Putting Jerusalem on the map: Ancient drawings of the holy city

From a monk’s simple and enchanting illustration, through the French diplomat who omitted all Muslim sites from his ‘accurate’ map, to the Spanish Jesuit scholar who sketched elements that were archaeologically confirmed later on: Dr. Milka Levy-Rubin of the National Library of Israel explores Jerusalem’s different transformations as they were seen by Christian pilgrims, researchers and scholars.

“We have maps of Jerusalem from a very wide time range,” Dr. Levy-Rubin says before pulling out one of the most ancient and special ones—the monk’s map. “There are different types of maps, which may have entirely different purposes. A map is absolutely not objective. Sometimes, there’s an attempt to present the city ‘as it is,’ while other times people give that up in favor of an imagined Jerusalem.”

“Today’s commitment to the scale of a map and the direction it is drawn from did not exist up until 200 years ago. So in many cases, people look at the maps and say: ‘It’s not a map, it’s a drawing, because it has a panoramic outlook.”

Who sketched the maps of the city of Jerusalem in old times? Christians in general, and Catholics in particular.

“The Christian world developed a strong map-sketching tradition,” says Dr. Levy-Rubin. “Some of the sketchers were pilgrims who actually visited Jerusalem, and some were researchers and scholars who studied Jerusalem’s structure in biblical times and in the days of Jesus and then tried to recreate it.

“There are no Jewish maps of Jerusalem at all,” she stresses. “While there are different drawings of the city, there is no map. In the Muslim world, there are mainly illustrations of the Temple Mount itself, but again—not of the city.”

The monk who sketched Jerusalem

Jerusalem’s centrality in Christianity is immense, according to Dr. Levy-Rubin, particularly in light of the accounts of the last week in Jesus’ life, which all happened in different places across the city. “Jerusalem is the stage of the most important occurrence in Christianity, and this pinnacle is something every good Christian would like to imagine. This is where the maps come in.”

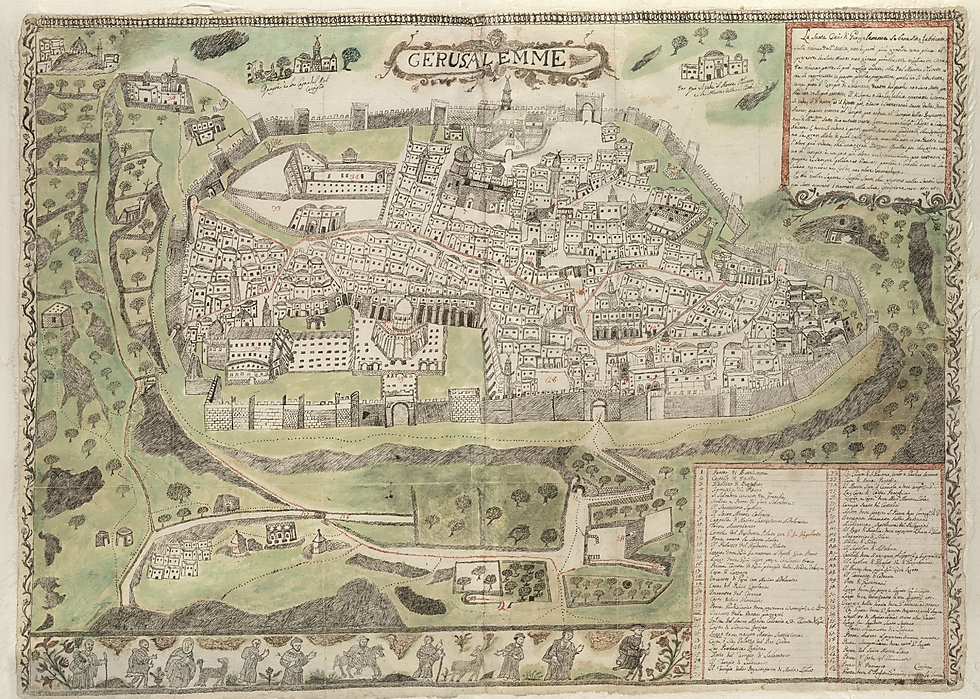

The “monk’s map,” a drawing from circa 1590, is the first map presented by Levy-Rubin and is considered one of the most ancient maps in the library’s collections. Although its illustrator remained anonymous, researchers believe he was a Franciscan monk who lived in Jerusalem.

“It was drawn from the east, a bird’s eye view from the Mount of Olives, the area the pilgrims came from and watched the city. The map was drawn in the Mamluk period, when the city was under Muslim rule and Christians were not allowed to walk around freely. From the 14th century, the Franciscans assumed the position of the ‘guards of the Holy Land’ and took responsibility for the groups of pilgrims, hosting and leading them on closed routes which were agreed upon in advance.

"It’s a very naïve map,” Levy-Rubin adds. “It’s a simple and enchanting drawing, and you can see pilgrims on the margins. The map presents a series of important sites, and the red lines mark the routes the pilgrims were led on from one site to another. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher is rotated eastward, like in many other maps, so as to show the front which was in a different direction on the map. You can see the Franciscan compound in the northern part of the city, where the illustrator likely came from.”

The researcher points at the crescents (the symbol of Islam) marked all over the map. “It seems obvious, but most Christian maps have no interest in presenting the Muslim presence in the city. Rather, they seek to present Jerusalem to the virtual pilgrims browsing the book as they would like to see the city. In most maps, therefore, the Muslim nature of the city is concealed. The Dome of the Rock is called Solomon’s Temple, and the Al-Aqsa Mosque is called ‘the place where the Virgin was presented at the Temple’ (according to Christian tradition). This is a rare case in which that didn’t happen, although it’s a very Christian map which presents all of Christianity’s important sites. The city doesn’t look European either, and the building seem authentic compared to many other maps.”

A Christian vision of Jerusalem

Another special map in the library’s collection is attributed to a French diplomat from the court of King Louis XIV, named Des Hayes. “He was secretly sent to the East,” says Levy-Rubin, “and later wrote an account of his travels, including a map that he drew of Jerusalem. The journey’s description and the map were later published as a book in Paris in 1621.

“The special thing about this map is that it looks like the maps we are familiar with, showing the city ‘from above.’ It’s also very loyal to reality. It can’t be called an ‘accurate map,’ but it’s very accurate. On the other hand, unlink the ‘monk’s map,’ there is not a single crescent on this map, and all sites are presented in their Christian names, in a sort of oversight or deception of the viewer.”

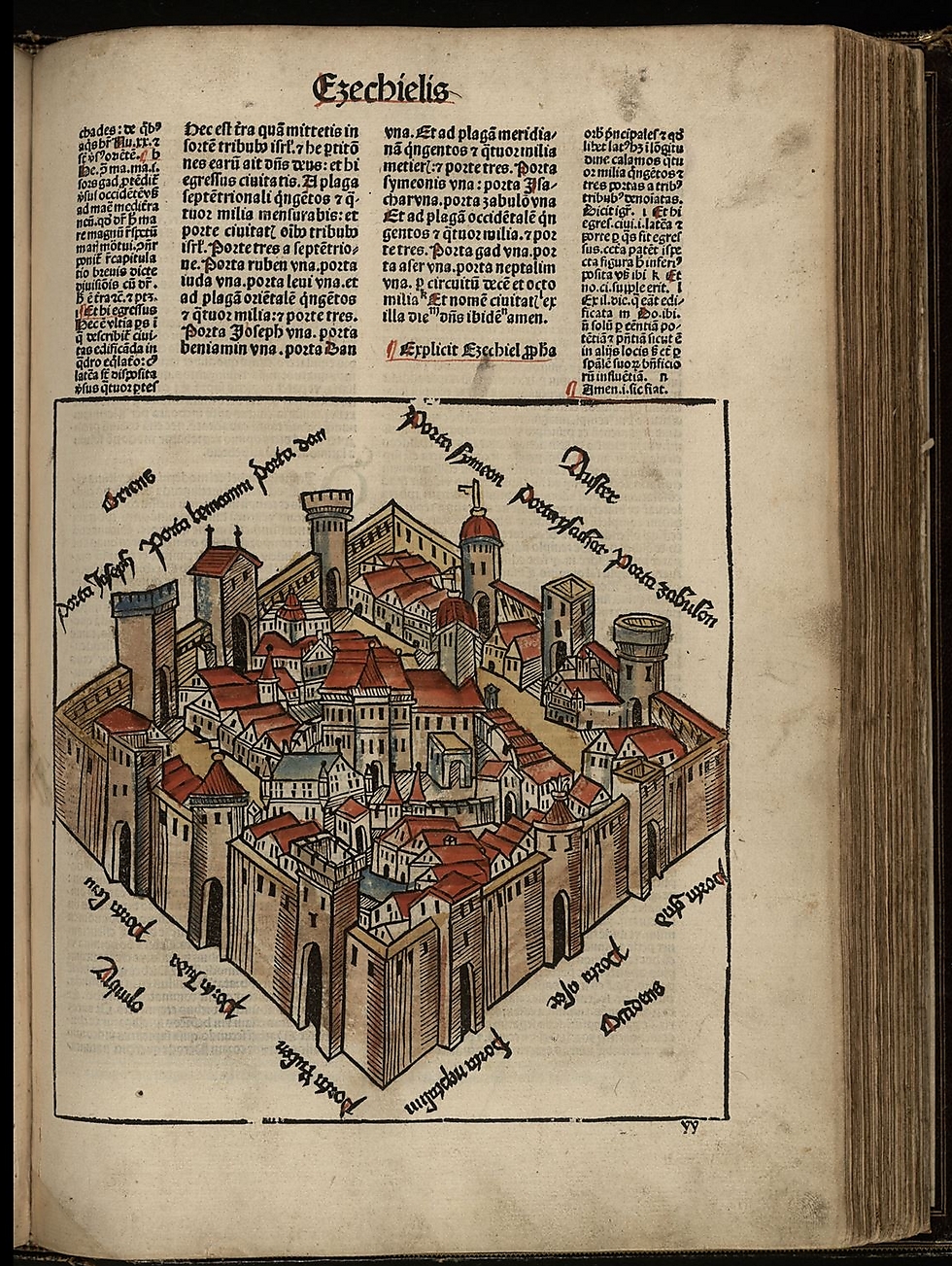

Unlike the accuracy of the French diplomat, who even visited the city, one of the ancient maps in the collection was created by a Christian scholar called Nicolas de Lyra, who lived from the late 13th century to the mid-14th century. It was one of the first maps printed in Nuremberg in 1487.

The scholar, a Sorbone graduate, was one of the most influential practitioners of biblical exegesis, who put a great emphasis on literal accuracy. According to Levy-Rubin, he used quite a lot of Rashi’s commentary in his work, and the map was found at the end of an exegetical commentary on the Book of Ezekiel, which included a detailed description of the future temple.

“This description sparked the imagination of many people, who tried to recreate the Temple accordingly. Nevertheless, the map is more characteristic of Jerusalem’s description in the New Testament, and it focuses on a description of Jerusalem as a whole and not just on the Temple. We see a symmetric city with 12 gates, one for each of the tribes of Israel. There is no structure describing a temple like in the Apocalypse of John, but only a beautiful city with fancy buildings. The city looks very European, but because this is an imaginary map of Jerusalem upon the arrival of the messiah, there is no attempt to reflect reality here.”

God’s view of Jerusalem

A more “modern” map, from 1734, was created by a publisher named Seutter, who used a model of Jerusalem drawn by two other scholars. “It’s basically two maps on one sheet. The upper one presents Jerusalem in ancient times, ‘Jesus’ Jerusalem,’ in a completely imaginary manner, from above. The second one offers a bird’s eye view of Jerusalem.”

Two-thirds of the sheet are dedicated to the ancient map created by a Spanish scholar named Villalpando. “There were no copyright issues at the time,” Levy-Rubin says, “so most of the maps are actually a more or less certified copy of someone else’s work. Of the 1,300 maps in our collection, half are copies of the same sources.

“Villalpando was a Spanish Jesuit scholar and architect. He wrote a famous exegetical commentary on the Book of Ezekiel and put a lot of work into recreating the Temple, which is why the map includes a very special drawing of the Temple—for example, the way he described the Temple Mount as sitting on huge supporting beams. Today we know, from an archeological point of view, that it’s a correct description. The entire view of the map is from above, but in a sort of orthographic projection—not flat, but three-dimensional.

“On the other hand, the map includes a mixture of different biblical eras. For example, the Greek Akra fortress, which was built to supervise the Hasmonean Kingdom, with the title ‘Salem, the city of Melchizedek,’ together with the City of David. He revived the biblical city in a mixture of times and places.

“Another interesting thing about this map is that he sketched Jerusalem and the Temple from the point of view of God in Heaven, which is an intriguing dimension. It should be noted that Villalpando was arrested by the Inquisition for ‘an erroneous commentary of the Holy Scriptures’ and was acquitted.”

“That’s not the only inaccuracy, of course,” Levy-Rubin points at the map on the bottom of the page, which is considered even less accurate. “It was likely sketched according to a model of Merian or Jason, which describes the Kidron Valley as a flowing European river with a wide bridge separating it from the city. There is, of course, no connection between the European imagination and the reality of the Kidron—a seasonal stream with very little water, if any, during winter.

“The bottom part of the map is presented as we described in the monk’s map, from a Christian point of view, with Gethsemane, the Valley of Josaphat and the Tomb of the Virgin Mary at the center, and the City of David on the right, and the pilgrims are seen walking with sticks in their hands towards it. Above the Dome of the Rock there is something that might be a crescent, but it’s the only crescent on the map. On the other hand, over the Church of the Holy Sepulcher there are crosses, which were definitely not around during that period.”

British ‘political correctness’

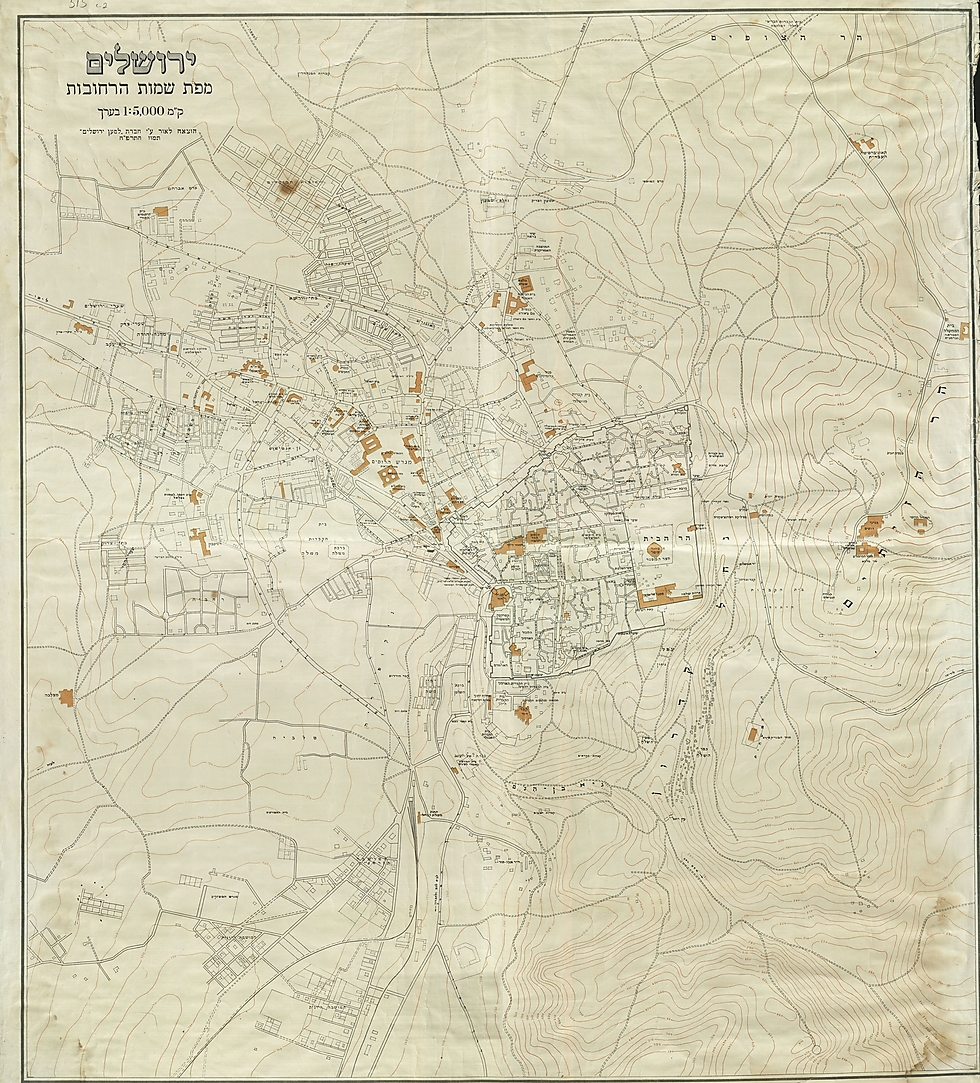

A British map from 1924 in three languages—English, Hebrew and Arabic—presents an almost complete identity between the three, and is loyal to reality.

“The Brits know that they are ruling a city which has both Jews and Muslims. The selected names are in accordance with the way they are known in the different religions. The Hebrew map, for example, says Har Habayit (Temple Mount), Misgad Omar (the Mosque of Omar), Misgad al-Aqsa (the Al-Aqsa Mosque, Urvot Shlomo (Solomon’s Stables) and Sha’ar Harachamim (the Gate of Mercy). In the Arabic map, instead of the Temple Mount it says Haram al-Sharif, and the Western Wall is Al-Buraq. The Gate of Mercy in the English and Muslim version is the Golden Gate (in accordance with the Christian version), and all the sites are marked on the map.

“The map also allows us to see the names of the streets in the British Mandate era: Today’s Ramban Street in Rehavia was called Gaza Road, because Gaza Street which led to Gaza hadn’t been paved yet. Hillel Street did not exist, but was presented as a continuation of Bezalel Street. The Brits intentionally gave many streets the names of crusaders and Christian kings. Ha Ayin-Het Street used to be called Godfrey of Bouillon Street, Julian turned into King David Street, and Melisende became Heleni Hamalka (Queen Helena of Adiabene).”

It’s very interesting to see the borders of the city in this map, as the Brits saw them.

“It is. The southern part of the city appears on the map only partially. The northern border is the Hebrew University, which was inaugurated in 1925, and the northeastern border is Augusta Victoria. The southern part of the city is presented as an empty area. There are no names of streets and there is no drawing of buildings and houses.

“Politically, it’s a very interesting map. The Brits are ‘playing the game’ here: On the one hand, they aren’t concealing any site. On the other hand, they are making sure to name all the sites in accordance with the city’s religious and political sensitivity at the time.”

- For more maps, photos and stories of Jerusalem, visit the National Library of Israel website (http://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/english/Pages/default.aspx).