Remnants of the intifada

Exiled Palestinian leader recounts 2002 siege on Bethlehem church, calls it 'victory over IDF'

"A day or two before the deportation, the numbers Israel was really planning on exiling came in, and we were shocked. We knew all the time about just seven, and here we hear that that they are going to deport 39 – 13 to Europe and 26 to Gaza.

"They told us we would be exiled until our records could be discussed. We never thought it would take this long – it's been nearly nine years."

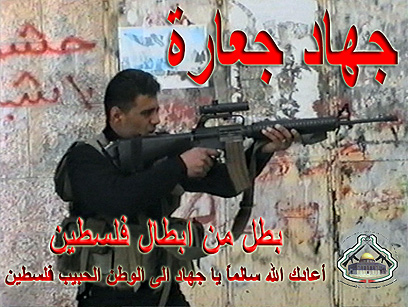

Jihad Jaara, born in al-Aroub refugee camp near Bethlehem, became known during the siege on the city's Church of the Nativity in 2002. Then the leader of the Fatah's military wing, the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigade, he had led the fighting against Israel in the West Bank.

Jaara was wounded in Bethlehem's Old City, in the final showdown with IDF soldiers before he and other gunmen enclosed themselves in the church for a last stand that lasted 39 days, until May 10, 2002.

"The psychological battle was the hardest part of that time," Jaara told Ynet from his home in Ireland, which accepted him as an exile. "The Israeli army didn't let us rest. There was firing into the church, and many injured and eight dead. The first two of them stayed in the church for 20 days. They brought the mothers of the people inside in order to influence the sons. We lacked food, and there were other difficulties."

Despite all this, he says, "We did not give in or turn ourselves in, and we only came out after they promised us European and American supervision of the deal."

Jaara also rejected reports made public at the time, saying the men picked on church personnel, looted and injured them. "This was IDF propaganda," he said. "How could we have had nothing on us when we emerged? They searched us from head to toe."

On the contrary, he said, "The priests and nuns took care of us wonderfully, and not as though they were forced to do so. The treatment we received in the church is unforgettable. You can ask the sick nun who refused to leave the church because she feared for our wellbeing, and wanted to identify with us."

The exiled leader added that the church was a last resort for many. "The last battle before we sought refuge in the Old City was very difficult – intense fire, four choppers over our heads, dozens of tanks and forces surrounding us. The church seemed like the safest place," he said.

Jaara. 'Not a terrorist'

'Ireland just one big prison'

On May 10, after 39 days in the church and following a quick interrogation by Gush Etzion Police, 26 of the men were deported to Gaza and the rest were flown to Cyprus, from whence they left for various European countries.

Jaara is far from satisfied with this solution. In Ireland, he says, he is just "in one big prison". He is prohibited from leaving the country, and has very limited freedom. Every morning he listens to news broadcasts from the Palestinian territories, followed by some sports. Then he may meet with friends he's made, or give a lecture at the university or a pro-Palestinian organization.

But the IDF claims Jaara has been involved in planning attacks, even from his Ireland home. Officials claim he has been working with Kais Obeid, the Israeli-Arab turned Hezbollah leader who captured Elhanan Tannenbaum in Lebanon. But when Jaara is asked about this he retorts, "That's what they say."

Jaara became a wanted man on the first day of the 2000 intifada, when he was involved in the first armed clash in Jericho. He was serving there as a trainer of armed militia men.

But the IDF was already familiar with the name Jihad Jaara. He had spent his 13th birthday in an Israeli prison for throwing firebombs and stones at army vehicles in the refugee camp in which he had been born.

Jaara completed high school in a special school in Hebron, after which he studied education and psychology at UNWRA's college in Ramallah. During his studies he served as a Fatah operative and was eventually promoted to chief of security at the Orient House in Jerusalem, a duty he performed until 1997, when he joined the security forces' training department in Jericho.

In the meantime he married and had four children. The first two, Udei and Kusei, also carry the name Saddam Hussein, as a symbol of Jaara's esteem for the former Iraqi dictator.

Jaara in 2002. 'Not easy being a wanted man'

How Israel created al-Aqsa Brigades

Jaara, who is accused by Israel of involvement and planning of terror attacks, recalls how two months after the intifada began, Fatah decided to organize into one unit various operatives who were already carrying out attacks individually.

"The failure of negotiations at Camp David and the following Israeli suppression of non-violent protests in the first days of the intifada, as well as the lack of any political light at the end of the tunnel, led to the establishment of the brigades," he recounted. The result was the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigade, made up mainly of trained Fatah security personnel.

Jaara refused to comment on the sources of funding, policy, and orders for the first attacks. "These are secure details I cannot reveal," he says.

In those days, Jaara evaded the IDF as he moved from Jericho to Ramallah, and from there to Bethlehem. "I wanted to be close to my family in al-Aroub," he explained. It was not easy being a wanted man, he said, "But we were fortunate because the population supported us and strengthened us, and this helped us fight."

"It was not a fight to kill Israelis, but a battle to win our freedom," he says. Jaara is upset that the word "battle" has become synonymous with terror in Israeli minds, and does not define himself as a terrorist.

"I do not plan to argue about this," he says. "But if the Israelis define me as a terrorist because I fought against the occupation and for our release, then I am proud to be a terrorist. We have never believed in killing for killing's sake."

'I prefer checkpoints to Europe'

The brigades and the cohorts attacked severely during the first year of the intifada, until Israel responded with Operation Defensive Shield. "There were tough battles, and the Israelis kept sending in more forces. We withdrew, I was injured, and then we made the decision to enter the church," Jaara recounted.

There were hundreds already inside, he said – scared civilians, regular security personnel, armed men, and even the mayor of Bethlehem. "There was stress, there was pressure, there was even yelling now and again, but there was no fighting. Just the opposite, there was a great understanding between us. We agreed on a schedule and discipline, and orders of movement inside the church," Jaara said.

But the lack of food, Israeli pressure, and nerves finally convinced the leaders of the group to come out. "It was our victory over the Israelis, over their power and technology. Our stance was not trivial. This is why, in order to take revenge on us, the Israelis upped the number of people to be deported from seven to 39," he said.

And finally, Jaara claims to have no regrets for all he did during the intifada. "I only sacrificed the minimum for Palestine and the hope that our children will live in their own independent state," he says.

But in the meantime, he dreams of the West Bank. "I prefer the checkpoints in and the sewers of my refugee camp to the paradise of Europe," he says.

Still, Jaara knows his dream is far from becoming a reality. "I don't believe in negotiations. Just the opposite – I see Israeli bullheadedness in the matter of settlements and other issues, and it seems pretty similar to the time before the intifada, when the failure of the talks led to an uprising. We are probably headed towards a similar stage. It's only a question of when."

- Follow Ynetnews on Facebook