The procedure of leaving Gaza went on for days. In the first stage, Dr. Mukhaimer Abu Saada, who lived near the upscale Al Rimal neighborhood, was forced to move with his wife Rosanne and his children to Khan Younis where he found shelter at a relative’s apartment. Two weeks later, IDF forces told the area’s residents to move to Rafah where the man, who until recently was head of the department of political science at Al-Azhar University, huddled with his family in a tent in appalling conditions.

Only then did they receive word and the family reported at the border crossing. They waited in line. Someone had made sure to pay $8,000 per person. Only then were they granted a permit to cross into Egypt. “It was a nightmare,” he says in an interview from his new home in Cairo. “We didn’t know until the last minute whether we’d be able to get out of there.”

Despite the upheaval, Dr. Abu Saada is considered one of the lucky ones. Since the start of the war, very few Gazans have managed to leave the bombed and burning Strip. Some only passed via Egypt en route to Europe or Arab countries that had agreed to take them in. Others have settled in Egypt. The transition cost a great deal – amounts of money most Gazans could only dream of.

Two weeks ago, the British Sky network reported that an Egyptian company named Hala received the monopoly for Gazan residents crossing via the Rafah border. According to the report, the amount per person is less than the amount Abu Saada paid - “only” $5,000 per person. “It’s not easy for a Gazan to get hold of this kind of money,” says Abu Saada. “And there’s another factor playing a role behind the scenes – the GSS, which wasn’t leaving anyone wanting to pass alone.”

Abu Saada doesn’t wish to provide precise details about how he and his family managed to cross the border. He is prepared to say that it was replete with pitfalls. Mid-journey, his middle son disappeared in the Gaza Strip, and didn’t make it to the crossing. They only tracked him down two weeks later when the family was reunited at the new address in Cairo’s Medinaty neighborhood. But even this reunion hasn’t reassured Abu Saada. “My heart is completely broken,” he says. “I left my mother, my brother, and his wife and children in Gaza. We’re in phone contact, but you just can’t tell what might suddenly happen. You’re constantly living with fear.”

Our conversation begins face-to-face in one of Europe’s capital cities. We carry on talking by cellphone – from my Israeli phone in Tel Aviv to Dr. Abu Saada’s Gaza number which has been kept in use in his new home in Cairo.

In Gaza, you were regarded as a prominent intellectual. What are you doing in Cairo now?

“I’m making arrangements in my new residence. We got here without basic items. We need beds, household goods, and clothes. We’re living in two apartments – my wife and myself with my married son, his wife, and a little grandson in one apartment, and the other four children in the other.”

Do you want to visit Egypt’s tourist sites? The pyramids?

“Trust me, I have neither the headspace nor the patience for wandering around. The first thing we need to do is get organized. Building a new life for nine family members in unfamiliar surroundings isn’t easy.”

He was born in 1964 in the Jabaliya refugee camp in the northern Gaza Strip. During the first intifada, he left for a master’s program at Columbia University in the US. He then continued to a PhD in Political Science and returned to Gaza in December ’96 after the signing of the Oslo Accords. “I was filled with enormous hope” he recalls.

Why did you decide to leave Gaza now?

“I’ll say it in the simplest of words – I don’t want to die.”

The home he has left behind is still standing, but “there’s a lot of damage to the house – doors have come off, windows have been smashed. the furniture’s moved around and has been broken. My son Alaa’s apartment, on the other hand - only 50 meters away, has been completely destroyed and has been turned into a pile of shattered stones.”

This must evoke very harsh feelings.

“Yes. My children are very angry with Hamas, but they also hate Israel.”

How would you describe the atmosphere in Gaza?

“Despair. Gaza won’t be able to go back to what it was before the war. There’s a lot of anger toward Israel and Hamas. I couldn’t even say who people are angrier with. We, the uninvolved civilians, are paying the terrible price for the war. On second thoughts, I can say that the anger toward Hamas is greater because of the destruction, the killing, people missing under destroyed buildings, the wounded, the hospitals that can’t operate, the doctors and nurses who’ve fled, and the terrible shortage of food and medication.”

As a leading intellectual in the Strip, involved in Gazan life, Abu Saada is very familiar with Sinwar’s character.

We view him as a cruel murderer, not interested in reaching any agreement with Israel. What’s your impression of him?

“Although I’ve only met him face-to-face once, I remember the meeting very clearly. It was in August 2018, just after the march against the blockade on the Gaza Strip that earned the moniker ‘The Great March of Return’. Sinwar invited a large group of politicians, academics and leading journalists to a meeting at his office. He updated us about the objectives of the ‘March of Return’. He spoke at length about Hamas’s goals and about the Palestinians from Gaza who had been killed and wounded. He proudly explained that Hamas had financed treatment for the wounded.”

“At the time, we didn’t know where things were going with Hamas. Sinwar had just been elected chairman in Gaza. I also remember him speaking bitterly about the plan to move the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. It genuinely irritated him. He also answered our endless questions in his short, to-the-point, style. But when he’d mention the word ‘Zionists’, or if the word ‘Israel’ would inadvertently slip out, I remember a spark of anger would light up in his eyes. You couldn’t miss it.”

Did you have the chance to talk to him on a one-to-one?

“At the end of the event, he went up to each participant and shook their hand. When he got to me, he used my name and said he knew who I was and in which department at the university I worked. I think he knew me mainly from my interviews on Al Jazeera. He seemed like a quiet, very stubborn man – the kind who wouldn’t be willing to compromise with Israel even on a single millimeter. He kept stressing ‘What I’m doing is for the Palestinians, and I’m not willing to budge’ So now, six years on, with this stubbornness I assume the story won’t end positively in Gaza.”

When asked about the events on October 7, Abu Saada doesn’t shy away from the using word massacre and calls Hamas’s operation a great, horrific, mistake. “I, personally, watched Israeli TV broadcasts for hours on end and can do nothing other than express deep sorrow. Now try to think how the October 7 massacre, and I definitely call it a massacre, caused the deaths of thousands of Palestinians. Some are Hamas people, and a large part are women, the elderly, and babies who aren’t involved and had no idea about what was going to happen.”

Since November, when the Rafah crossing opened for around-the-clock activity, 600 Palestinians holding dual nationality have managed to leave the Gaza Strip. Then came the privileged, like Abu Saada, whose people paid for their departure. At the moment, it’s the rich who can get out. At first, they paid $8,000 per person. The price then dropped to $,5000 and it’s now risen to $10,000 (children paying $2500). The permit arrives at night and is only stamped the following day. If you miss that window of opportunity, you have to start the process all over – with increments of thousands of dollars per person. Only a few dozen people have so far managed to get out in this way.

The few who completed the process and have managed to get out of Gaza are reluctant to be interviewed. They don’t want to reveal how they got hold of the amount of money needed and also don’t want to hurt or anger friends and family left behind.

Like Abu Saada, M., along with five family members, managed to make it to Cairo. “We were lucky,” she says, “we only paid $5,000 per adult and $2,000 per child. The price is now twice that.” She doesn’t want to disclose her complete name, and definitely not to an Israeli newspaper. “Yes, I’m in Egypt in a safe place, but I have first- and second-degree relatives in Gaza and I need to think of them.”

What do you think about what happened on October 7?

“At first, we didn’t know what really happened, just rumors. But when we gradually got the whole picture, we were shocked about the killing of Israeli civilians. For Hamas, there are no innocent Israeli civilians. And now we’re all victims of what happened there – Gazan civilians too. It wouldn’t be right to say that all Gazan citizens are Hamas. What have I got to do with them? I’ve never met anyone from Hamas. They’re usually underground and we’re in our homes.”

Tell us a little about life in Egypt.

“I don’t know how long we’ll hold out here. Good people have donated blankets and some old furniture. Neighbors come to ask if we need food. If my children bow their heads because they’re ashamed to ask, the neighbors will leave meals and drinks by the door.”

Are you thinking of going back to Gaza?

“I think everyone who’s left isn’t planning on going back. That part of our lives is over. That said, without passports, it’s very difficult to get out to go overseas, and managing a normal life is hard without a bank account. So, we might have to go back to the Gaza Strip. I assume going back there will be much easier than getting out, but who wants that?”

Fleeing Gaza naturally involves family members being separated. The rich and well-connected Fuad family for example split into two. The grandmother with her two daughters left the Strip, but the father refused to leave. “He decided to stay in Gaza to oversee the family real estate and building materials businesses. Despite the dangers, we couldn’t persuade him to leave” one of the family’s daughters tells me.

They’re presently renting in Cairo’s Garden City quarter. “We’re paying massively high rent – over $5,000 per month. The prices at the supermarket are five times higher than in Gaza. It’s unclear how long we’ll be here and whether we’ll go home at all.”

Are you treated as refugees in Egypt?

“Quite the reverse. They just keep asking for more money. Luckily, the apartment we rented is furnished, but we’ve had to buy clothes, shoes, and schoolbags for the girls who we’ve managed to register at the American school in Cairo.”

Back to Abu Saada, regarded as one of the most in-demand interviewees in Gaza: Even now, he’s getting endless requests from foreign and Arab news networks, mainly to help map out “The Day After” in the Strip. “To be honest, I don’t know what’s waiting for us” he confesses. “It all depends on a lot of factors. For example, will Israel manage to catch or kill Yahiya Sinwar? And what about Mohammed Def? Or Mahmoud Sinwar, Yahiya’s brother who plays a senior role in Hamas’s security forces? Further questions include how the negotiations in Cairo and Doha end, and most importantly – what will be the United States’ stance. I already feel the Americans have had enough of Netanyahu.”

Do you have any idea who’ll manage Gaza after the war ends?

“At this stage, I don’t know. But it’s important to note that Hamas hasn’t been completely destroyed. Hamas isn’t just the people managing the movement, but rather it’s mainly the idea. I can’t envisage, at least now, a possibility that Hamas won’t be part of managing daily life in the Strip. Even if you do manage to catch or kill Sinwar and the army leadership, Hamas will remain, and there’ll be replacements.”

“I’d like to bring up another point, that I think is no less important. Look at the war’s emotional damage. I have the feeling that Israelis have undergone an enormous change. There’s depression, great sadness, and a lack of hope that anything good is going to happen. That’s exactly what the non-involved Gazan residents are going through. Think about it – where will they build a home? How will they support themselves? How will they raise their children? Who’ll guarantee their future? Who’ll deal with their children’s distress? The women who won’t find themselves a place? The men and the elderly?”

So, what’s the solution?

“We firstly need a ceasefire and to release the Israeli hostages. I suggest releasing them all in one go and putting an end to the terrible suffering of the non-involved Gaza residents. No matter what Hamas gets, if they get anything, we’ll end up with no compensation for the extermination, destruction and terrible suffering of the last five months.”

Hamas claims they don’t know where some of the hostages are, and that some have been taken by “private people.”

“That definitely could be. You think Hamas controls everywhere in Gaza. That’s mostly correct. But over the past five months, they’ve been busy with the war and with hiding. It certainly could be that the Rafah residents who crossed the border and went into the kibbutzim, kidnapped Israelis and are hiding them.”

Who can lead the Palestinian people?

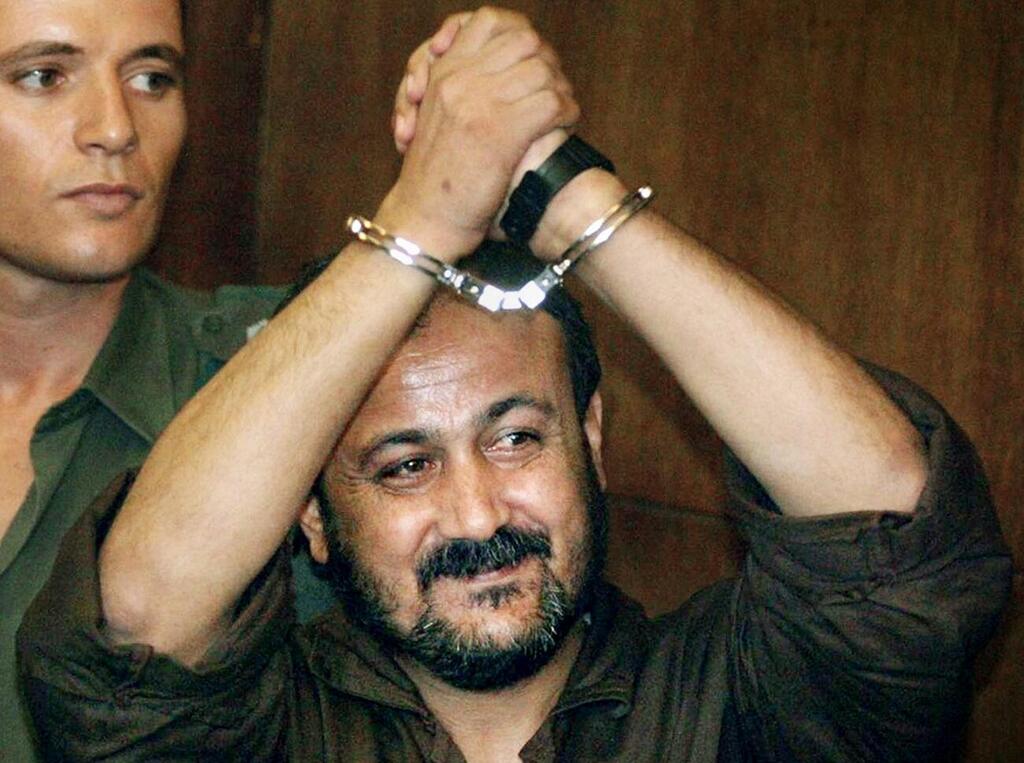

“I’m always hearing Mohammed Dahlan’s name from you guys. He’s from a refugee camp in Gaza and he deeply hates Mahmoud Abbas. I believe that, in the end, the real leader will be Marwan Barghouti.”

But he’s in jail, sentenced to life.

“He’ll be released despite the Israelis not liking the idea. He’ll be the one to make the reconciliation. There’ll be no deal with Israel without releasing Barghouti.”

Behind the permits and passes enterprise stands Ibrahim al-Arjani, who’s earned the nickname “Prince of Sinai.” He hails from a family originally from Gaza. He, himself, was born in Sheikh Zuweid in the northern peninsula. Al-Arjani is now friends and business partners with Mahmoud el-Sisi, the son of the Egyptian president. In 2021, he founded “Hala,” the company that deals with bringing Gazan residents into Egypt.

This isn’t his sole occupation. Al-Arjani controls tourism, vehicle, and food companies. He’s a member of the Sinai Development Foundation and is a partner in economic projects of the Egyptian army. A few short months before the war in Gaza, he was appointed to the Egyptian position responsible for rehabilitation in the Gaza Strip and started making preparations for building high-rise buildings and renovating neighborhoods. The war put an end to his plan, but he promises to be back after agreements are reached.

An interesting detail: Following a special request from Egyptian authorities, Al-Arjani’s 12-year-old daughter Tiba was brought, under a shroud of secrecy, last February for treatment at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem for a traffic accident injury.

And there’s another way to get out of Gaza – without paying. This is a secret route designed for Gazan residents born in Israel, or with mothers born here. To date, 71 Palestinians, mainly women, have gotten out of Gaza this way. They went into Egypt via the Rafah crossing, and from there they were permitted to enter Israel.

Alongside the few who managed to get the long-awaited exit permit, there are hoards still begging to flee the burning Strip. Many residents are writing on social networks, asking for donations to help them pay the amounts needed for the move. “I don’t know a family that doesn’t want to leave,” says one of them, Marwat Mamon. “We’ve lost the feeling of homeland. We need to flee. We hate Hamas just like we hate Israel. They’ve both caused this terrible disaster. And the world isn’t yet on board with helping us.”

Billal, a company manager in Gaza, also stands helpless in the face of the demands – some legal, some less legal. “There are eleven adults and children in our family, so I need to pay $85,000 - part as an ‘official’ payment and part as a bribe to people who’ll help us get the permit. We requested permits to get out of here three months ago and right now it’s looking a long way off.”

First published: 22:35, 04.29.24