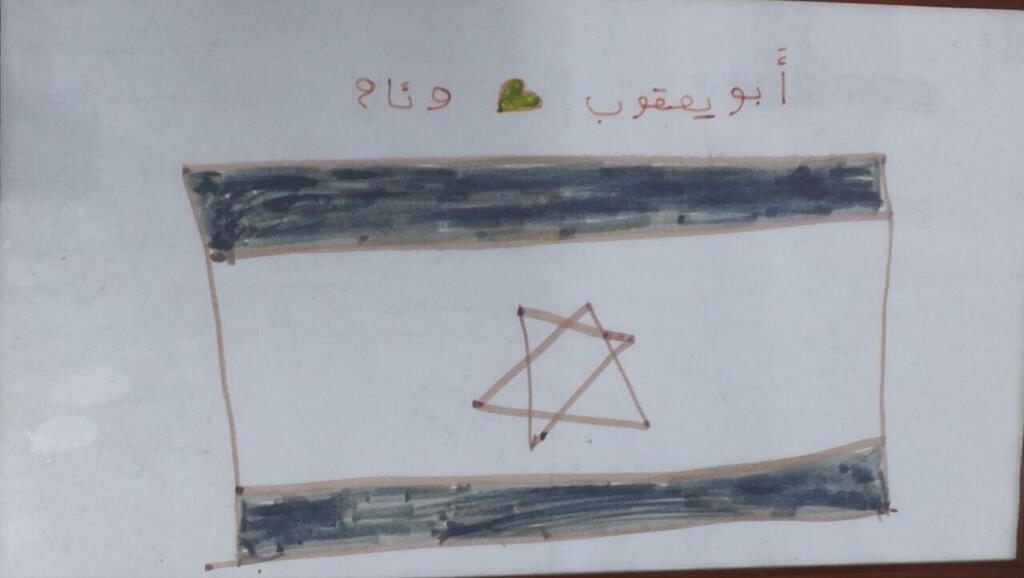

“We transferred a nine-year-old girl with Type 1 diabetes for treatment in an Israeli hospital back in 2016. One day, I met her and I was talking to her mother waiting for the doctor when the girl asked me, ‘How do you draw an Israeli flag?’ I explained. She asked for a marker and a sheet of paper and started drawing a Star of David. It wasn’t working out for her. She started getting annoyed and disappointed. It took her nine tries. At the top, she wrote ‘Wiam ❤️ Abu Yaakov,’ the name by which the Syrians knew me. This sums up the whole ‘Good Neighbor’ story: A girl from an enemy state, dedicating a drawing to an Israeli officer who saved her life.”

This quote is from Lt. Col. (res.) Eyal Dror, who headed the ‘Good Neighbor’ unit during the Syrian civil war. The December 8 overthrow of the Assad regime was indeed a stunning and unexpected ending to the 13-year civil Syria. Israel, however, had prepared for this moment years ago.

4 View gallery

"Those who were treated didn't want to go back, they cried, begged to stay"

(Photo: IDF)

The popular uprising against Assad kicked off in 2011 as part of the Arab Spring sweeping Middle East dictatorships. By 2015, Assad had lost control of most of his country’s territory, and it looked like his days were numbered. Israel prepared accordingly. With the help of Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah, Assad restored most of the territory he’d lost, pushing the rebels back to north-west Syria’s Idlib region, from where last month’s large-scale attack was launched.

More than half a million people have been killed in this war and millions of Syrians became refugees either in their own country or beyond its borders. Israel, for its part, quickly adapted to the new situation unfolding - with a border on whose other side some 250,000 people live every day in a combined state of chaos, danger, distress and uncertainty. But alongside the new threats posed were also new opportunities, including the potential for rare cooperation with the civilians across the border. The aim of “Operation Influence,” as it was branded by Lt. Col. (res.) Dror was to provide humanitarian aid in the recipients’ darkest hour - and also to try to make them realize the extent to which their perception of Israel was wrong.

“Cynics may say we’ve exploited their suffering,” says Dror, “but we’ve chosen to invest resources and risk lives for humanitarian aid. I knew they may well shoot me at any moment.”

It was named “Operation Good Neighbor.” As the civil war waned, however Assad, who had regained control of Syria, was looking like the great victor. Now, with his fall, our Syrian neighbor’s identity is, once again, changing before our very eyes. Although there’s no war going on in Syria right now, the nature of the emerging regime and the extent to which rebel leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa (Abu Mohammad al-Julani) has truly changed is, as yet, uncertain. Meanwhile, as Israel has taken control of the Syrian Hermon and the buffer zone, it would appear that the seeds planted back during Operation Good Neighbor, are still apparent on the ground. Syrians generally avoid confrontation with Israeli forces and have even been collaborating with them and requesting to be annexed to Israel.

According to foreign reports, Israel’s relationship with the Syrians was conducted along two axes, civilian and intelligence. “I took on the role of commanding the Northern Command four months into the Syrian revolt,” says Maj. Gen. Yair Golan, now Chairman of The Democrats party. “What was guiding us then, was the fear that the rebels would invade Israel.”

Only a month earlier, in May 2011, dozens of Syrians broke across into the Golan and were heading to Majdal Shams. In this incident, at least four Syrians were killed and dozens were wounded. “Our approach was that of fear and concern of further incursions,” says Maj. Gen. (res.) Eyal Golan. “So, we also reinforced the barrier, but I understood that cooperating with the rebels would better protect us. In this situation of ever-increasing chaos, the most important thing was having good relations with rebel militias east of our shared border. Militias who collaborated with us, whose operational activities we can trust so that we can be present in the field. They essentially acted in the interests of Israel’s security.”

These militia didn’t act out of Zionist sentiment. “Through a series of meetings held along the fence at my initiative, we understood that what they most needed was medical care,” says Golan. “They did have further needs - mainly food, clothing, and fuel for winter - but medical care was the most urgent. I tried advancing the idea with then Chief of Staff Benny Gant and was told no. In the end, we found ourselves facing a clear choice: One night, they simply placed six stretchers at the border. Then, 36th Division Commander Tamir Hayman called asking me what to do. I decided, not exactly with the Chief of Staff’s approval, to bring them in and send them to Ziv Hospital, and that’s what we did.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Contrary to Golan’s version of events, Gantz’s people say that Chief of Staff Gantz approved evacuating the wounded. “At first, due to opposition from the political echelon, Gantz personally approved admitting selected wounded - until he managed to convince the political echelon on the matter” they stated. “Later, in consultations headed by then Chief Medical Officer Brig. Gen. Itzik Kreis, Chief of Staff Gantz approved setting up a field hospital. The ‘Good Neighbor’ unit was later set up.”

Either way, what started as a pilot program, Golan says, resulted in the IDF treating more than 4,000 wounded Syrians over five years. The vast majority were wounded in the civil war, some extremely seriously. A smaller number showed up with other problems, such as childbirth complications. This is how the Syrians took off. According to reports, this was accompanied by intensive intelligence gathering, primarily by the Military Intelligence Directorate’s HUMINT Unit 504, responsible for obtaining human intelligence.

4 View gallery

Humanitarian aid in the snow. He also served an important security purpose

(Photo: IDF)

Golan says that collaboration with the rebels has been very fruitful. “It helped us understand that not everyone is Al-Nusra Front and Al Qaeda. They’re not all Muslim extremists to be feared, but rather quite the opposite” he says. “Most of the groups along the borders were Syrian Sunnis simply wanting to be rid of the violent and coercive Alawite rule and were so fighting the regime. In these years, they cleansed the border of all extremist elements, be it Hezbollah trying to infiltrate or extremist Sunni Islamic elements. They guarded the border alongside, not instead of, Israel, and did an impressive job.

As the Assad regime suffered blow after blow, Israel needed to cooperate with the new forces in Syria to continue its intelligence activities. As mentioned, the rebels provided Israel with a great deal of intelligence regarding what was going on inside Syria, in chaos at the time. These good relations led to Israel expanding its humanitarian aid, until it became somewhat of an institution with the 2016 founding of the Good Neighbor unit.

With its establishment, Lt. Col. (res.) Dror was appointed to command the unit, effectively creating a separation between the humanitarian aid and intelligence axes. Dror “borrowed” the new position from the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) responsible for activities with the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. This was due to the nature of the COGAT role, which involved contact with civilians, international organizations, government ministries, etc.

“At the end of the day, dealing with the civilian world is a profession unto itself,” says Dror. You need to be able to map out needs and adapt to each international organization according to its capabilities and requirements. So, someone from COGAT was chosen to head this unit and the job was precisely mapping the Syrian side, replete with its pressures and constraints.”

When you think about it, the IDF set up an HMO of sorts for the civilians across the border. Dror tells us that an Israeli doctor, along with his Syrian counterparts, professionally broke down what’s known as “Medical Care.” So, children with chronic illnesses were taken to the hospital and a ‘doctors’ visit’ of sorts was set up for specialist treatment. As it soon became apparent that women giving birth needed help, they were hooked up with international organizations that helped set up a special maternity hospital in the area. As family medicine was noticeably lacking, the IDF brought in an international organization to set up a field clinic where Dror says at least 7,000 Syrians were treated on an ongoing basis, and remote contact was made. “It’s not direct Israeli-Syrian contact, CT,” he says, “but for the Syrians, it’s clear who’s bringing them the treatment.”

The project treating children with chronic illnesses was the broadest. Approximately 1,400 children aged one month through to 15 were treated, usually accompanied by a family member. “At the end of the day, these are simple people,” says Dror. “Some are illiterate. Their lives are hard even without the war. In rural Quneitra, the standard of living is very low.” He says that lifesaving treatment was provided to 4,500 men, women,n and children, alongside the 7,000 treated in the field hospital, and that 1,000 babies were born in the field hospital.

Alon (assumed name) was a young Military Police soldier stationed for a month in 2017 at Nahariya’s Galilee Medical Center to protect the Syrian wounded coming into Israel. “I was still on the course. I’d been in the army for around three months” he says. “We were posted to an underground hospital ward. We were in civilian clothing with guns, and our job wasn’t necessarily to safeguard the environment from them but rather to protect them. We were instructed to protect them from the Druse, as some of them had fought in Syria and there was fear of retaliation. One day, as I was accompanying an injured patient in a wheelchair to surgery, suddenly a huge Druse guy started talking to him in Arabic. Before we understood what was going on, he pounced on him, knocked him off the wheelchair onto the floor, and started beating and punching him. We managed to separate them.”

He says that most of the wounded were men. “They explained to us that some of them would simply show up at the Israeli border and lie down, and IDF soldiers would bring them i,n,” he says. “Many were severely wounded. Some had lost limbs. Others had been blinded. They all declared that they’d been fighting against the Assad regime, but we had no way of knowing whether that was true and we occasionally interrogated them.”

He says that most of the wounded were nice and tried talking to the soldiers, but that the language barrier made this hard. “Some did learn a little Hebrew and they mainly said thankyou and expressed their appreciation for our saving them,” he says. “They got the kind of medical treatment they could only dream of. Some, when told they’d recovered and could be released, burst into tears, not wanting to go back, begging to stay.”

“I had 12-hour shifts,” he says. “I’d sit at an empty nurses’ station and would accompany patients from place to place. It could be for treatment, tests, surgery, or going out for a cigarette. Think about it, I was following 20 Syrians going out of the hospital for a smoke.”

What do you most remember about that month?

“I was once called in to receive wounded. We waited in the parking lot for the ambulance, and a couple from Syria who had stepped on a landmine showed up. The husband had improvised a makeshift wooden leg brace with screws for himself. His wife was heavily pregnant and had lost her legs, but she gave birth to a healthy baby in Israel. I’ve always wondered what happened to her and what they did with the baby. I wonder whether they received Israeli citizenship.”

With Assad’s renewed control of the area in 2018, the Good Neighbor unit’s activity came to an end, despite the situation in border communities not improving much. “The Assad regime has restored these communities over the past six years,” says Lt. Col. Dror. True, an Al-Rafid villager can make it to Damascus, which he couldn’t during the war, but this doesn’t mean he’ll receive services there. The area is poor and weak and the people there remember Good Neighbor and how they received help from Israel. We also have indications for this. We see it today. The big question is: What about the future? The situation today is fundamentally different as there’s no war there.”

Golan is certain that activity back then affords Israel credit points in Syria even today. “On an irregular basis, once every two or three weeks, I’d meet rebel leaders and visit the Syrian wounded in hospitals,” says Golan. “Many told us, ‘We thought you were the devil, and here, you’re saving our lives’. When we add up all the activity, the contribution to Israel’s state security is enormous”

Golan says, “Another important thing, somewhat eroded in the current war, is that we did the human, ethical right thing. We saved lives. We provided humanitarian aid. When you work correctly, at the end of the day, it also strengthens Israel’s security – and certainly Israel’s standing in international and regional arenas.”

Dror says that there are “1,001 scenarios” for the future of relations. “There’s no doubt in my mind that we’ve sown seeds that will yield fruit. I said this before Assad fell. I’m hearing this from Syrians overseas. The discourse regarding Israel is optimistic and they remember.

The Lt. Col. (res.) tells us that, while addressing a synagogue in Canada, he suddenly heard shouting in Arabic. He turned around and saw a man running toward him, who later turned out to be Syrian. “He said that he had to co, me,” says Dror. “He’d fled Syrian in 2015 and said that he’d read about what we were doing on the border, and just couldn’t come to hug me. He was a Muslim in a Jewish synagogue in Canada, simply sitting there listening to my talk. This was the moment I said to myself, ‘We’ve done something here’.”

There was another instance in 2018 when Syria downed an Israeli F-16, and a Syrian contacted Dror to ask him how the soldier who had been hit was doing. “Good Neighbor still affects a 17-year-old boy for whom we implanted a prosthetic limb seven years ago”, says the reservist officer. “That’s not the kind of thing you forget so quickly.”

Nonetheless, he says that more patience is needed. “I don’t know whether it prevented firing at our forces. There are lots more questions. Both sides, have to decide. The infrastructure exists. So does the professional know-how. Right now, it’s not a war border. In the past, we operated at night time, under heavy security, knowing that ISIS could attack us. This is the scenario we envisaged. The situation’s different now. I’m sure that if both we and they decide to move forward, we could do it on a gentle learning curve, and get it up and running in a short time.”

Syria, however, is not the only sector in which Israel has been operating on the civilian front. On October 7, the illusion of success in the Gaza Strip was shattered. This, inevitably also raised questions about the situation in other sectors, including Syria, as well as a great deal of skepticism as to whether reaching out a helping hand would, indeed, bring about stability and security. “The facts are that humanitarian efforts that also served for the defense were successful during Good Neighbor,” says Dror. “I can’t say what lies ahead. We all learned a lesson in modesty and humility on October 7.”

That said, Dror says that Gaza and the West Bank are fundamentally different from Syria and, although we mustn’t just stick with what we know, this is a tool that’s right to utilize. “Whenever I’d go down to the border during Good Neighbor and, in every interaction with the population, I’d factor in that the day may come that some guy might take advantage of the situation and turn it on me,” he says. “There’s no contradiction between the two and you have to manage by the situation assessment, consideration thinking critically, constantly checking yourself.”

Golan says, “In real life, nothing’s certain. It’s not like if the economic situation improves, you suddenly get more security. At the end of the day, it all rests on a tapestry of relationships, interests, trust, and worldviews. The overwhelming majority of people with whom we came into contact weren’t Islamic extremists, so the conversation was more on a personal and security level and less ideological. We yielded enormous security gains and, and the end of the day, ethically, we did the right thing. Amid what’s going on now, in Gaza and in general, that’s important to remember.”

“In the Gaza Strip too, not all Gazans are radical Hamasniks and nor are all Palestinians in the West Bank,k,” says Golan, as mentioned, now The Democrats party leader. “I think we need to be very wary of these dark areas. We should learn from our history and not implement an all-encompassing approach to Syria the Palestinians or any foreign entity on our borders. At the end of the day, these approaches don’t bring about security for Israel.”