protecting my home'—Lt. Ron Shavit and a Patriot

The incident 23-year-old Lt. Ron Shavit commanded was even more unusual. It happened on July 14, 2014, on the second week of Operation Protective Edge, when tensions were at a record high.

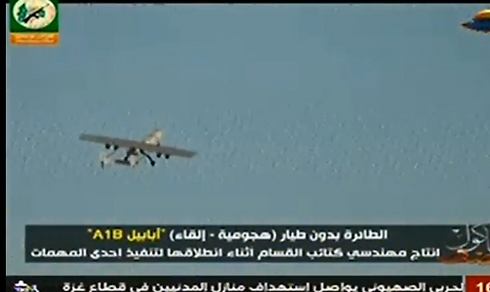

At 6:15am, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was identified coming out of Gaza and making its way towards Israel. Very quickly, it became clear this threat had to be shot down, and Ron was the one to push the button, sending a Patriot missile to successfully intercept the UAV. This was the first time since the 1991 Gulf War that Israel used a Patriot missile to intercept a threat and the first time a Patriot was used against a UAV anywhere in the world.

Ron’s entire military service has been in aerial defense. "I enlisted in the IDF as a combat soldier in 2012 and joined the Patriot unit," he shared. "Later, I became a commander and an officer and returned to the battery I started in, and now I command this battery. I really came full circle."

He was still a young officer during Protective Edge. "I finished the final stage of the officers' training course on June 30, 2014, and the war started a week later," he says. "We were presented with intelligence and told things were heating up, and the alertness level was raised. Despite that, my shift on the morning of July 14 was a routine one."

So what happened?

"I was examining the sky on the radar, and it was crowded. But all of a sudden I spotted an unfamiliar object, and I very quickly realized it was an enemy target. I immediately told the combat soldier sitting next to me, 'This one is ours.'"

That's not a trivial statement.

"Definitely not. At that point in time, our Patriot hadn't intercepted anything in 23 years."

How does the battery respond to an identification like that?

"Very quickly. The entire battery goes from zero to 100 within seconds. It's something we've drilled since basic training, throughout our specialized training as Patriot soldiers and during our officers' training course. The decision-making needs to be done very, very quickly.

"So I saw an unidentified target coming close, and I radioed the highest ranks possible—Air Force Commander Amir Eshel—and got the green light to fire. You have to understand: The time to make a decision is very short. I was only a young officer at the time, but I operated under very clear orders, so I hit the button to launch.

"All of this lasted mere seconds. Something like that can last somewhere between 10 to 45 seconds, and the decision is mine."

During that short time, did you even stop to think about the fact you were making history?

"The Patriot may not have intercepted anything in many years, but the people operating this system always believe it could happen soon. It doesn't start with the launch. We had done work ahead of time to adjust the system to the changing reality and the changing threats, and we also adjusted ourselves.

"The soldiers worked very hard so that the launcher that would eventually fire the interceptor missile would be properly maintained and to ensure it worked."

On a personal level, how did it feel to intercept?

"I live in Rishon LeZion, and I carried out the interception from the nearby Palmachim Airbase, so it felt like I was protecting my home."

'An X for every interception'—Lt. Dima Kisilov and the Iron Dome

Lt. Dima Kisilov also felt like he was protecting home. He may not live in Eilat—he's from Ma'alot-Tarshiha, far in the north of the country—but he still felt the love from that city's residents after he and his Iron Dome team intercepted a barrage of rockets fired at the resort town in February.

"Even two weeks after the interception, if (the residents) see any of us at the central bus station in uniform with the aerial defense badge, they stop to thank us," he says. "The residents also come to our battery to say hello and look around. They also bring cakes and pastries with them. We got a lot of food."

You kept the peace for them.

"Yes. My battery had only been in Eilat for seven months when we intercepted those rockets, but actually the last time an Iron Dome interception took place in Eilat was two and a half years ago, on the second week of Protective Edge, so that day came after a long period of calm."

So what happened that day?

"It was near 11pm. I was on shift as the commanding officer with another combat soldier and a technician. We also had two relatively new soldiers who joined that shift to learn and get to know the system as part of their training. Then, all of a sudden, we identified four targets."

Did you expect it?

"No. We didn't have any specific warnings—at least not anything unusual. There was no unusual intelligence concerning that particular day, and we weren't told to be on a higher alert than usual."

So how did you react?

"Within seconds, we were all on alert. It was clear to us these four targets were on their way to hit Eilat and that we only had a few seconds to make a decision whether or not to intercept them and then do so."

Doesn't the system do this work for you?

"Not really. The system is extensive; it presents a lot of data—it identifies birds and clouds as well as rockets. We need to know how to pay attention to the data, to analyze it from the system. Even if the system does identify a rocket, it's still our job to analyze the information and see if this is a threat to the citizens of Israel, or rather part of the internal fighting in Sinai.

"This is a radar-based system; there's no such thing as auto-pilot. It's all us. I remember when I was in training studying the system, I kept seeking advice and asking questions to see if I was doing okay, but I never got answers. From the start, we're taught that in real time, we have no one to consult with and that the decision-making is ours alone."

What went through your head in those seconds?

"It really is a matter of seconds; it goes by really fast. With a rocket like that, you have 15 seconds at most to decide whether or not to intercept—usually even less than that. You have to understand the full picture, but you operate based on the existing orders and your training. You're skilled enough to look at all of the data and say, within seconds, 'Okay, this isn't a bird. It's acting like a ballistic target.'

"I immediately identified that this was a barrage. I had just enough time to ask the technician what he was seeing because he was getting slightly different data than I was. The moment he too realized this was a definite threat to Eilat, I decided to intercept it. The entire thing lasted 14 seconds."

What did it feel like after the interception?

"At that moment, we didn't really register what we had done. I mean, this is something we train a lot for and hear a lot of stories about—I remember, for example, that Ron came to my base during basic training and told us about his interception—but you don't quite understand what it means to intercept, what it means to carry out an action that protects so many people. You can instantly see the result on the screen because the target simply disappears. But the deeper understanding of what had happened comes much later."

When did it really sink in?

"Only later, at about 2am, after the debriefing. It was only then that I had time to sit, alone, and really think about what we had done. It gives you a feeling of great satisfaction, and the fact that it happened on my shift was very exciting. I was a part of something very big. Because of that, just like combat soldiers mark an X on their rifles after killing an enemy, we mark an X after each interception."

'The room went quiet'—Chen Shaked and an Arrow missile

Second Lt. Chen Shaked was also a part of something extraordinary. He fired an Arrow interceptor—a missile system that is very rarely used—on March 17, and it even earned him a new nickname. "I no longer have a name; I'm addressed only as 'The Interceptor, '" he says. "They also won't let me wash the finger I used to push the button to intercept."

The Interceptor's new fame is particularly impressive considering the fact he was supposed to be an army cook. "The assignment officer at the IDF induction center told me… 'You'll be a cook or a maintenance worker,'" he remembers with a smile.

"I told him, 'No, there's no way I'm doing that. I want to be a combat soldier.' Eventually, he gave me the options of going to the Armored Corps, the Artillery Corps or aerial defense. I didn't really know what aerial defense was—just what a friend had told me beforehand—but the assignment officer started telling me about it, and it sounded interesting."

You wanted to be a combat soldier, but you chose defense over offense.

"Before the army, I was a basketball player in Be'er Yaakov. I had a coach who always told me, 'When you play offense, you're sometimes good and sometimes not. You have a good day and a bad day.

'But defense is what keeps you going. If you have a strong defense and don't allow anyone to get past you, you'll be more confident in your offense.' It's the same in aerial defense—the importance of defense serves us in our offense as well during war time."

And how did you get to the Arrow unit?

"I was a combat soldier in the Patriot unit under Ron's command. From there, I went on to the officers' training course, and, during the final stage of training, I decided I wanted to switch to the Arrow system. I had all kinds of commanders who told me about the system and got me interested in it, and I wanted to be involved in something that was so important to the State of Israel."

How long were you at the Arrow battery before the interception?

"A month and a half."

And what happened during that shift?

"It was during the night between Thursday and Friday. I started my shift at 2am—a regular shift. I got a rundown, and everything was going as it should. There was no intelligence warning; there was nothing special. Then, all of a sudden, a target moving towards Israel appeared on the screen."

That must have been stressful.

"We train for this a lot, so I knew what I had to do, despite being young. I had drilled this, and I know that when I make a decision—in accordance with orders, of course—I'll have full backing.

"In this case, I simply identified a ballistic threat to the State of Israel, and we immediately called in the team we needed for interception. It was very quick. Fourteen seconds after we called the team in, everyone was ready to intercept when given the order. Then I made the decision to do it."

Did you have no one to consult with?

"No. It was just me, on my own, against the missile. In my system, the window of time for making a decision is very small, and you have no one to talk to. By the time I take this upstairs, the missile could hit. There's not much you can do about it besides knowing it's down to you. And then you make a decision based on the orders."

So you pressed the button.

"Yes. And a second or two later, my commander happened to enter the room. I pointed to the board and told him, 'Look, Arrow has been launched.' I was told I stuttered, but I don't remember that. I do remember that he looked at me and said, 'Well done.'"

In those initial moments, before the debriefing and investigation, and before the army officially determined the interception was justified, did you think that perhaps you didn't act correctly?

"I knew that I had done the right thing. My target identification was very clear. But there was this feeling of uncertainty."

And how did others react? After all, an Arrow interception is rare.

"In the first few seconds, the room went quiet. I don't know why; it just went silent. You expect that when something like this happens, that there would be noise, shouting. The Arrow was launched, that's not something that happens every day. But it was quiet. Only a little while later, we started smiling and told each other, 'Way to go!' and 'You’re the man!' There wasn't a deep conversation about it."

Did it take you a while to really understand what had happened?

"Yes, I couldn't fall asleep. The interception was at 2:40am, and at 4pm, I finally went to bed, but those seconds kept playing in my head, and I couldn't calm down. At 5pm, I realized there was no chance I was going to fall asleep, and I got up. I only managed to fall asleep at midnight."

You also had to do a debriefing.

"Yes, I had to stand in front of all the soldiers in the battery and explain what I had done. I also heard the criticism from outside, like from Ehud Barak, about the fact the interception wasn't necessary. But I don't let that get to me; I only listen to my commanders."

And what's happened since?

"This kind of interception is something that stays with you. A week after that, we went on a large-scale training exercise, the kind we do every four months, and the reserve soldiers started asking around about the interception. I happened to be there, and they told me, 'It's you? You kid, we've been waiting for 20 years to do this, and you got to?'"

From planning to operational—Zvika Haimovich oversees his officers

Brig. Gen. Zvika Haimovich listens to the three officers tell their stories with a proud smile on his face. He's been heading the IAF's aerial defense network for a year and a half now after having had many years of experience with Patriot, Iron Dome and Arrow.

Today, Israel is the only nation in the world to have a multi-layered defense system against ballistic missiles comprised of the Iron Dome, David's Sling and the Arrow systems. This is mostly because Israel is also the only nation in the world to be under a constant threat of ballistic fire at any given moment and on several fronts.

"We're just marking six years to Iron Dome's first operational interception," Haimovich says. "It was on April 7, 2011, on a Thursday—only five weeks after the system was delivered to the Air Force and only four days after it first became operational.

"We just had an inauguration ceremony for David's Sling, and it's important to understand that this isn't just a ceremony. If, a minute later, a ballistic threat had presented itself, David's Sling could have intercepted it.

"To us that seems very natural sometimes. We host officials from abroad, and I explain to them that just over the past decade, over 12,000 direct threats have been fired at the State of Israel from the Second Lebanon War to all of the rounds of fighting in Gaza since.

"There's a changing reality, and we need an aerial defense apparatus that adjusts itself to it and builds itself up. That's how the idea of four layers of defense—Iron Dome, David's Sling, Arrow 2 and Arrow 3—went from a PowerPoint presentation to an operational system in less than a decade."

But will all of this be enough in the next war?

"We keep watching Hamas, and it's obvious to us that just like we have been learning a lot since Protective Edge, so have they. We're in a race—they realize that Israel's aerial defense is what prevents them from fulfilling their full potential of causing damage, and they'll try to do whatever it takes to get past our systems and challenge them."

During the 2006 Second Lebanon War, there was a ratio of one dead for every 90 rockets fired at us. During the 2008 Operation Cast Lead, there was one dead for every 110 rockets. During the 2012 Operation Pillar of Defense, we had one dead for every 250 rockets, while during the 2014 Operation Protective Edge, it was one dead for every 750 rockets. Looking at these data, what would a future Lebanon war look like?

"It would have more of everything. We'll see more extensive rocket fire, with bigger barrages covering a wider area. If during Protective Edge, 70 percent of the population was under threat for 51 days, then in a future war in Lebanon, a bigger area of the country would be at risk."

During Protective Edge, you had a 90-percent success rate with Iron Dome. This wouldn't happen in an all-out war.

"And that is why I'm most concerned about this feeling of security. Here's a story: One Shabbat during Protective Edge, I visited an Iron Dome position near Ashkelon. When I drove into the city, I saw a religious family—father, mother and three children—strolling on the street.

I asked them why they were wandering around there, only an hour after…a rocket had fallen. They told me, 'It's okay, we have kippot.'" (In Hebrew, the word "kippa" means both "dome" and the traditional Jewish skullcap.)

"I told the father, 'In this case, the kippa on your head won't help you. It's irresponsible; you should go to a shelter.' So he replied, 'No, I have these kippot,' and he pointed at the Iron Dome battery.

"To me, that's the biggest danger. This feeling of security among the public can lead to complacency. The public needs to understand this protection is not foolproof."

What does it mean for a future conflict?

"It means rockets will fall in the next war against Hezbollah, and the challenge will be to minimize these rocket hits and manage them. We won't be able to protect everything. There will be places we'll define as high priority—densely populated urban areas or important assets—while in other areas, more open and less densely populated, the priority will be lower."

(Translated and edited by Yaara Shalom)