Small stories from the big city

Ynetnews invites you to a tour in our time machine, and this time: Three bits of nostalgia from Tel Aviv’s history

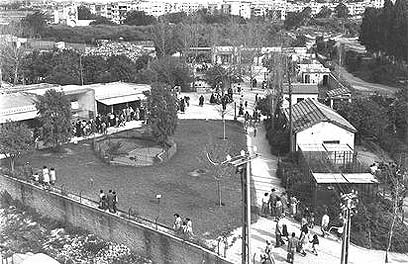

Garden of Eden

There are facts you’ll still marvel at no matter how many times you hear them, facts that will be hard to imagine. Was there, once upon a time, a zoo in central Tel Aviv? In the middle of Ibn Gvirol Street? The answer is yes.

As in most stories and legends, the story of the zoo begins with the dream of one man, Rabbi Moshe Shorenstein. In 1936 he decided to come to live in the Land of Israel - a wise decision, considering world events - and on his way there he spent some time in Italy, where he bought a few birds and animals, including a small monkey, with the aim of making them into an attraction for the children of Tel Aviv.

Shorenstein housed his gang of new immigrant animals in a small store he opened on Shenkin Street, called “Zoo.” As the years went by, the animals multiplied, as is their wont, until the store became too small to contain them all.

Fortunately, Shorenstein found temporary salvation when his friend Shlomo Yaffe provided him with a slightly larger apartment on Hayarkon Street. But this didn’t last long because the neighbors complained about their unexpected proximity to the animal kingdom.

Tel Aviv's zoo (Photo: GPO)

Then a small bear’s escape to the streets of Tel Aviv became just too much, and city leaders decided by majority vote that a more appropriate solution would have to be found. As was the custom at that time, a committee of public figures was formed to find a solution.

Committee members toiled and toiled until they found a large, fairly isolated area. Now all that remained was to find the money to purchase the land. According to the rumor, Justice Bechor Shitreet, a member of the committee, went on a fundraising journey among the cafes of Tel Aviv until he raised the required 1,200 Israeli pounds.

At the same time Tel Aviv’s mayor, Yisrael Rokeah, went to work overseas for the glory of the Tel Aviv zoo, and succeeded in obtaining a pair of lion cubs from the Egyptian government, as well as tigers and bears contributed by a generous Indian Jew.

Within a short time the work was completed, and in 1938 Tel Aviv got a real zoo that quickly became a popular destination for the city’s children (and even brought in revenues of 800,000 pounds in its first year).

In subsequent years the Tel Aviv zoo continued to expand, receiving a variety of animals from all over the world: Animals and fowl from farms, several swans donated by British army officers, a Persian bear donated by Polish soldiers, a tiger from the Galilee, Dolly the lioness, who was brought from another zoo after being exhibited on a truck on the streets of Tel Aviv, and others.

The zoo had a number of crises, such as a bold attempt by lion cubs to escape from their cage, causing two women visiting the zoo to faint, or the young chimpanzee’s escape to the nearby photography store.

National crises also affected life at the zoo, and Yedioth Ahronoth revealed during the Yom Kippur War that the elephants, the rhinoceroses, and the monkeys were suffering from the many air raid sirens (the flamingos, on the other hand, multiplied greatly during the war). During the war, a special police unit stationed in the zoo was ordered to shoot wild animals to death if the zoo was bombed by the enemy.

In the legends it was customary to end with “and the animals of the world and the people of Tel Aviv lived happily ever after.” But reality, by its nature, tends to be somewhat more bitter.

As the years went by and the city developed, the previously isolated area was surrounded by buildings, and people lived in the buildings, and they weren’t enthusiastic about their animal neighbors, to put it mildly. Rumor has it that the zoo’s residents also began to suffer from the urban overcrowding.

City officials had no choice but to seek advice once again and ultimately decided that central Tel Aviv could not be a miniature jungle, that the zoological enterprise would have to come to an end, and that the animals would have to be moved to the Ramat Gan safari.

In 1980 the animals were moved to their new home. In honor of this happy-sad event Yitzhak Steinberg, a long-time worker at the zoo, was interviewed by a newspaper:

“Tel Aviv’s zoo is an incomparably fascinating slice of life. I went to the directors and asked them to take me to work in the safari. I have a connection with animals; I can’t leave them just like that. They told me I wasn’t needed. They’ve gotten what they want from me, and I can go. But for me it isn’t over. I’ll keep going to the safari.”

From here on in the story is well known: The zoo was replaced by the Gan Ha’ir shopping mall and a park, which was a boon to aficionados of designer fashion and luxury apartments and saddened the children of Tel Aviv. And the animals? For some reason the paper didn’t report on them, but we can guess that the animals, like some of Tel Aviv’s young people who grew up, loathed the urban tumult and settled comfortably into their suburban environment.

The vision of the end of days

On August 16, 1959, Yedioth Ahronoth reported something astonishing: People were swimming in Tel Aviv. This in and of itself is not especially surprising, unless you realize that they were swimming not in the sea, but in the waters of the Yarkon River. And they weren’t just swimming; they even dared to dive to the floor of the river.

To clarify what was known to every resident of Tel Aviv at the time, the reporter writes that the pumping of the Yarkon’s waters in the early 1950s and the flow of sewage water into the riverbed turned the river from a natural pearl into a source of disease-carrying germs, bad smells, and other disgusting things.

This is how spending time near the river, not to mention swimming in it, became a dangerous and dubious experience that no intelligent person would agree to of his own free will.

Then, two weeks before the swimming incident, a new sewage collection plant was opened and the sewage water was made to flow into the ocean (perhaps in order to deter those who swam in it). At the same time the differences in height caused the ocean water to flow into the river channel. The salty ocean water immediately killed the germs and other dangerous organisms and returned the river water to its former glory.

The residents of Tel Aviv, being naturally adaptable, quickly took to this welcome change, not only swimming in the river, but even fishing in it.

The reporter quotes one of the old-timers who nearly shed a tear over the revival of the river: “If anyone had told me a month ago that the Yarkon would be cleaned up I would have looked at him as if he were crazy. Today I believe that the miracle we all prayed for has occurred.”

Equality before the law

Newspaper headlines show us that even Israeli prime ministers were occasionally asked to put their house in order. It sometimes seems like this is something new in Israeli politics that the founding fathers were not in the habit of bothering themselves with such trifles.

As in so many other cases, the fog of nostalgia makes it hard to make a definite determination, and since we can’t tell either, we’ll have to make do with recounting a little anecdote.

Yedioth Ahronoth reported on its front page in May 1950 that Israeli citizen David Ben Gurion (profession: prime minister), the owner of a home at 17 JNF Boulevard, asked Tel Aviv authorities to reassess how much he was paying in city taxes. The request was prompted by the city’s demand that Ben Gurion pay additional taxes (to the tune of a whole seven pounds) after he added a room to his house.

What reason Ben Gurion gave for his request, whether he asked city officials for the discount or requested the special discount for the country’s founding fathers, we cannot know.

The house on JNF Street (Photo: Chen Mika)

In any event Yedioth, loyal to the dictates of investigative reporting, noted not long afterwards that the city appeals committee rejected the prime minister’s request and determined that he must pay his taxes as required. The journalist asked people for their responses to this sensational news from Tel Aviv.

One of the respondents, a storeowner, stated that he believed the prime minister’s attempt to lower his taxes was mistaken:

“Things should not have come to such a pass. The prime minister may not make mistakes. He needs to know in advance whether or not his appeal has a basis… because the prime minister needs to think carefully before he begins to act. Let’s suppose that he decides that we must go to war, and afterwards it turns out, God forbid, that the conditions for such a move are lacking because the prime minister did not carefully check what he should have checked before he decided… In my opinion, this must not happen.”

“You shouldn't exaggerate, sir,” said the journalist. “After all, it’s only seven pounds.” The storeowner replied: “The amount doesn’t matter. The same thing applies to small sums as to large sums. The principle, sir, is worth more than the money.”

Do you have more details? Write to [email protected]