For the first time in Jerusalem's history, a list led by Arabs is running in the local elections, which are scheduled to take place later this month, 5 years after the previous elections. If local Arab residents will take advantage of their right to vote, and favor the list, it will become the biggest faction in the city council. It would influence priorities and budgets, and benefit 40% of the city's residents who are the poorest and most neglected sector of Israel's "eternal united capital."

Read more:

Some two weeks after the Six-Day War, the government of Israel decided to expand Jerusalem's boundaries. East Jerusalem is now 70 km sq., more than ten times the 6.4 km sq. that made up Jordanian Jerusalem when the city was divided (1948-1967). The annexed areas were used to construct "ring neighborhoods" such as Ramot, designed to prevent future division of Jerusalem.

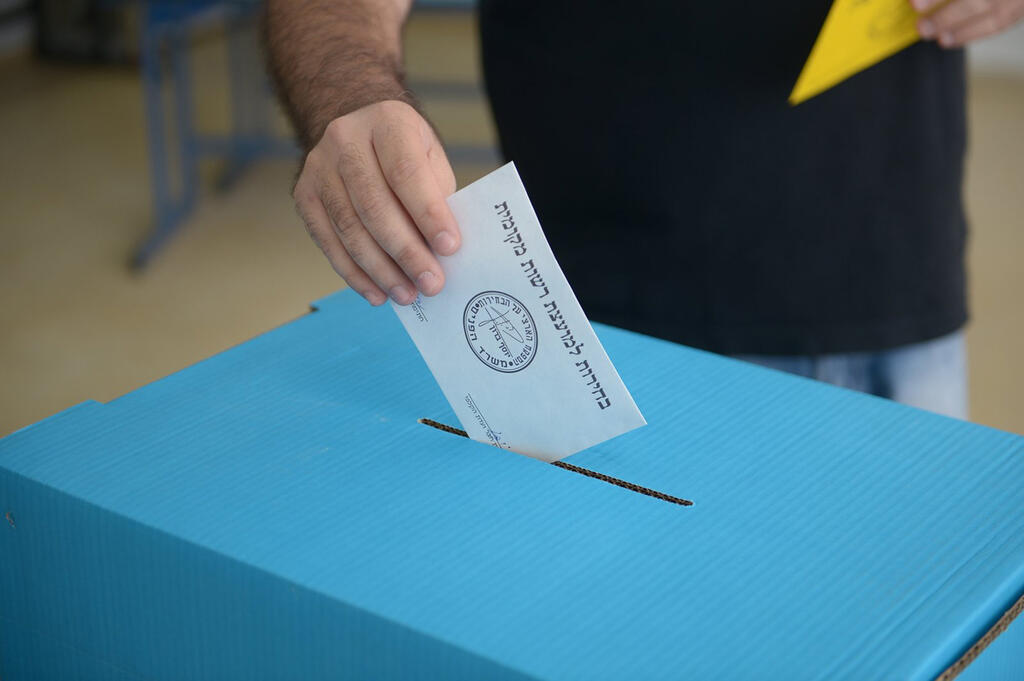

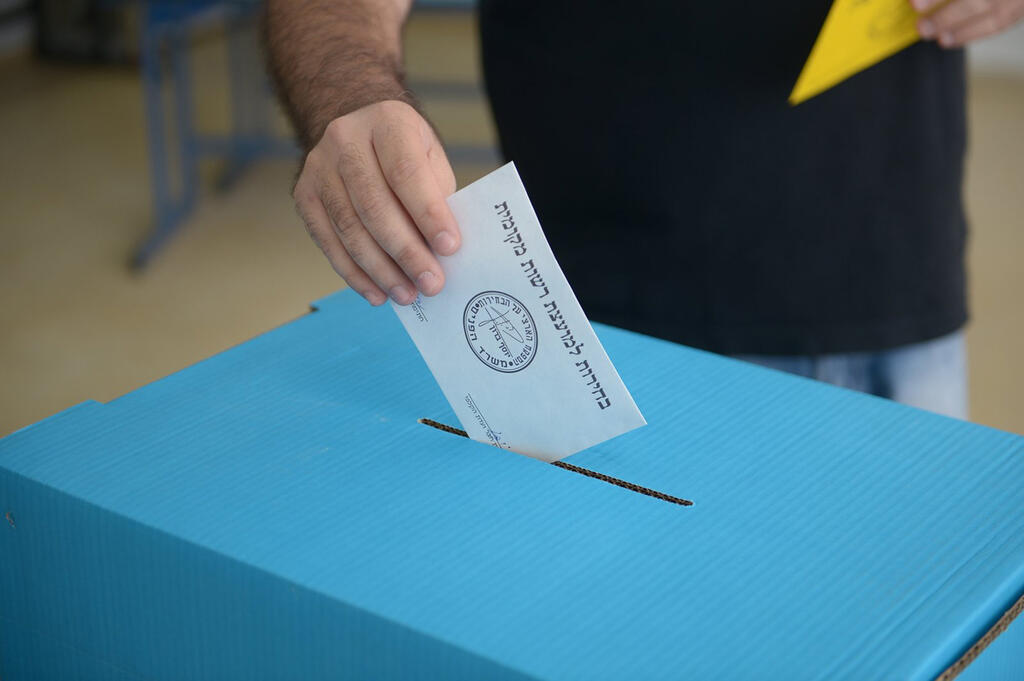

1 View gallery

Municipal elections in Jerusalem could take sharp turn in results

(Photo: Avi Rokach)

Other purposes included providing the capital with an airport. Qalandia (Atarot) Airport north of the city was built by the British during the Mandate, and later served Jordan. Due to international opposition to flights from an area that most of the world considers occupied, the airport was only used for domestic flights, and subsequently stopped functioning. But the annexed areas remain part of Jerusalem.

The road to the airport included Beit Hanina, Shu'afat, and the Shu'afat refugee camp, which became Jerusalem suburbs overnight. Israel attempted to draw the annexation lines to include as few people as possible, but now the combined population of these three locations is some 100,000 people.

They are about one-tenth of Jerusalem's million residents (double the population of Tel Aviv), and a quarter of its Arab residents. This is Jerusalem's poorest population, poorer than the Ultra-Orthodox and receives fewer services, as proven by a recent Five-Year Plan, which attempts to improve their conditions and to close noticeable gaps with their Jewish counterparts.

According to Israeli law, the annexed territories are fully Israeli. But in order to prevent the electoral influence of those who live in them, it was decided that they should remain citizens of Jordan, and become permanent residents of Israel. They do have the option of becoming citizens, but few want to. For those who do, it is a complex and rare process.

Following the Oslo Accords, this unusual Israeli-Jordanian hybrid was further complicated. Thus, Jordanian school programs that were in force before and after 1967 were replaced by the Palestinian Authority curriculum, with some schools following the Israeli program. Also, the security fence which was constructed following terror attacks of the Second Intifada, left parts of Jerusalem on its other side, away from employment and services, effectively in the Palestinian Authority.

In addition to eligibility for services like health and national insurance, permanent residents are entitled to vote and be elected to local authorities (but not to the Knesset). East Jerusalem Arabs rarely participate in the political game justifying their religious and political leadership's decision with opposition to the "occupation." Without representation, they lack the means to influence allocation of resources.

However, with time, this opposition has decreased. Thus, creating a list of candidates, which includes both Israeli citizens and permanent residents. Their objective, which mirrors Israel's official position, is to ensure equal municipal services such as welfare, education, paved roads and new neighborhoods although it is not entirely applied.

In a recent discussion about the elections, someone asked us to imagine an Arab mayor in Jerusalem. Frankly, I want a mayor just like me, which is why I was not happy when my city had an ultra-Orthodox mayor. However, they make up some 30% of Jerusalem's population, and in a democratic country, it is the right and duty of such a group to vote, be elected, and make a difference. This is also true of the Arab population, some 40% of the city's residents.

Tova Herzl

Tova HerzlMath will show that approximately 70% of the residents of Israel's capital do not identify with the Zionist vision that led to the nation's establishment, and/or do not carry the burden that befalls the remaining 30%. Israel's Declaration of Independence states that "the State of Israel … will foster the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants".

Fulfilling this vision sets a huge challenge before the leaders of the city and of the country, especially at this sensitive and complicated time.

- Tova Herzl is a former Israeli ambassador to South Africa and the Baltic countries, and served as liaison between the U.S. Congress at the Israeli Embassy in Washington

First published: 15:07, 02.16.24