'Sometimes being called traitor is a badge of honor'

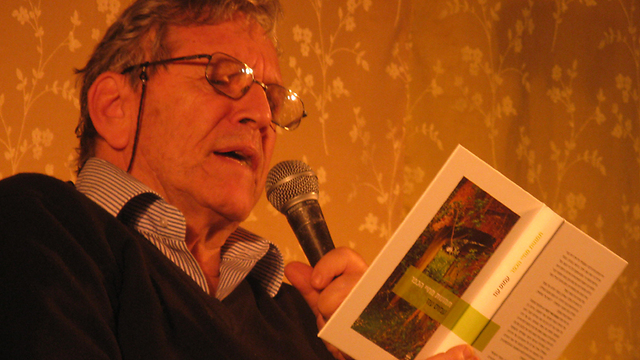

Amos Oz discusses his new book about Judas Iscariot, the fulfillment of the Zionist dream, and the danger of extremism.

When the editor of the newspaper called and asked if I'd be willing to interview Amos Oz to mark the launch of his new book, I agreed immediately. I was one of Amos' students. I owe him a big thank you for the numerous gifts of wisdom and beauty he bestowed upon me in his classes and books. And I thought this would be a good way to repay him, and an excuse to meet with him, one on one, after not having seen each other for quite some time. You need to understand: Writers are islands unto themselves; they're all engrossed in their craft, and one rarely gets the opportunity to sit down for a proper talk with them.

Oz's new and fascinating novel, The Gospel According to Judas, also begins with an invitation to converse. Shmuel Eish, a student who drops out of school following a failed love affair and is just about to leave Jerusalem, comes across a notice outside the cafeteria that is offering free board and a modest monthly wage to someone who'd agree to serve as company for a 70-year-old disabled man who "needs conversation primarily and not nursing."

At the small and dingy home of the disabled man, Gershom Wald, Shmuel Eish will also meet the captivating and devious Ataliah; and with both, he will engage in fascinating conversations about love, betrayal and loneliness, as well as a specific point along the axis of time at which Zionism could ostensibly have chosen a different path – and didn't.

Oz and I sit down to talk in his study, late in the morning, surrounded by numerous books, drinking tea and chatting, just like the characters in the book.

Your new novel is filled with conversations. Reading it made me think that we live today in a world in which heart-to-heart talks are few and far between. Do you still find the time to talk to people?

"Yes, but more so to people of my generation than to young people. I manage to speak with students; that I do – not in the lecture halls, but in my office, before or after class. But you're right, people talk less and tend to send text messages or leave messages instead.

"In the book, one the other hand, you have three people who are closed up for an entire winter, a cold and rainy Jerusalem winter, in a small stone house. What else could they do but talk? Moreover, one of them is getting paid to talk and another is paying to be spoken to."

On traitors and betrayals

Do you remember when you started thinking about this book? I know I sometimes invent the stories of the birth of my books in retrospect because I'm unable to pinpoint the precise moment of conception.

"It's really difficult to answer that. In a way, I've been thinking about this book all my life. The question of what is it traitor has occupied my mind since a very young age – also because already as a child, I was branded a traitor."

What could you have done?

"I was seen associating with a British sergeant. Ours was a neighborhood of underground members – pro-Irgun, pro-Lehi pro; my house was no different. And I dared to associate with a British sergeant, so they called me a traitor. And there's also the story of Judas Iscariot. The name, Yehuda, is an integral part of my life. My father's name was Yehuda Aryeh. My son, Daniel Yehuda Aryeh, is named after him. Yehuda is a common, everyday Jewish name, with positive connotations; but in other languages, if you call a person Judas, you may as well spit in his face. In the Christian tongue, Judas is the epitome of betrayal and humiliation and the embodiment of the relationship between Jews and betrayal and lowliness. I have carried this with me for many, many years – long before I even knew I'd write a book."

Do you have a fondness for traitors? Do you feel empathy, solidarity with them?

"I'm attracted to a certain type of traitor – not the run-of-the-mill traitor who receives money and passes on information in return. I'm interested in the individual who is viewed by those around him as a traitor, but in actual fact, in his heart, he is sometimes the most loyal, most devoted and most loving of all. There's a moment in the book when Shmuel says that a traitor is sometimes – not always, but sometimes – someone who changes in the eyes of those who don't change, someone who changes in the eyes of those who hate change and don't understand change, and are afraid of change."

Before coming here, I Googled the phrase, "Amos Oz traitor", and I'm sure it won't surprise you to learn that my search yielded results. When you sent a copy of A Tale of Love and Darkness to imprisoned Palestinian leader Marwan Barghouti, for example, you were accused of treason.

"Actually, I've been called a traitor since '67, because ever since '67, I have supported a two-state solution. At the time, by the way, there were so few who advocated this solution that we could have held a national convention in a public telephone booth. I may have been the first to write that the occupation would deprave us. So yes, I've been called a traitor – I always have been. And it came back with a vengeance this past summer. But I wasn't the only one branded a traitor last summer. Who wasn't branded a traitor?

"Sometimes – not always, but sometimes – the title, traitor, can be worn as a badge of honor. If we look back for a moment, many of the greatest leaders of the 20th century were branded traitors by some of their people – Churchill, when he broke up the British Empire; de Gaulle, when he took pulled France out of North Africa; Ben-Gurion, when he agreed to the Partition Plan; Begin, when he evacuated the entire Sinai; Sadat, when he came to Jerusalem; Rabin, when he signed the Oslo Accords; Sharon, when he withdrew from Gaza; Gorbachev, when he dismantled the Soviet Empire. Traitor is sometimes a title of respect.

"A traitor is sometimes someone who dares to change. The day they start calling Netanyahu a traitor will be the day I know that something may be in the works."

And do you think there's any chance of that? He appears less and less capable of change as time goes by.

"Let me tell you something – and not necessarily about Netanyahu in particular. Human nature is open, not closed. There's a small cat here that's been sleeping all this time; perhaps you haven't noticed. He's not going to change. He's going to be the same cat all the time. People can. People are capable of surprising others and even themselves. You're still capable of surprising yourself. Even I, who am older, may still be capable of surprising myself. And we've already done so once or twice in our lives. I'm not asking you, but I'm sure you've surprised yourself once or twice in your life.

"I don't know if Netanyahu will be the one; but I will say that the person who will pull Israel out of the territories and do what everyone knows deep in their hearts needs to be done already walks among us. Who is it? I don't know. Perhaps he or she doesn't even know yet."

The kiss

Let's speak for a moment about the most notorious traitor in the history of mankind, Judas Iscariot. You're actually doing something very subversive in this book; you're retelling his story in a manner that undermines a Christian narrative that has defined the relationship between Christians and Jews for thousands of years. I wonder how your many readers abroad will feel about this. How will they feel about a Jew rewriting their history?

"I have a letter sent to me by my Italian editor, a non-religious Christian. His reaction to the book was one of astonishment – no less. After all, the story about Judas Iscariot is a fundamental story in the Christian world. Millions of Christian children grow up in a room on the wall of which hangs a man with nails in his hands and feet. Even if you subsequently become a Marxist, the question of who killed the Lord doesn't leave you."

And how did you end up dealing with this explosive topic?

"The enigma of Judas Iscariot has accompanied me from a very early age, and I have searched for an answer to it. Many years ago, I went and checked, for example, how much is 30 pieces of silver. That, after all, is what they allegedly paid Judas for his betrayal. But 30 pieces of silver at that time was the cost of an average slave – hardly sufficient temptation for a man who is said to have been well off and comfortable. Why all of a sudden would he sell out his teacher and mentor for 30 pieces of silver?

"And let's assume he did. That same night, he goes and hangs himself? A person who has just sold out his master for 30 pieces of silver goes and hangs himself? It didn't add up to me.

"And something else didn't add up either – the most famous kiss in history, the kiss of the traitor, Judas Iscariot's kiss. When they came to arrest Jesus, why did he have to kiss him for the detainers to know it was him? First of all, Jesus never denied being Jesus. Secondly, all of Jerusalem already knew what Jesus looked like. He wandered the city. He overturned tables. He was known.

"The whole story didn't add up to me. It bothered me for years – also due to the fact that Judas is the Chernobyl of anti-Semitism. This book emerged from the pit of my Jewish stomach for all haters of Israel, for all those who cried Judas and drove the dagger into us or burned down the synagogue with the Jews alive inside it."

At a certain point in the book, Gershom Wald says that our problem, the Jews' problem, is with Christianity and not Islam, that our score with the Christians has yet to be settled. Do you really think so – even after this past summer and in light of what is happening with Islamic State in Syria and Iraq?

"I think the problem facing the world is fundamentalism. The curse of the 21st century is fundamentalism of all kinds – and Muslim fundamentalism first and foremost; but Jewish-Israeli fundamentalism too, and also Christian fundamentalism in America's deep south; or in Russia; and anti-Semitic fundamentalism too; and the fundamentalism of the violent radical left; even some of the environmental groups are fundamentalists. This is the problem of the 21st century."

A kid with nothing to lose

Your public voice was quiet this past summer.

"I didn't write articles this summer because I was in hospital. I'll tell you something, aggression must sometimes be stopped by force. That's where my path veers off from the path of the European pacifists. My father-in-law, Prof. Eli Salzburger, had a mother who spent the war in Theresienstadt and survived. And she told me more than once to remember that those who liberated us from Theresienstadt and the Nazis weren't peace demonstrators with placards and olive branches but soldiers with helmets and submachine guns. I never forget that.

"The second thing I learned this summer was that if we had any sense, we would have long since accepted the solution that deep down in our hearts almost all of us know is the solution – and everyone knows what it is too. If there was a free Palestinian state in the West Bank, without checkpoints, without humiliation, without price-tag incidents, without settlers who destroy crops, and if independence and prosperity reigned in Ramallah and Nablus, Gaza would do to Hamas what the Romanians did to Ceausescu because it would want the same. This would have been the way to prevent the war. That's what we failed to do. It's our sin. When it broke out, of course we had to lift a stick to defend ourselves. But war with Hamas is a lose-lose game. If they kill Israelis, it's great for them. If we kill Arabs, it's great for them too."

"When it comes to Gaza, let me tell you something simple. My grandmother used to say to me when I was a child: 'Amos, never fight with a kid who has nothing to lose.' Gaza is a kid who has nothing to lose. It is in our existential interest to ensure that Gaza has something to lose, just like Ramallah has a little to lose – a little, fortunately for us; otherwise Ramallah, too, would be a Gaza."

Do you think Israel should talk to Hamas?

"Israel has been talking with Hamas for many years. But peace with Hamas is possible only if Hamas rejects its call for the destruction of Israel. I am a man of compromise, but even a man of compromise like me cannot offer Hamas a compromise when it comes to the destruction of Israel – like, for example, that Israel will exist on Mondays, Wednesday and Fridays only."

And what of the left's classical solution, two states for two peoples? Is it still relevant under the current circumstances?

"Apart from Switzerland, there are hardly any multinational states left in the world – and certainly not in our neck of the woods. Almost all ended up entangled in a bloodbath – Cyprus, Lebanon, Yugoslavia, Ukraine, Syria, Iraq. After 100 years of hatred and violence, there's no chance and no point in trying to lay the Israelis and Palestinian down together in a double bed and expect a honeymoon. If there aren't two countries here, and quickly so, there will be just one country here. If there is one country, it will be an Arab country. And if there's an Arab country here, I don't envy our children and grandchildren."

Let me ask you a question I sometimes ask my parents, who are of your generation. Is this the country you imagined, dreamed would be established here?

"Israel was born out of a dream, or an entire spectrum of dreams. Every dream that is fulfilled leaves behind a taste of partial disappointment. The only way to maintain the purity of a dream is not to fulfill it. This holds true when it comes to building a house, writing a novel, traveling the world or fulfilling a sexual fantasy. Israel is a dream fulfilled, and thus necessarily leaves behind a slight taste of disappointment, despite the fact that it is still a fascinating fulfillment of some of the dreams.

"The disappointment stems not only from Israel's image. The disappointment lies in the nature of every dream that is fulfilled."