Why Boehner's invite to Netanyahu is unconstitutional

Op-ed: Boehner's decision not to consult Obama contradicts constitutional stipulation that it is the president who should receive foreign dignitatries.

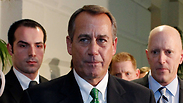

(Reuters) - House Speaker John Boehner's annoyance with President Barack Obama is turning into a grudge match against the Constitution.

Boehner's decision to invite a foreign head of government to address Congress without first consulting the sitting president has no precedent in American history. And for a simple reason. It's unconstitutional.

Boehner (R-Ohio) fully admits that his failure to communicate with the White House was not an oversight. Like a schoolboy passing notes when the teacher turns to the blackboard, he sneaked behind Obama's back to set the date for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's speech with his country's ambassador to the United States. Boehner asked the foreign dignitary not to tell the US president.

"I wanted to make sure," Boehner later explained on Fox News, "there was no interference." Netanyahu is now scheduled to address a joint session of Congress on March 3.

This is unheard of in US history. American Congresses have sometimes rejected a president's foreign policy, of course. That is within their rights.

Though the president has the power to negotiate agreements with foreign countries, the Senate can reject or approve them. President Woodrow Wilson, for example, journeyed to Paris in 1919 to negotiate the Treaty of Versailles after World War One. Wilson was instrumental in writing the treaty, particularly those sections that created a new institution, the League of Nations, to provide collective security.

When Wilson returned home, he conducted a whistle-stop campaign across the country to build support for the new league. But to no avail. The Senate was under the sway of isolationists. One influential senator, Henry Cabot Lodge, disliked Wilson personally. Wilson had also alienated the upper chamber because he took no senators with him to the peace talks. The Senate voted to reject the treaty. Its decision not to join the League of Nations may have been a mistake - but this was the Senate's prerogative.

There is one key job, however, that the founding fathers assigned to the president alone. The Constitution says that the president "shall receive ambassadors and other public ministers" from foreign governments.

Why did the founders do that? According to Stanford University professor Jack Rakove, who won the Pulitzer Prize for his book on the subject, they entrusted that responsibility to the president for a specific reason: to facilitate bilateral negotiations on complicated matters on behalf of the United States.

Congress has the authority to declare war. The House and Senate hold the purse strings and represent the will of the entire nation. War is also a public, unilateral decision. It required only a "simple and overt declaration," James Madison wrote in the notes he took at the Constitutional Convention.

In contrast, the president is charged with making peace - and "peace attended with intricate and secret negotiations." So the founders placed the president in charge of meeting with foreign ministers on delicate matters requiring discretion.

The founding fathers would be horrified by Boehner's current actions. They had a passion for checks and balances. Madison, the father of the Constitution, distrusted power in the hands of mortal men. He feared both mob and monarchical rule.

So Madison and the founders - George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin and the other 51 delegates who met at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 - intentionally divided the federal government into three branches. The executive, legislature and judiciary each had its own powers and duties. In a few clearly defined situations, one branch could veto another's decision.

The men who met in Philadelphia over that muggy summer of 1787 were anticipating situations precisely like the one now at hand.

Obama is attempting to negotiate an end to the Iranian nuclear crisis. The United States is cooperating across the board with other world powers in this volatile, dangerous situation because nuclear escalation potentially affects every nation on the planet. The United States, Britain, China, Russia, Germany and France all have negotiators at the talks trying to keep the peace and persuade Iran to stand down.

Boehner disapproves. Or at least he wants Congress and the American public to hear Netanyahu's advice on the matter at a formal meeting in the US Capitol. Yet inviting the Israeli prime minister is an express - and entirely novel - breach of the Constitution.

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson was first to reprimand a foreign dignitary for appealing to Congress over the head of the executive. When Edmond-Charles Genet, who represented the revolutionary government of France, sought congressional support in 1793 for a policy opposed by President Washington, Jefferson brought him up short. Even though Jefferson himself had great sympathy for France's viewpoint.

The president, Jefferson wrote, "must be left to judge for himself what matters his duty . . . may require him to propose to the deliberations of Congress." Or, as Washington said on another occasion, the Constitution designated him the "sole channel of official intercourse" with foreign nations.

What's the harm in setting a new precedent? History shows that the commander in chief has sometimes overstepped his bounds - or at least stretched them.

At the outbreak of World War Two in Europe, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive agreement with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to trade US naval destroyers for bases in the British West Indies. Newspaper editorialists labeled FDR "Dictator Roosevelt."

In this situation and others, members of Congress sometimes complained that the president had exceeded his mandate as commander. Similar concerns during the Vietnam War led Congress to push back. It approved the War Powers Act of 1973 to rein in executive authority and reaffirm its own.

Our founders foresaw that the division of power invited competition. All sides would bump against the rules. So why shouldn't Congress just do what it feels like? Take a flyer?

Improvising on the Constitution is not a smart idea. Boehner should rescind his invitation, or Netanyahu should RSVP his regrets, because willful law breaking chips away at America's most precious possession, the true bulwark of our liberties.

This wise, sacrosanct document, the Constitution, is the one thing on which all political parties have agreed for more than 225 years.

Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman is the author of "American Umpire." She is the Dwight E. Stanford chairwoman in U.S. foreign relations at San Diego State University. The opinions expressed here are her own.