Lital Porat was sure she knew everything there was to know about her mother, Israel Prize winner for theater, Orna Porat. But a surprise awaited her at a ceremony held with her cousins in Cologne next to the building in which her father, Joseph Porat (Proter) lived with his family who perished in the Holocaust.

More stories:

“We were invited to a building that had served as the city’s Gestapo headquarters, which has been turned into an archive and museum. We each introduced ourselves. When my turn came around, I said that I was the daughter of Joseph Porat and Irene Klien. Then the woman accompanying us said to me ‘You know your mother was interrogated down there…’ Taken aback, I asked: ‘What do you mean interrogated?’ She said to me: ‘There are cellars and Gestapo torture chambers and interrogation rooms.’ I’d never heard anything about this. We went down to this horrific place. It’s been left as it was, complete with fingernail scratching on the walls and instruments that you just couldn’t imagine.”

“When I asked why she was interrogated, I was told that she was working in a nearby factory and that she was sabotaging the war effort. She was apparently doing her own thing -dancing on the tables to raise morale for the poor Russians and Poles working there – as well as interfering with the factory’s production line. If it had been a Pole doing this – his end without trial, would certainly have been in sight. But she was a German Protestant.”

Why did she never tell you about this?

“I can only imagine that because she had a certain status in Israel, she didn’t want to show off or blow her own trumpet. She didn’t want to say ‘I’m not just a talented person of ethics and values. I’m a hero too.’ She was a genuinely modest person. And not a big talker.”

How modest was she?

“When I was little, I once went to a friend’s house – the daughter of a well-known actress. The walls in the home were covered with pictures, posters, statues and placards of the actress. When we got home, I asked my mother why we didn’t have pictures of her in our house. She said to me ‘Littleshen,’ – that’s what she called me - ‘why do I need pictures? I know what I look like. Once, after a première that had earned my mother rave reviews, my father asked her whether the success was going to her head. She just said ‘It’s nice, but what I’m really excited about is going to the market and the guys on the stalls saying to me ‘Ornalle, well done.’ That’s love. I’m not looking for respect.

Wherever you'll go, I will follow you

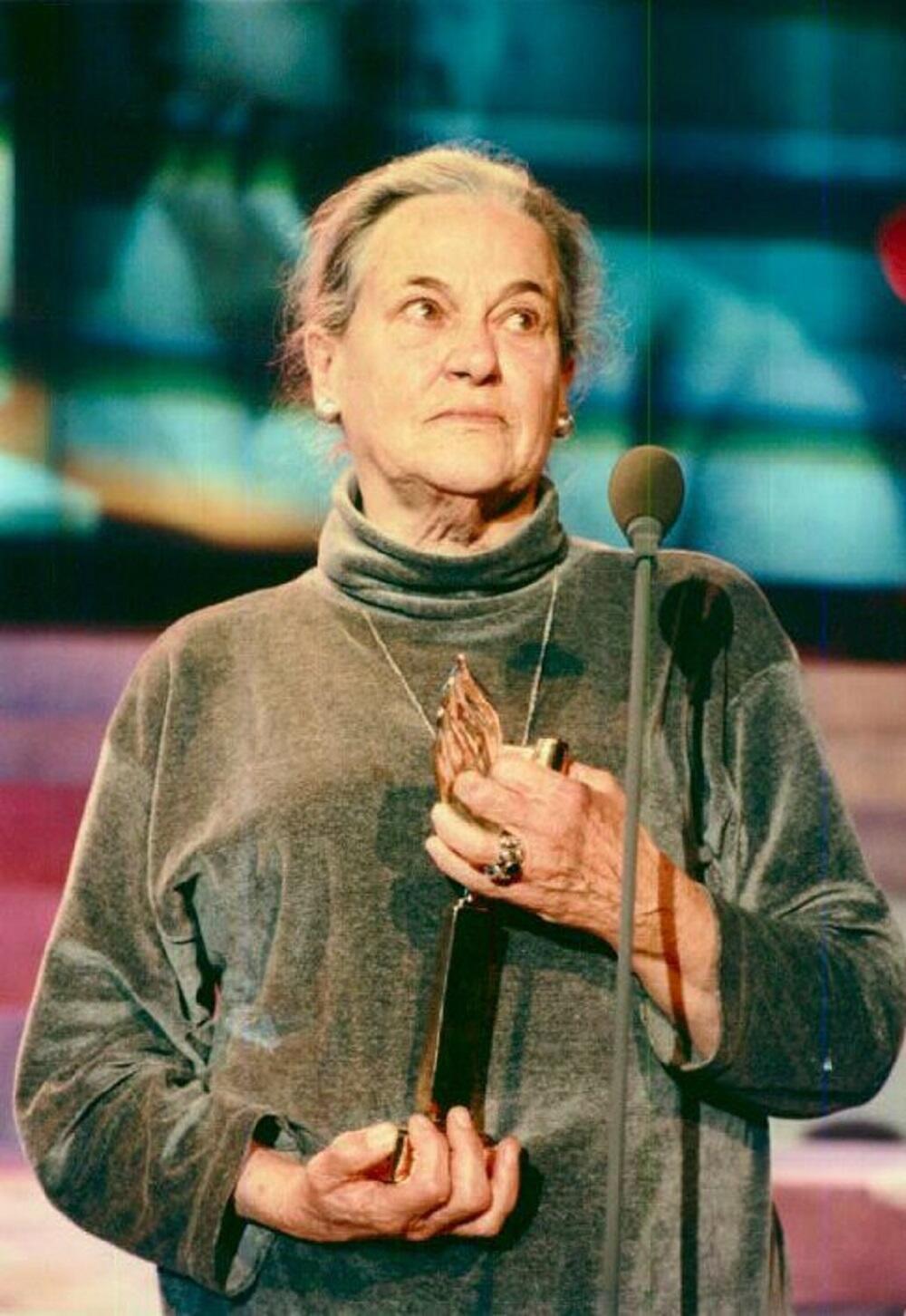

Porat, who ranks among Israel’s greatest and most beloved actresses, died nine years ago aged 91. She was born Irene Klien to a German Christian family in Cologne, Germany. As a patriotic teenager raised in Nazi Germany, Porat joined the League of German Girls (the sister movement of the boys’ Hitler Youth), proudly donning an embroidered swastika on her clothing. Despite her father’s protestations, she trained as an actress at the city’s theater school and, in 1942, was accepted to the theater in the city of Schleswig where she learned of the fate of the Jews in the Holocaust.

Lital explains, “When she worked at the theater, the husband of the woman in charge of the wigs came in. He was a guard at Bergen Belsen. He was shattered and broken, looking for his wife. He collapsed in tears: ‘Even if you kill me, I won’t go back there.’ He started telling them what was going on at the camp. My mother was startled and asked herself how could she pour out her heart on stage knowing that there may be murderers in the audience with blood on their hands. Her profession isn’t like being a shoemaker who can make shoes wherever he might be. She was an actress. Her voice, the very essence of her profession, rests on language and culture.”

A turning point for Orna Porat regarding the Hitlerite regime came with her acquaintance with the family of a Nazi officer where she carried out her national service following her theater studies. “After her national service, my mother was accepted to the theater. She kept in touch with the girls of the family” Lital tells us.

“At first, the officer would invite her to visit his office, like a good uncle, a kind of substitute father – or that’s what she thought. He’d also come with his wife to see her at the theater and would invite her for dinners. At first, he’d asked her, in a civilized and refined manner, about what was going on in the theater. After two or three such meetings, she began feeling that something wasn’t right about his questions.”

“One day, he said to her: ‘Let me know if any of your people tell jokes about our leader or if anyone says anything bad about the Nazis.’ He then took a pistol off the wall, caressed it and said: ‘And we’ll know how to deal with them.’

Her blood froze. She was stunned. Her whole world, the world in which she believed, collapsed. She went home astounded, saying to herself, ‘Okay, if he thinks I’m stupid, I’ll show him how right he is.’ On her next visit to his office at the Gestapo headquarters, when he said he wanted to know what was going on at the theater, she took a deep breath and rattled off a long monologue with all sorts of irrelevant details like about an actor whose button almost came off his pants.”

Orna also participated in active resistance, sometimes risking her own life. “My mother joined the underground anti-Nazi resistance, acting as a conduit, conveying documents, potentially placing herself in huge danger,” Lital tells us.

"She knew that if they caught her, she could expect to be tortured to the point where she would have to inform on her friends and handlers. At the same time, she had to report to the officer who tried to get her to inform on her friends at the theater. For a woman of her age, it was an almost impossible situation.”

After the theater was closed down on Hitler’s orders, Porat was sent to work in the Nazi military industry and operated searchlights to locate enemy fighter jets. Inspired by the Russians and Poles she met at the factory, after the war was over, she requested to emigrate to Russia. She was interrogated by a Jewish Brigade officer, Joseph Porat (Yosef Proter) who would later become a key figure in the Mossad and Shin Bet. He saw a completely German name and thought she was a Nazi trying to flee Germany. They fell in love and Porat followed him to Israel.

“My mother made snap decisions,” explains Lital. “She looked into his beautiful blue eyes and fell in love with him. She told me ‘I met my destiny.’ When a girl meets a boy, I see how the girl might think ‘wow, he’s so cute, I’m in love, my heart stopped’ – but not that she might say to herself ‘I’ve met my destiny.’ Her heart told her that this was a much bigger package deal. She converted to Judaism and added ‘Ruth’ as her middle name. She said to him ‘Where you go, I will go'.”

An unexpected turn of events

In 1948, Porat, by now an Israeli in the fledgling state, joined the Cameri Theater where she played a series of impressive roles. She went on to act in most of the country’s theaters. In addition to being a highly acclaimed actress, Porat also founded the Orna Porat Children's Theater which she also managed.

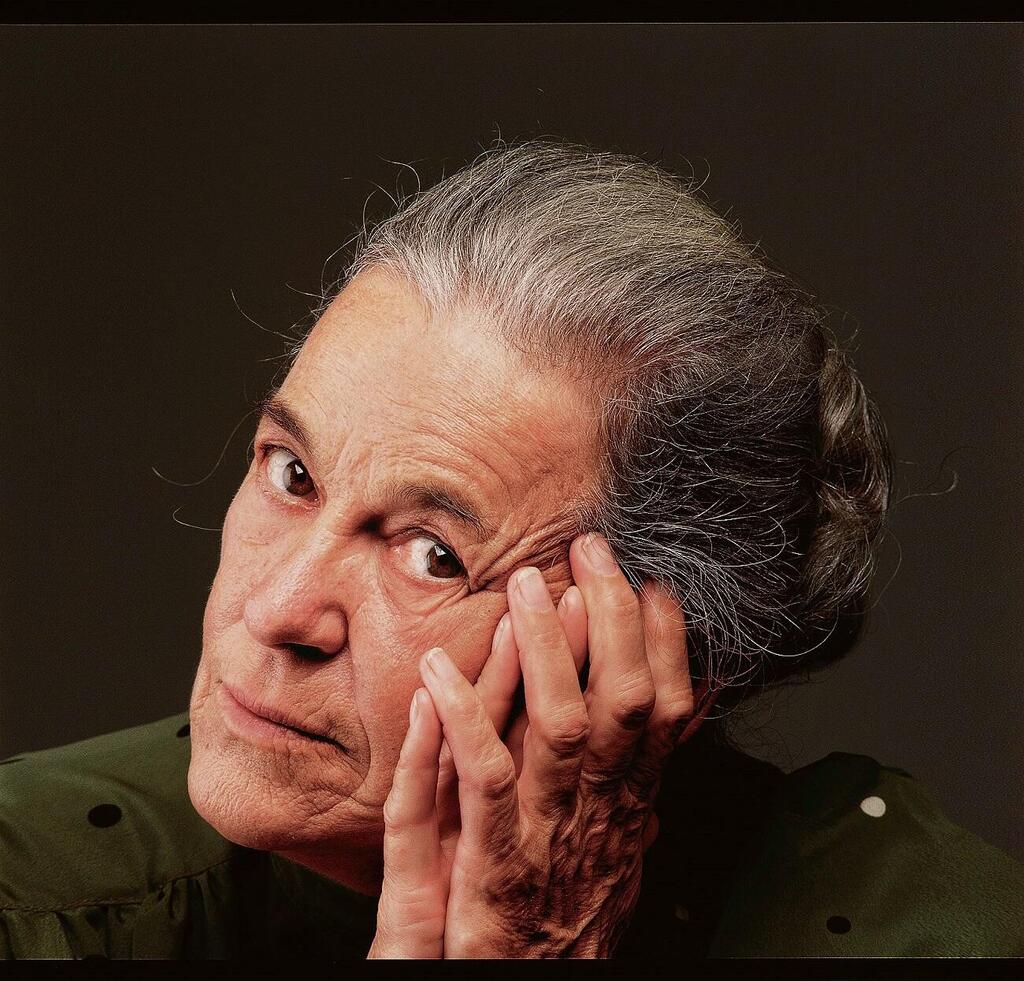

The first 21 years of Orna Porat’s tumultuous life are the subject of the book “Happy Birthday Dear Hitler” (Kinneret Zmora) penned by her daughter, Lital (65) who is a lawyer and playwright. Part of the book, which Lital describes as a “fictionalized biography” actually did take place. Other parts, are the fruit of Lital’s imagination. “I worked on this book for seven years, trying to put the pieces together.”

Why did you write the book as a fictionalized biography?

“My mother didn’t talk much, especially not about herself. The material includes things I heard from her and information I found in interviews and further publications about her. I was forced to fill in the gaps with my own imagination. She accompanied my father who served as a Mossad emissary in various parts of the world – so we don’t know much about that. These things will remain secret and confidential for a very long time.

She’d always joke that of the 40 years that my father was in her life, he was out of the country for 35. Information is available about my father’s work with the Mossad in Morocco. It was a rather funny kind of mission: My mother had to ‘act’ the part of an old German woman. If anyone can know more about my mother than what has already been written, I think it’s me.”

“If I’ve told a story that isn’t faithful to reality as events occurred, so it’s a story as it could have happened. Why did I choose my mother’s first 21 years? Because these are the most significant years in which her character took shape and when she underwent enormous changes. Writing the book brought us closer together – although she’s not been here for many years. One of the most amazing things for me while writing the book, was that on quite a few occasions, I learned that things had indeed happened as I imagined them.“

What would your mother say about the book?

“I think she’d say: ‘It’s okay.’ It sounds rather restrained, but then you’d have to see her face and it would be full of love, joy and acceptance.“

The Porats didn’t manage to bring children into the world. Orna, for fear of not being allowed to adopt because she wasn’t Jewish, decided to convert. Their eldest son, Yoram, was adopted in 1947 at the age of three. Nine-month-old Lital was adopted two years later. “People said to my mother ‘Why do you need a nine-month-old baby? Take a week-old baby, with less chance of damage.’ But she chose me and that’s the way it was.’

Did she ever tell you why she chose you?

“She said that I stretched out my hands towards her in the orphanage in Jerusalem and that it pulled on her heartstrings. I think she wasn’t sorry. We had our differences, but at the end of the day, our worlds connected. We even worked together. Little me, I was bold enough to direct her and write a play for her.”

Was being Orna Porat’s daughter difficult?

“It was different. My mother stood her ground. She had a very defined worldview. If I was told to go to bed at 6pm, I’d go to bed at 6pm. I was a bit wild sometimes – and being adopted didn’t make it any easier.”

“Her being so famous wasn’t easy for me. As a child, I was very much in her shadow. I’ll never forget one time we went to a social gathering and it would have been exactly the same if I hadn’t been there at all. No one talked to me because she was always the center of attention. It wasn’t her fault that she was so lovely, charismatic and famous. And the more amazing she was, the less anyone paid any attention to me. As an adult, I can only be thankful that it gave me a chance to develop, rise up and fly.”

How did children in kindergarten and school treat you as an adopted child?

“One day, a child in kindergarten said to me: ‘Your mother isn’t your mother, and she’s not Jewish either.’ I went home in tears. My mother went to the kindergarten and explained to me and to the other children that she chose me from among all the other children and all the other parents had to make do with whatever child they gave birth to. My mother being famous made the children hate me and they were a bit jealous.“

Did your mother want you to become an actress like her?

“No. She wanted me to do whatever made me happy. She’d say to me: ‘You want to be a kindergarten teacher? Why not? You’re great with kids.‘ She did encourage me to write. She asked me to write a play for her. I think we both knew that I had neither any acting talent nor any desire to be an actress.”

Your brother, Yoram, didn’t get on so well with her. He’s been very critical

“I’m not in touch with him. I’m not in a position to talk about him. We were never in contact very much. We were never proper siblings and it looks like we never will be. We see very things differently.”

When did you meet your biological mother?

“When I was 18, I toyed with the idea of meeting her. I only took the leap when I was 40, after my daughter, Yuval Or, was born – and I had something to hold on to. I was afraid it would be destabilizing. It actually was. This is the woman who brought me into the world and, like it or not, I’m connected to her. I have her blood running through my veins. She had a very hard life. She was a little girl during the war and made Aliya with the Tehran Children. I think it would be heartless to judge people in these circumstances – even though I paid a very high price.“

How many times did you meet?

“You’ve touched on a sore point. My meetings with her were very hard. I felt there was a lot of baggage and I didn’t know what I was supposed to be feeling. I also felt that she expected that when we’d meet, it would be very hard for me because I’d try to protect both of us. I stopped our meetings at some stage. I got on with my life, but I’d be lying if I told you I’m at peace with that part of my life. She has since passed away.“

Do you know who your biological father was?

“I do, but I understand that he’s not a very pleasant person. Even the social workers hinted ‘you don’t need to know people like that.’ “

After her biological mother died, Lital met her half-siblings three times. “I don’t know what I feel. To Hell with it,“ she says. “It’s hard, but on the other hand, I feel very close to them.”

When the time came for Porat to expand the family, and become a mother herself, the plot took an unexpected turn. Today, she is mother to Yuval Or, 25, named after a character played by Orna.

“I had a relationship that ended. He really let me down. I sought advice from a good friend, Dr. Simona Cohen regarding what to do now I was nearing 40 with no knight in shining armor in sight – and I wanted a child. Simona said the most amazing thing: "Talk to Yigal” – her husband. I wondered why I should talk to him. What could he possibly tell me? Yigal suggested we should all make a child together.”

You, your best friend, and her husband?

“We brought a child into the world out of choice and with a huge amount of love. She’s an amazing girl. Orna was a wonderful grandmother. They had their own games and their own moments when only they knew what was so funny.

At first, my mother was a bit concerned about how all of this would play out. She said to me: ‘It’s not normal. It’s a can of worms.’ But a minute later, she became Yigal’s best friend. She joined us on trips with Yigal and Simona. She and Yigal would climb together to the top of the mountain in some forest and they’d come back with a quiet kind of mutual understanding.

Words can’t explain this kind of connection. A connection of two people, neither of whom likes talking but likes sitting together with a bottle of wine. They were good times. It wasn’t a regular family, but it really is very normal. I must pay tribute to Simona’s huge heart and great friendship. She knew Yigal wanted more children. That hadn’t worked out for them. Then I show up for advice and she understood that what was good for me, was also good for Yigal. Her offer was so generous. I felt a bit strait-laced about it. It was hard for me to accept at first. Eventually, they both said: ‘This is what you want. What’s the problem? Let’s get to work'.“

One fine legacy

And there were some particularly challenging times. Orna Porat suffered mental breakdowns no less than three times in her lifetime, ending up in Geha Psychiatric Hospital. “There were always two Orna’s in me,” she said in a 2000 interview in which she spoke openly about her split personality that led to her hospitalization.

“It comes on suddenly and it’s very deep,” she told journalist, Amira Lam. “I felt something strange. I knew I needed help. I kept telling people at the children’s theater offices. I felt I wasn’t okay. My late good friend, Ada Ben-Nachum who worked with me, was the only one who really understood what was going on. She helped me make decisions – there were days I couldn’t concentrate. I’d focus on the tiny details. I couldn’t sleep. On the one hand, I was thinking very sharply, on the other hand – I wasn’t in control. I felt my mind was becoming warped. But no one wanted to believe me. People just kept saying ‘Orna Porat? Stupid? That can’t be'.”

“At first, I thought I had a brain tumor. It had been five years since my cancer. I went to see the doctor who‘d treated me and I said to her; ‘I’m beginning to go mad. Help me. Put me in hospital, where I can sleep somewhere safe'.“

"Without her, we wouldn’t have the children’s theater that has attracted so many children and young people. Her theater educates the values by which she lived. And that’s one fine legacy. She wanted to create a theater that would let children develop their imaginations and sense of judgment and that would encourage free thought"

“She called a psychiatrist to check me. I answered all her questions reasonably, because one Orna is always sharp as a knife and the other Orna was losing control. I begged them to keep me there. I felt it was dangerous for me, but they refused. Ada brought me home and my dog tried attacking her because he saw I wasn’t okay. I was in enormous distress. I lost control.“

Lital explains that “what was guiding her was the right thing and complete purpose. She fought for these things all the time. She would never play ball with how people used to think – that you should conceal this kind of thing. That’s why she gave interviews about it. She just said ‘Sorry, that’s not right. It’s like a person has a broken leg, or some kind of illness. It’s just that your soul is hurting, so why shouldn’t we talk about it? I really don’t understand the idea of being embarrassed about these things? Why should you be embarrassed about suffering for which you’re not responsible?’”

In later years, did she talk about the end drawing near?

“I don’t think she was very interested in it. In some ways, she was like an animal. She accepted reality in a very simple, basic and healthy way. She was tired of life and she said to me ‘Why do I need to live like this? What have I done? She died at home, not in hospital. I wouldn’t let her die in hospital. She also had a wonderful carer.“

What would your mother say about the theater today?

“She’d love it, but she’d have her criticism. Without her, we wouldn’t have the children’s theater that has attracted so many children and young people. Her theater educates the values by which she lived. And that’s one fine legacy. She wanted to create a theater that would let children develop their imaginations and sense of judgment and that would encourage free thought. She mortgaged our home to make it happen. She took it a bit too far. We almost lost our home. Eventually, the Education Ministry covered the debts. I can’t imagine any government ministry bailing us out today.”