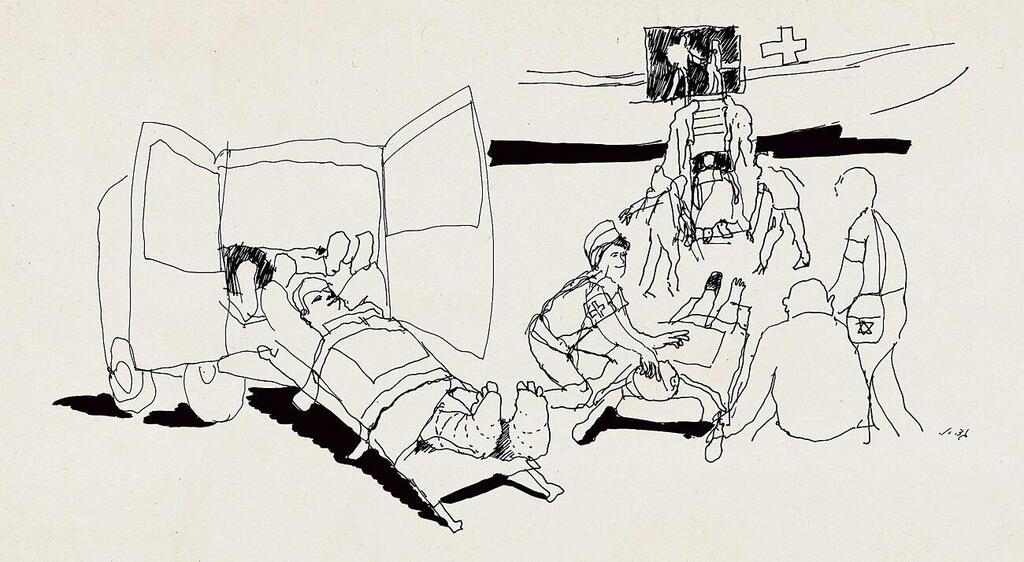

"We rushed from the airport to the Chinese Farm in a Dodge Commandcar. I still saw smoking tanks after the battle had ended. Then I became a rescuer, holding IV bags and talking to the wounded. Some conveyed messages to their parents through me. One had a severed leg and was in pain. Another had his eyes bandaged and whispered to me, 'What I wish for myself is to not remain blind.' People called this place the killing fields. Tanks were stacked on top of each other, like an archaeological site.”

Read more:

The Yom Kippur War caught Gad Ullman, then 38, in a synagogue in central Tel Aviv with his children. At the time, he was a graphic editor for Haaretz. However, the newspaper knew that in times of war, he was primarily an Air Force reservist with a unique role: a military artist. Wherever a camera couldn't be brought in, Ullman would arrive with transport planes and document the battles.

This wasn't the first time: during the Six-Day War, Ullman was actually allowed to bring in a camera, and his photographs appeared in various victory albums that were published afterward. "I shot what I wanted," he recalls, "since I was in a transport squadron, I lay on the floor and shot from the open door. I was the only one who photographed retreating Egyptian convoys."

Ullman, along with Yedioth Ahronoth journalist Simcha Aharoni, were assigned to a newspaper in the 27th Armored Brigade called Miznak. In the absence of printers, they would create a single edition, then duplicate thousands of copies using the photocopier in the commander’s office and distribute them. This method worked during the Six-Day War, and they thought it would also work on Yom Kippur.

"When the war broke out," Ullman recounts, "I went to the Air Force base from which the planes were taking off. The commander who received me said, 'Here, continue making the base's newspaper, Miznak.' It was clear that I would be going on the planes because I was 'their' journalist, from the Air Force, and could go anywhere."

Why draw instead of taking pictures?

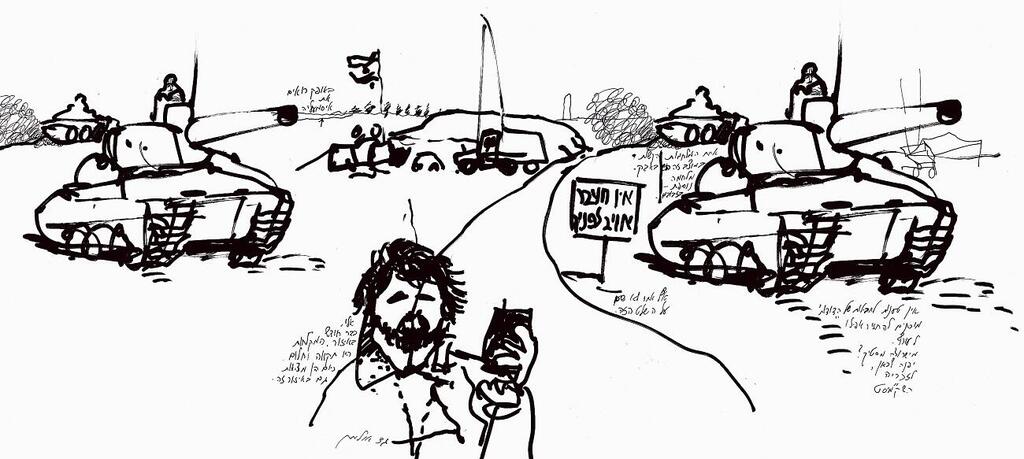

"There was very strict censorship and taking pictures was prohibited. Even my sketches had to be vetted by the IDF censor, and I had to sign on the back that I had not revealed the information to anyone else. The reason I drew instead of taking pictures was entirely absurd, especially by today's standards. Since printers were rare, we had to photocopy the Miznak newspaper, and because the photocopier couldn't duplicate pictures—since they would come out black—they asked me to draw. The drawings simply looked better on the machine."

Ullman, now 88, says he has always carried around a notebook and a pen ready for documentation, dating back to his school newspaper days. "I've been drawing from a very young age. When I was in flight school, from which I dropped out, I drew my friends. Some of them later became base commanders, important people. It was a given that Gad would draw everything he sees."

And so, when he randomly joined one of the planes, he noted for himself, "I got on an Air Force plane; we picked up wounded from the Chinese Farm. Who realized or knew that I was drawing history?"

Ullman's reports from the front were chilling, especially in real-time. "I didn't come from the position of a combatant," he says. "They sent and recruited me to create a military newspaper, I was given a role and became a documentarian on behalf of the State of Israel. My profession was to draw, but some things I saw, and people also talked, so I added handwritten notes to my sketches.

"Those same sketches that were printed in the abridged edition of Miznak, I would also publish in my column in Haaretz. The newspaper got me an essential worker permit, and twice a week I would return to Tel Aviv to produce the regular paper."

"I joined a cargo plane that became an air ambulance," he noted for himself on one occasion. "I helped transfer the wounded from the command cars that came from the Chinese Farm, and I saw from a distance the burnt-out skeletons of tanks. A horrific sight. It took me only a few minutes to emotionally capture that scene on paper. Since I am a drawer and not a photographer, I could bring the tanks closer to me. To zoom in with my imagination, as if I was actually on the battlefield."

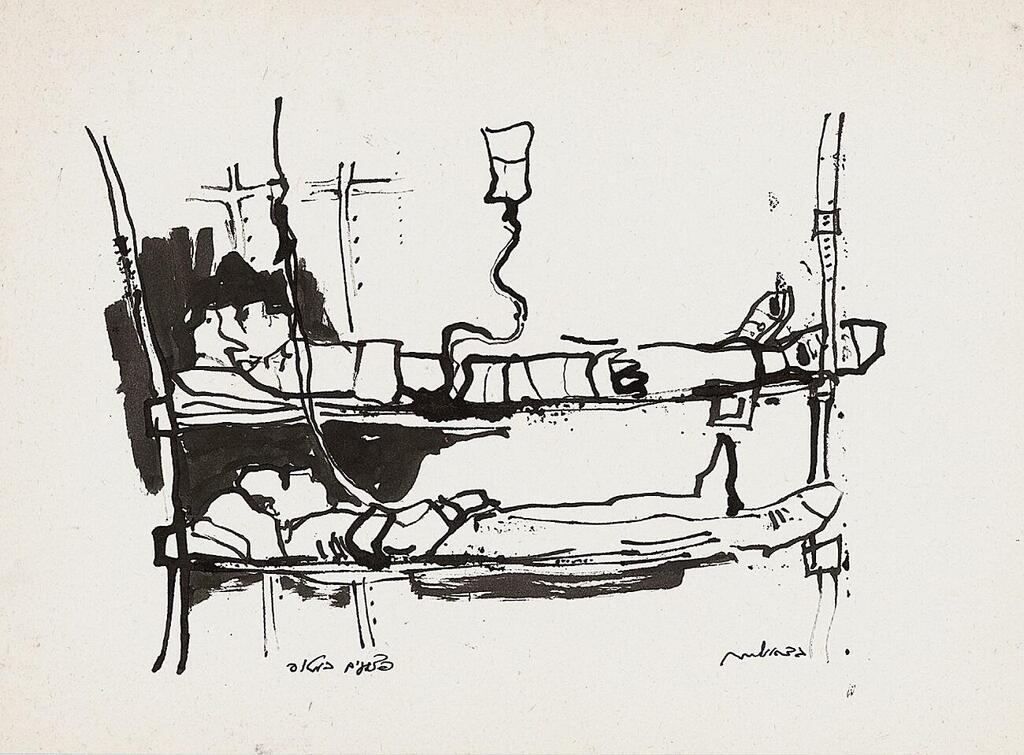

"One of the wounded said, 'We charged wave after wave, armor touching armor. My platoon commander was injured. A medic approached him to extract him but stepped on a mine, and everyone blew up.' I don't know how I found a brief moment to record the wounded on the stretchers. They were not screaming! Their eyes were open, sweating, teeth clenched. One of the wounded murmured, 'No air, no strength, no words’." In hindsight, he says, this is his most favorite sketch. "The drawing that best represents me."

The bravery of the wounded also caught his attention. "Ambulances were already stationed outside, ready to transport the injured to the hospital. One man, despite his injuries, resolutely refused to be evacuated. 'I won't go to the hospital for a single piece of shrapnel,' he declared. Similarly, an IDF officer, his face marred by burns and with an exposed bone fracture in his arm, disembarked from the plane standing upright and adamantly declined to be placed on a stretcher," said Israel, the coordinator of the ambulance service.

"The camera has its advantages and disadvantages," says Ullman. "There is no substitute for the freedom and excitement I feel in war. I was on a mission to bring these scenes to the people of Israel. You feel a sense of purpose, and you don't allow yourself to succumb to fear for your life. There's a certain vibration, an energy, when you enter a smoky room and feel as if the weight of the entire war rests on your shoulders.

"I was present at the moment the decision was made to cross over [the Suez Canal]. I heard Ariel Sharon say, 'We're going in between the armies,' and you're filled with excitement. Even now, I get excited when I talk about it.

“I reached the command center during an intense rocket attack. The sky was filled with the flashes of exploding rockets. I arrived at a dramatic moment in the command bunker deep within the mountain. [Major General] Gorodish, then the newly appointed Southern Command chief, was not in control.

“To his right was Brigadier General Asher Levy, and to his left was Major General Chaim Barlev who was sent to assist him. On the phone was the voice of Major General Ariel Sharon, demanding immediate crossing of the canal. Lieutenant General David Elazar and Major General Ezer Weizman were seen in the background. The air was thick with cigarette smoke. Phones were ringing off the hook. Indeed, this was the meeting that changed the course of the war—from defense to offense.”

First signs of victory

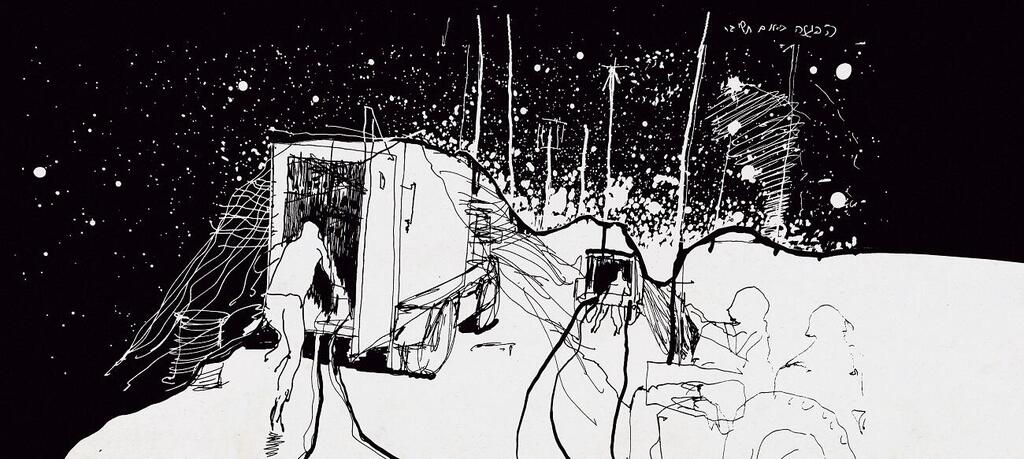

"The crossing of the Suez Canal was a heroic operation that cost a lot of bloodshed," he noted to himself. "In fact, three bridges were erected one after the other. Under the cover of night, they built the Galilee and Dubrovnik bridges, and only at daybreak did the vehicles and tanks cross over them.

“A soldier named Sasson told me, 'One tank fell into the water, and I will never forget the tank driver's eyes wide open with terror.' The bridges were the spearhead to push forward across the canal, in the direction of Cairo.

“Unfortunately, I arrived during daylight hours, after the crossing. I saw a motley crowd of vehicles, ranging from military command vehicles to supply trucks, from Russian war spoils to private Volkswagen cars."

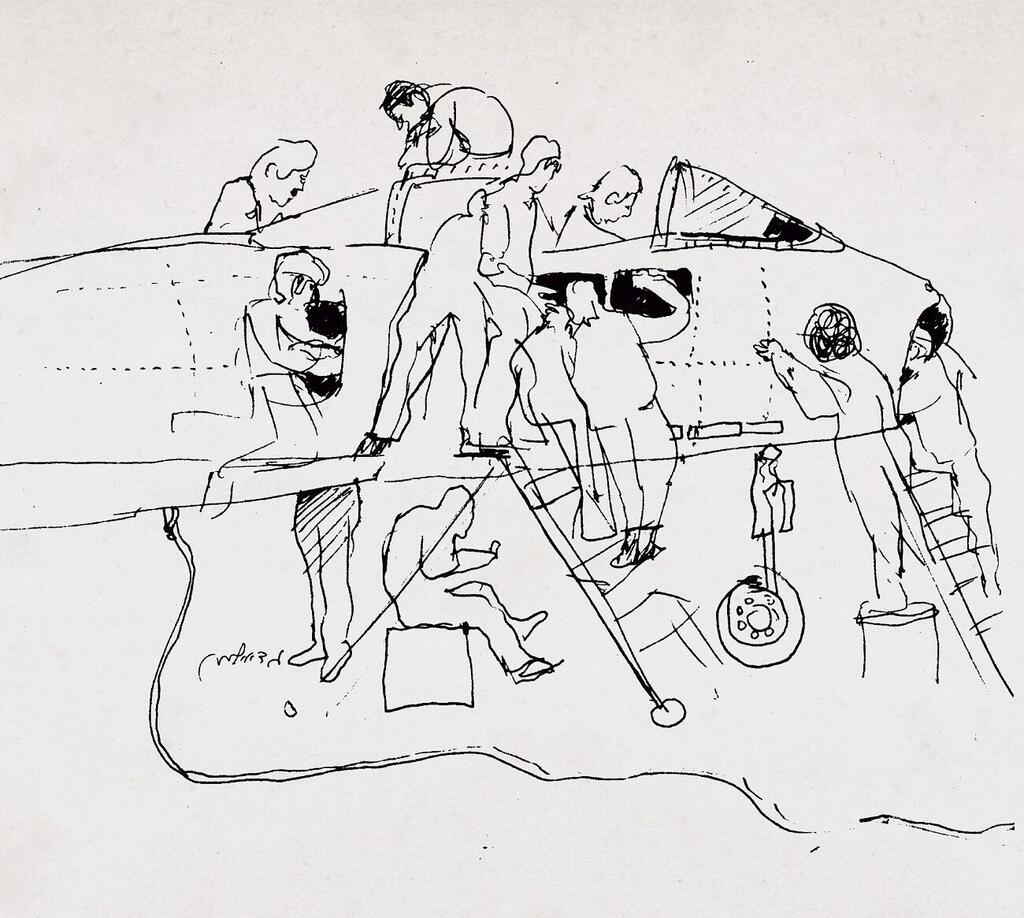

Next to another sketch, Ullman wrote, "Unbelievably, Israel is operating a huge airfield named 'Fayed,' located on the western side of the Suez Canal near Cairo, which has become the central air command. Flights are going non-stop to and from Israel. Cheetah [Eliezer Cohen, who would later become a member of the Knesset] the commander of the airfield, instructs on the destruction of the hangars in line with the ceasefire agreement with Egypt four months after the outbreak of the war. I stood on top of the hill to photograph the explosions. A disheveled soldier passed in front of the camera at the moment of the blast. Only the drawing remains."

On October 19, 1973, 13 days after the outbreak of the war, Prime Minister Golda Meir already said, "I see the first signs of victory." On the same day, Ullman drew the squadron commander pointing at maps in front of officers and pilots. "The arrows have turned; instead of the invasions in the first days of the war, now we are rushing toward Damascus and Cairo."

"All the books," says Ullman, "were written about the first days when we were caught off guard, and indeed there was shock in those initial days. But within a few days, we adapted. There was also a big difference between those who were at the front and those who were in the rear. The newspapers in Tel Aviv were in a kind of shock, but in the army, you are fighting; you're in an atmosphere of 'it’s payback time, let's turn the tide.' They were not concerned with the major implications that Yom Kippur has today.”

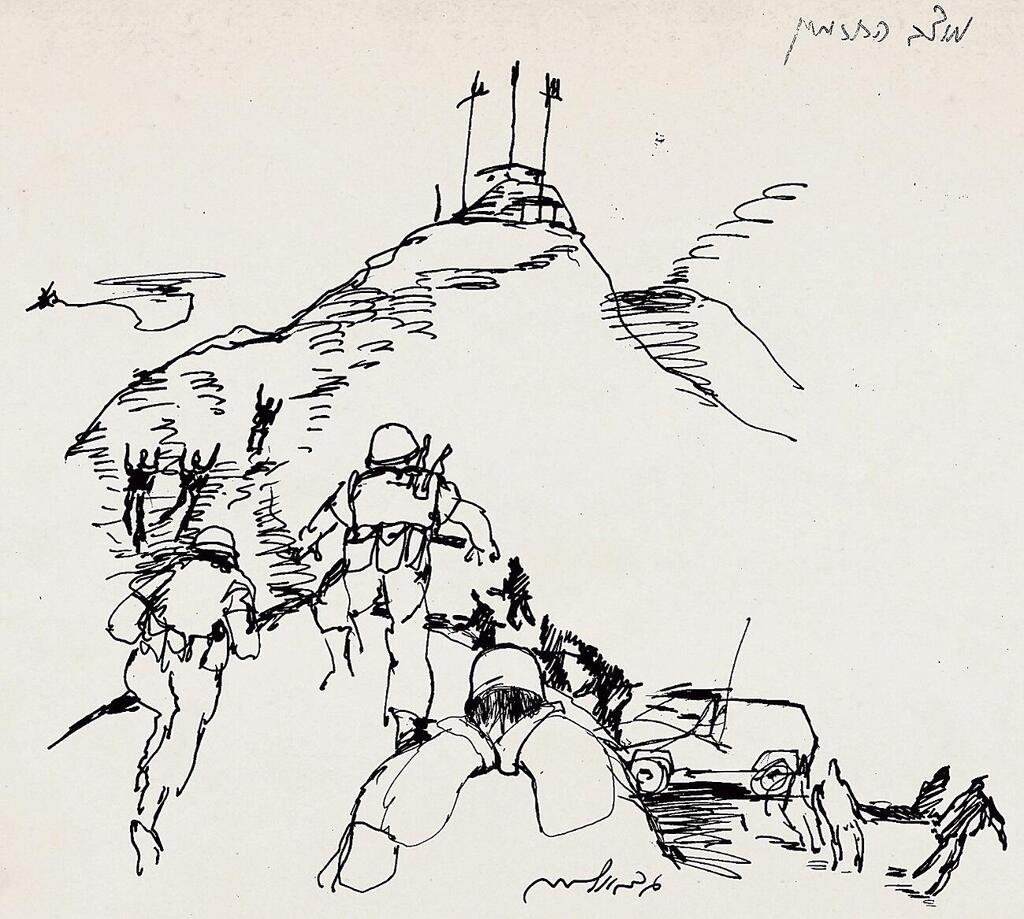

Ullman did not stay only on the southern front; he also reached the northern front with the Syrians. "I got to the Hermon outpost only after it was liberated from the Syrians, who had captured it on Yom Kippur itself," he says.

"Avi, a soldier in the Golani Brigade who fought in the first attempt to liberate Mount Hermon, told me, 'We felt like ducks in a shooting range. We didn't expect such firepower; we naively thought it was the seventh day of the Six-Day War.' Mt. Hermon was only liberated at the end of the fighting, on October 22.

“Then I met Zvika the sapper. 'We felt like cavemen or Eskimos. All the time in the igloo, we didn't know when it was day or night, artificial light, filtered air. Even the conventional measure of time—the news—was mostly impossible to hear’."

Obsession with Sinai

After the war, Ullman struggled to return to his regular life. "The documentation had a big impact on me. I became obsessed with Sinai. I would go down there, collect stones, boards, put them in my pockets, in my backpack, make works out of them. I had to unload the things I had seen from the side.

“I would enter to draw in places where censorship didn't allow photography. For the newspaper, I had to be objective, but not in my works. I went through trauma. I would go down with my car, travel early in the morning until I reached Sharm al-Sheikh and return in the evening. That's how I coped."

For many years, the drawings were stored along with other stuff that became—and sometimes did not become—works of art. He served as a graphic editor at Haaretz until 1983. He continued his reserve duty until 1990, when he was 55.

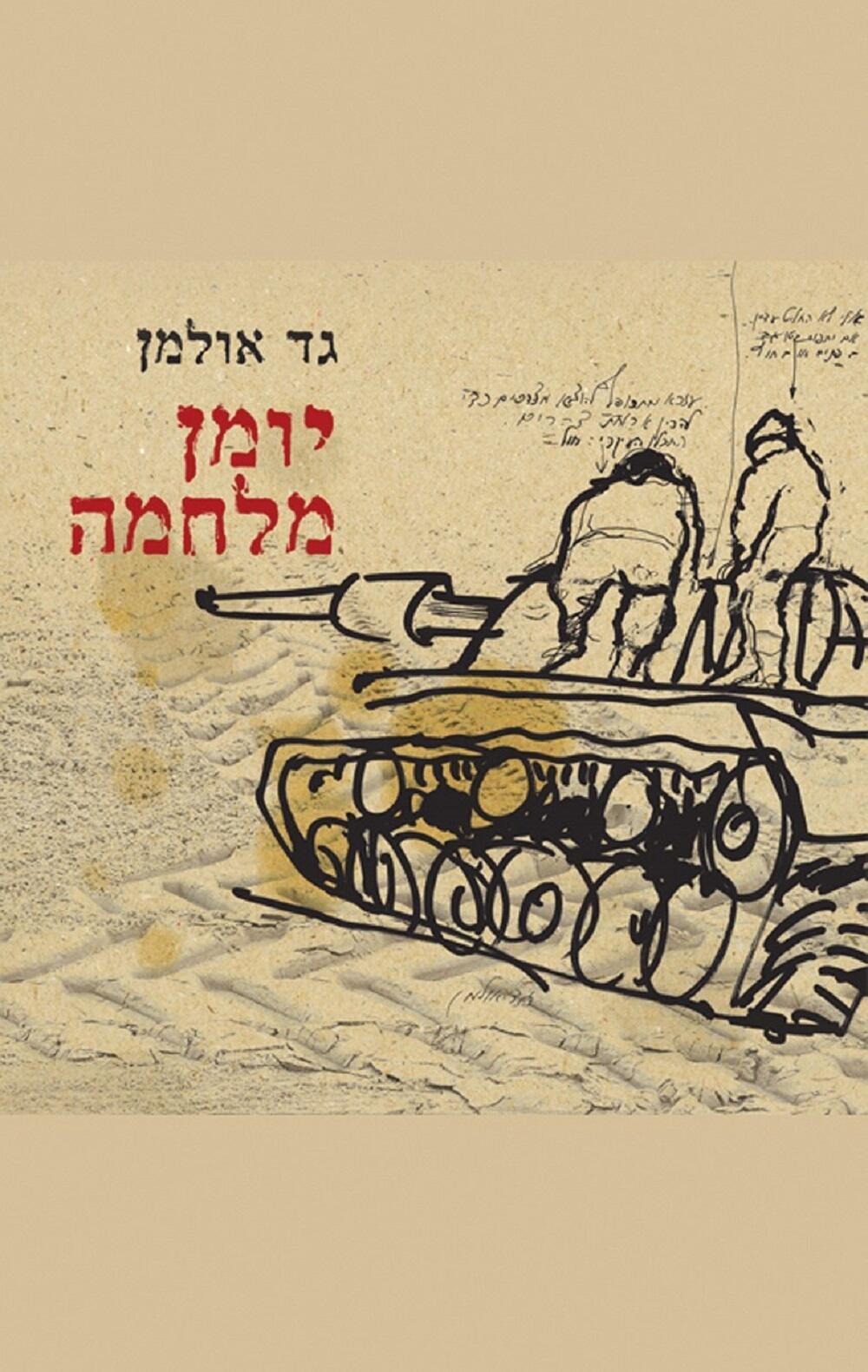

In the years that followed, he exhibited works based on the war in various exhibitions. Less than a year ago, when he was already in the ninth decade of his life, a decorated artist with a prolific career, he received a phone call from curator Orly Azran, who asked him to display his works in the exhibition War Journal, which would focus on the Yom Kippur War.

Ultimately, in addition to the sketches, Ullman also contributed to the exhibition a charred typewriter that he found in Sinai after the battles. The exhibition also gave birth to a book of the same name (published by Yedioth Ahronoth), featuring his illustrations and writings.

"I think I am lucky," says Ullman, "It's no coincidence that my name is Gad, which means luck. I know how to be in the right place at the right time."

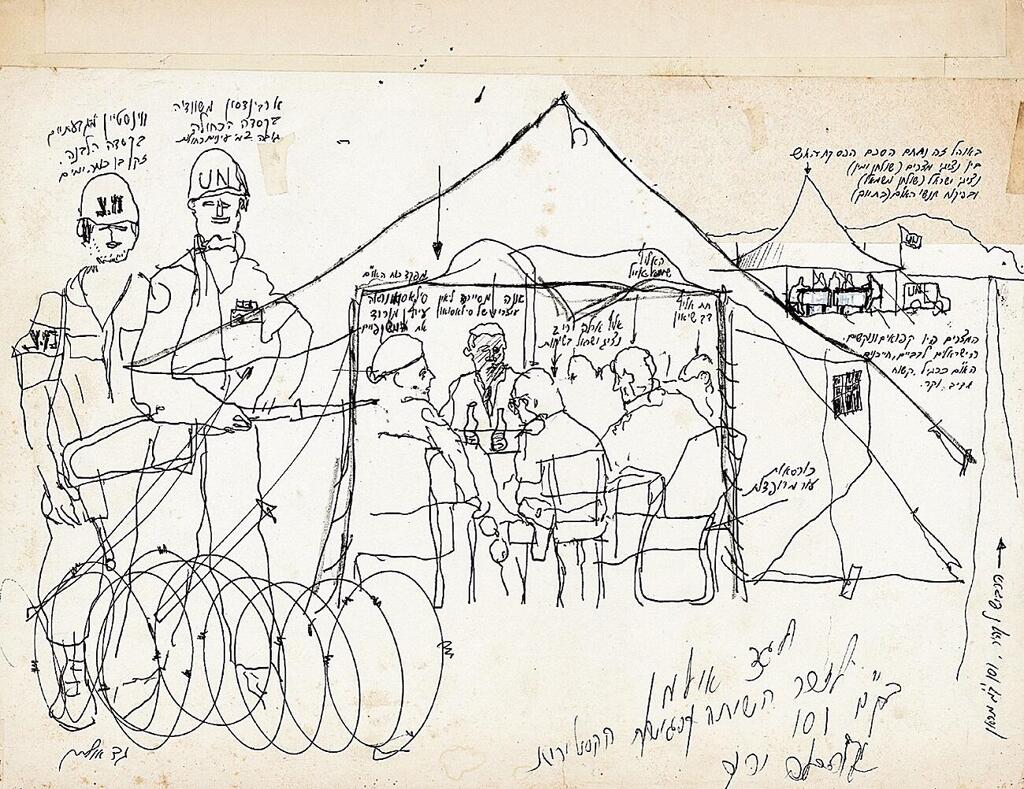

And he is not wrong. "In a roundabout way," he wrote in his notebook in '73, "I was present at the ceasefire talks, which took place on the 19th day of the Yom Kippur War. Where? At kilometer 101 from Cairo, on the western side of the ridge. A few tents in the middle of nowhere, the wind swirling. The Egyptians are on the right side of the table, stern-faced and tough, the Israelis cheerful and smiling on the left. In between them, representatives of the UN.

“Major General Aharon ‘Aharale' Yariv, Israel's representative in the talks, is very excited, signing at the bottom of the notes 'In memory of the historic meeting.' Next to a wire marking the entrance, the guards stand tall and upright, holding their firearms. Arbinson, the UN representative from Sweden, and Wonshtein from the IDF are also present. Everything looks like a stage set; will it be dismantled tomorrow at the end of the show? Yes, but they will return and rebuild it after four months, and right here, they will sign the peace agreements between Israel and Egypt. The end of the war."

“’Yom Kippur War' is a big name," he says. "There's debate about how long the fighting days lasted in the north and the south, 21 or 24. The opening illustration of the book, the soldier with sunglasses, was actually the last one I drew. Its title was 'Shock,' and it also appeared in the Haaretz supplement at the end of the war. The fictional tankist drawn here doesn't know what's going on; he has no eyes. He best represents, in my view, the concept of 'the Southern Front’.”

Did the war make you a better editor? A better journalist? A better illustrator?

"It made me a much better artist, but that didn't manifest in the newspaper because the constraints there were tough. There was no room for expression. However, they did give me a free hand, and once a month I would go down to the far south, to Sinai, to Nueiba, and come back with an illustrated article. As an artist, it was a mistake to be a documentarian. I realized that during the First Gulf War; by then, I allowed myself to be more expressive."

"At that time, my partner and I lived on Mazeh St. in Tel Aviv, and on the first night of the war, January 1991, a missile fell on Nachmani St., 30 meters from us. She said to me, 'Let's get out of here.' One of my models lived in Ramat Hasharon at the time and offered to host us at her home; she just didn't mention that the entire building was under renovation and that due to the war, the renovator had simply left the doors, paint and brushes, and left.

Everything was covered in nylon so I took the paint the renovator left and drew freely on the doors. I later made it into an exhibition, and it was even covered by CNN. These were essentially the Yom Kippur War paintings I hadn't made in real-time."

Today, when you hear about war or an operation, are you itching to be there?

"I don't want to be there. Sometimes I turn off the TV. I don't want to hear. Bombings and battles bring up unpleasant memories for me."

However, going back to that period did him good. "Ever since Orly Azran approached me, I haven't stopped engaging with it. Everyone focuses on the military aspect, but War Journal is an art book. When I look at these sketches, I understand the importance of drawing, that I can zoom in and zoom out. It's a different line, not the pretty line you draw at home. Since I got into this thing, I feel like I've shed 50 years. I wake up at 6:30 and go to bed late. I feel 38 again."

The book launch for War Journal, which contains Gad Ullman's war sketches, will take place at the Artists' House in Tel Aviv, on Saturday, October 14th.