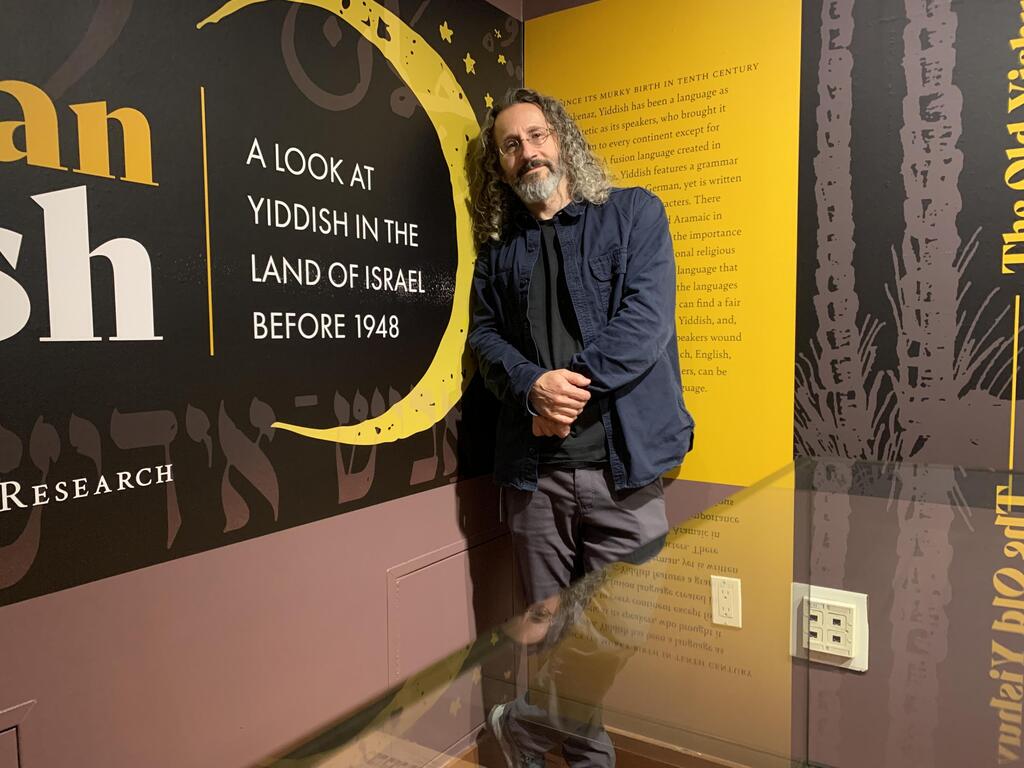

It's hard to say that Dr. Eddy Portnoy, the chief curator of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, shies away from controversy. After all, this is the institution that brought you the exhibition Am Yisrael High: The Story of Jews and Cannabis, and another on Jewish wrestlers, reminding us that we too once had our versions of 300-kilogram sumo fighters, like Martin "Blimp" Levy. However, the current exhibition that Dr. Portnoy has curated at the institute in Manhattan is, surprisingly, perhaps the most provocative of all.

Read more:

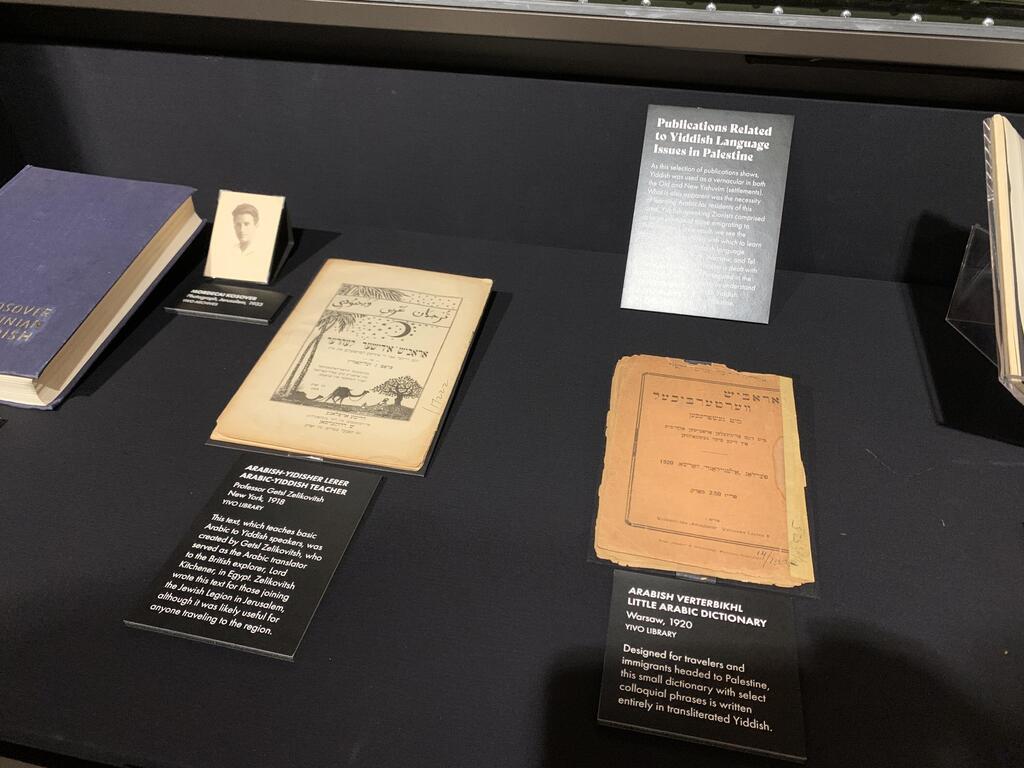

In the exhibition Palestinian Yiddish: A Look at Yiddish in the Land of Israel Before 1948, which opened this week at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, he is actually exploring for the first time how the most popular language among world Jews in the past disappeared from the Israeli landscape.

Who, in fact, killed it? There was a time when every second Jew in the world spoke Yiddish. While it has commonly been thought that the Nazis were the ones who led to the destruction of the "Jewish language," the new exhibition shows that, in this regard at least, Hitler had accomplices. The Nazis started the work, but ironically, it was the early Israelis, the Zionists, who helped them finish off the language.

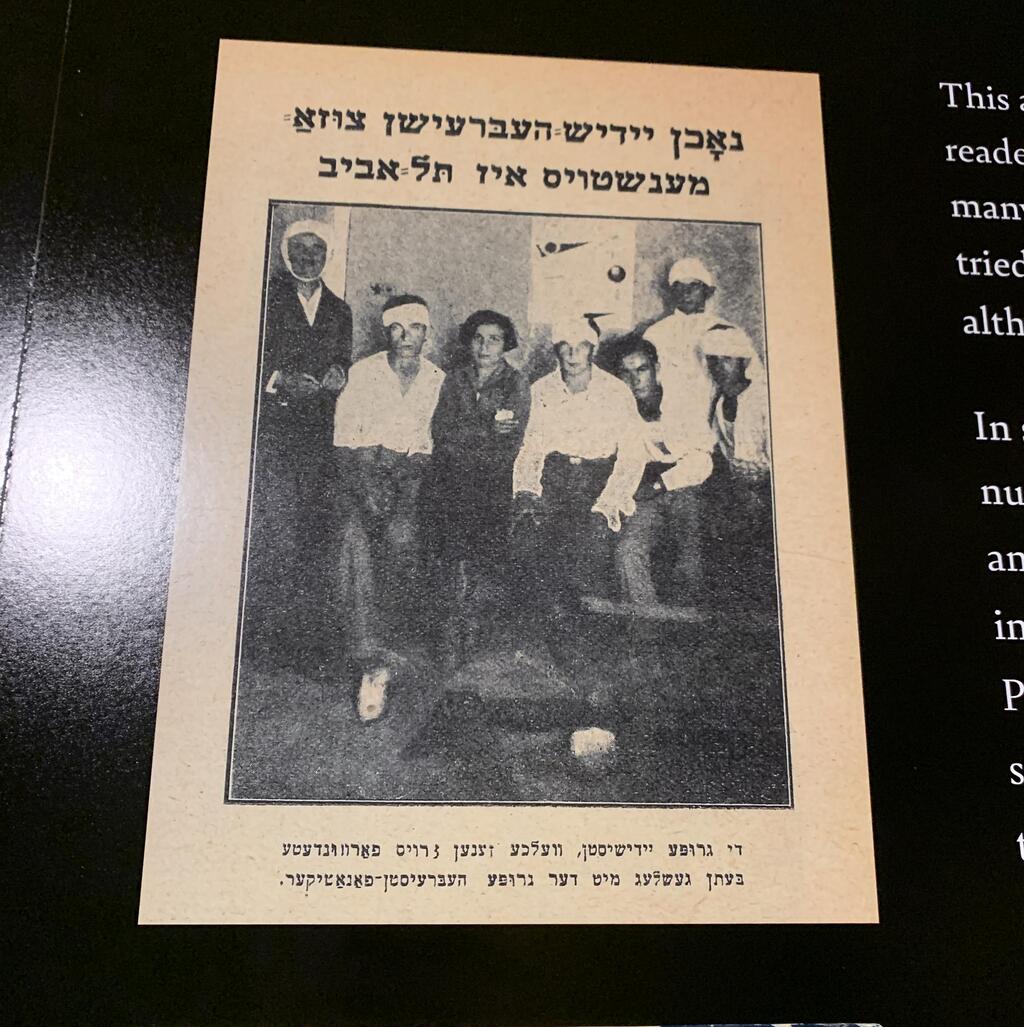

One of the central exhibits in this modest yet fascinating exhibition, which will be on display here over the coming fall months, is a black-and-white photo from 1928. The image shows a familiar sight of young people who are wounded and bandaged, seemingly as a result of another pogrom against Jews. However, in this case, the attackers were not antisemites or Palestinian Arabs, but Jews themselves. The young people in the photo were beaten in broad daylight on the streets of Tel Aviv by other Zionists because they dared to speak Yiddish publicly.

This photograph was published in a Jewish weekly in Warsaw and eventually found its way into the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, which focuses on the history and culture of East European Jewry and is today considered the largest of its kind in the world.

In other words, it serves as material in the hands of the curator, Dr. Portnoy, who continually unearths gems for surprising exhibitions about a culture that is slowly disappearing from the world.

He says those who come to the exhibition will see a “culture that revolts against the culture it came from and ultimately suppresses it so much and weakens it so much that it practically disappears.”

“Who else wanted to destroy Yiddish? Antisemites. Obviously, there's no connection between Zionists and Nazis. But they're both guilty of suppressing Yiddish in very different ways,” he adds.

11 View gallery

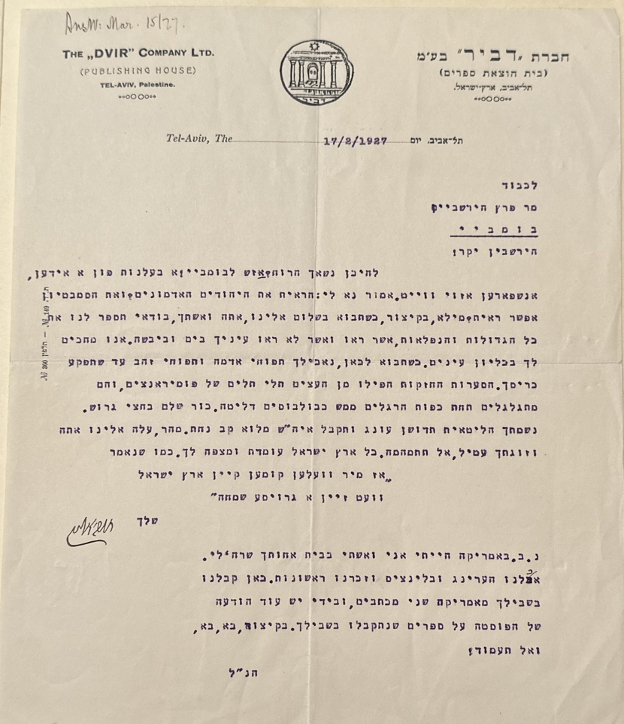

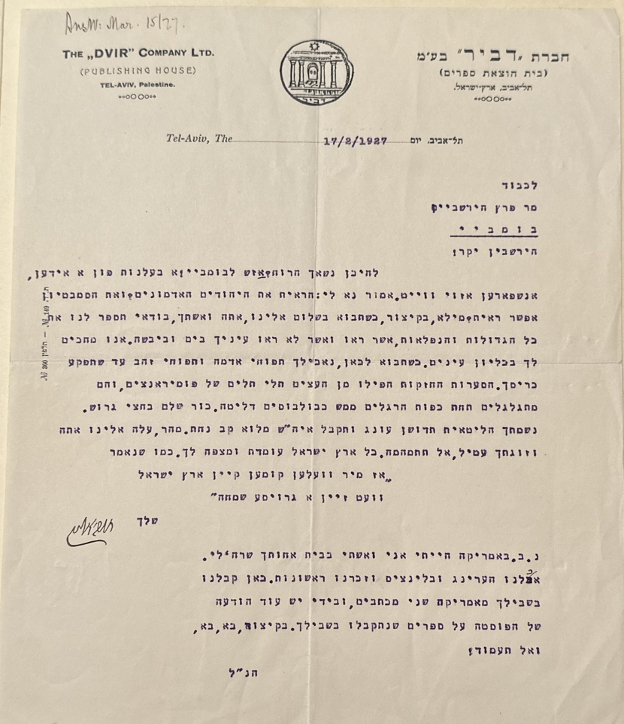

A 1925 letter from Haim Nachman Bialik to his longtime friend, the playwright and journalist Peretz Hirshbein, who was traveling with his wife in India at the time

(Photo: Courtesy of YIVO)

Dr. Portnoy is aware that this is a controversial and extraordinary statement, “But it's a very unusual thing to say, but I think it's very strange that the most successful Jewish political movement of the 20th century helped to destroy the most spoken language of the Jews during the same period.”

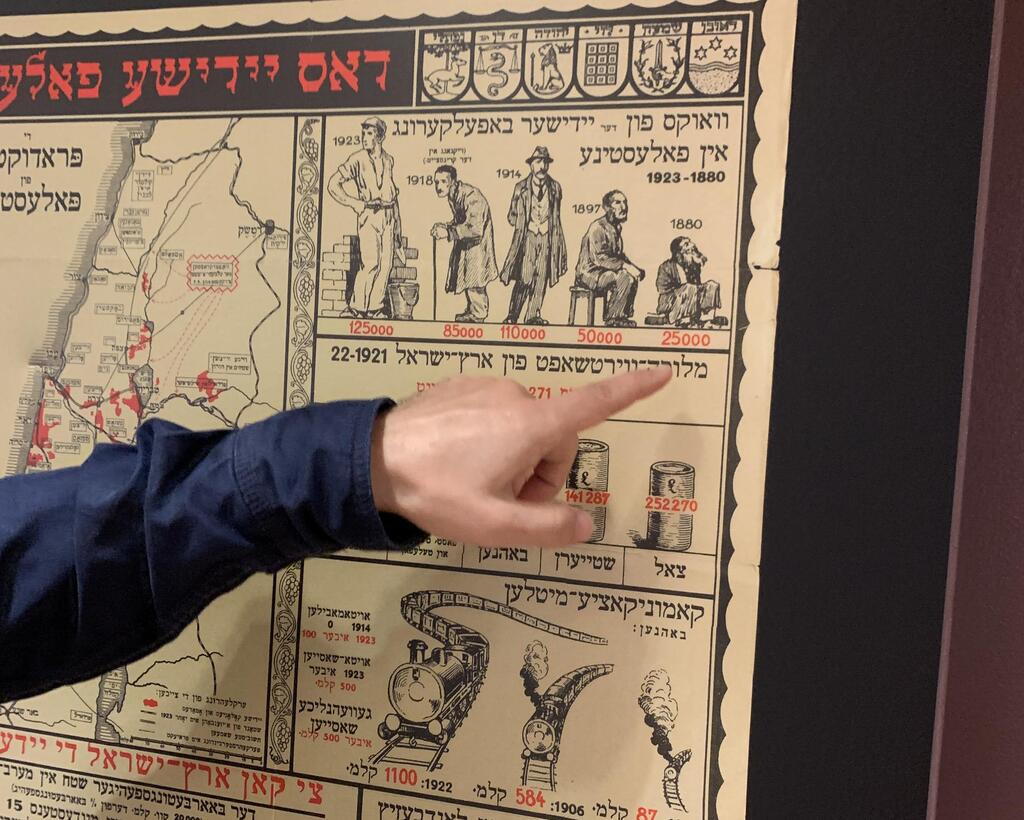

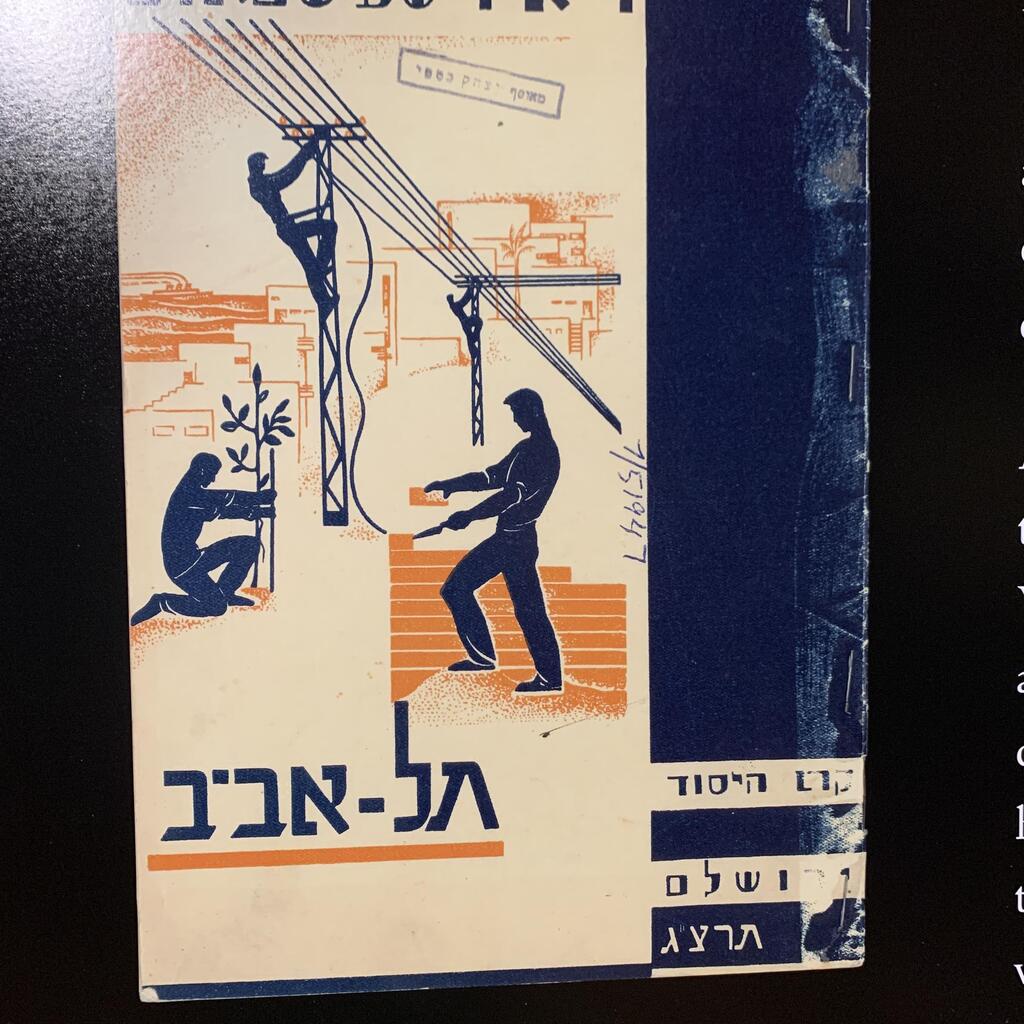

Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are greeted by a chilling Zionist propaganda poster from 1923 that parodies the March of Progress—the famous illustration by Rudolf Zallinger that depicts human evolution from ape through a procession of human figures at various stages.

However, in this version, instead of the ape, there is a stooped Yiddish speaker using a walking stick, who "evolves" ultimately into a muscular Zionist, a construction worker in laborer's clothes. This reflects the same "Muscular Judaism" ideology promoted by Zionist leaders like Chaim Bograshov, one of the founders of the Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium. In 1914, he even encouraged his students to act as human shields for the building of the lecture by Chaim Zhitlowsky, the central proponent at that time for the preservation of Yiddish culture.

Zhitlowsky had come to Israel that year partly to deliver a lecture at the school about Yiddish. However, some of the students from the gymnasium—which was then considered the most important center of Hebrew culture, producing the new elite generation of Hebrew speakers—disliked the idea and tried to persuade him to cancel the lecture. After Zhitlowsky insisted on going ahead, the decision was made, encouraged by the school's head Bograshov, to forcibly prevent the lecture. At the height of the conflict, a gun was even drawn and a shot fired into the air. The commotion later subsided that night—but this was just the beginning.

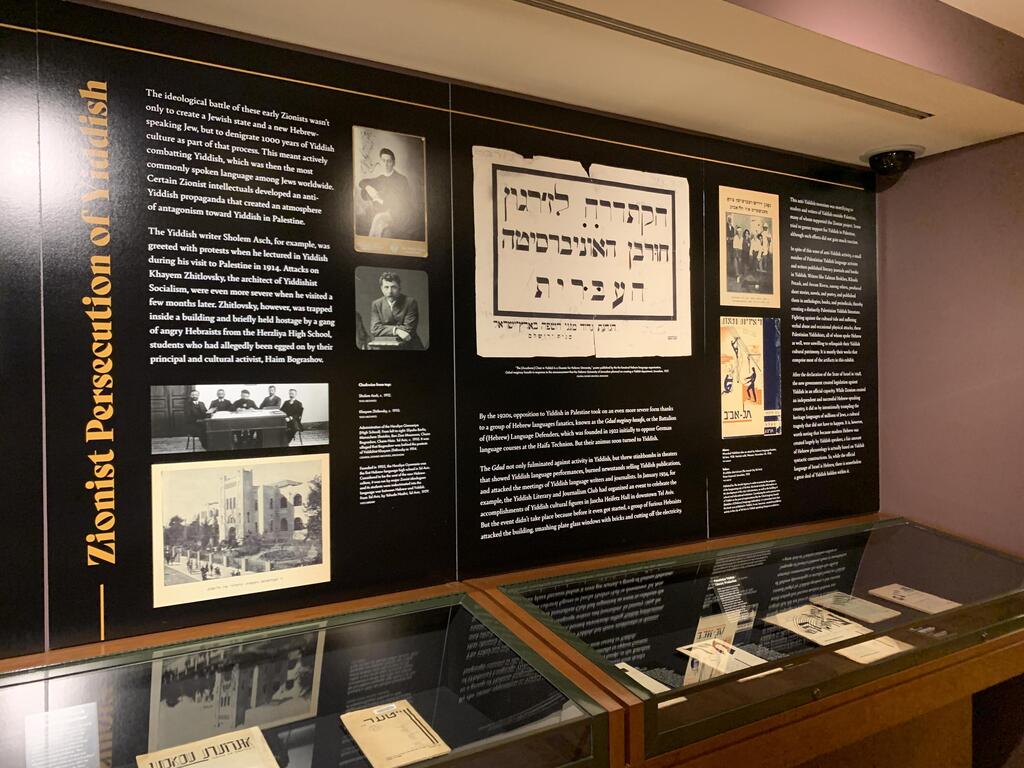

In the 1930s, movie theaters in Israel tried to screen films in Yiddish, but opponents of the language would agitate outside the establishments, interrupting the films, throwing smoke bombs and stink bombs into the screening rooms. They would also set fire to newspaper stands that sold Yiddish newspapers. The exhibition also describes an event from 1934 in Tel Aviv where Hebrew Warriors arrived at a meeting of the Association of Yiddish Writers and Journalists, smashed the windows and cut off the electricity.

“It's just a language, why get so excited that you're willing to commit violence in the name of one Jewish language against another Jewish language," Dr. Portnoy says. "And interestingly, they didn't do this to other Jewish languages. They didn’t do it to Ladino. They never bothered with the people who spoke Arabic, it was not a problem. But for Yiddish specifically, it was just this whole concept of shlilat ha'galut (negation of the Diaspora) which is heavily focused on Yiddish and Yiddish culture.”

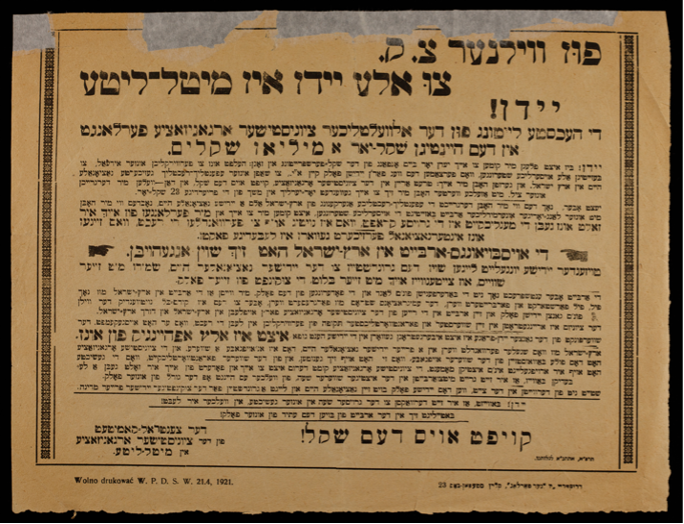

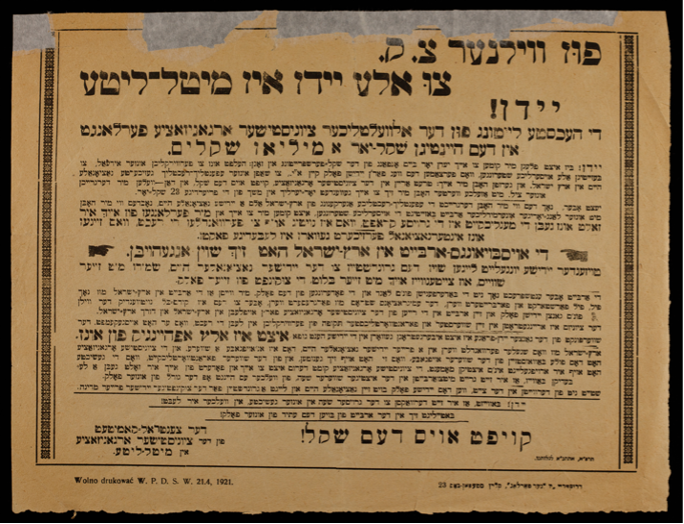

11 View gallery

Zionist propaganda poster in Yiddish from Lithuania, 1921, calling on Jews to join the movement: 'Join the work of building the future of our people!'

(Photo: Courtesy of YIVO)

According to Dr. Portnoy, any such attack on traditional Eastern European Jewish culture was not just aimed at the ultra-Orthodox or Hasidic communities, but at anyone who spoke the language. So much so that during the British Mandate period, there was a Zionist law stating that if you had lived in the land for more than two years, you were forbidden from speaking publicly in any language other than Hebrew. Anyone who violated this would end up beaten and bandaged, as evidenced by the photos of the wounded in the 1928 newspaper.

And this campaign was quite successful. By 1939, before World War II, Yiddish was the most spoken language among Jews worldwide. Around 10 million Jews used it as their everyday language.

"In Europe, it was wiped out by the Holocaust. In the United States, it’s destroyed by assimilation. In Israel, it's destroyed by mostly cultural and physical needs," he says.

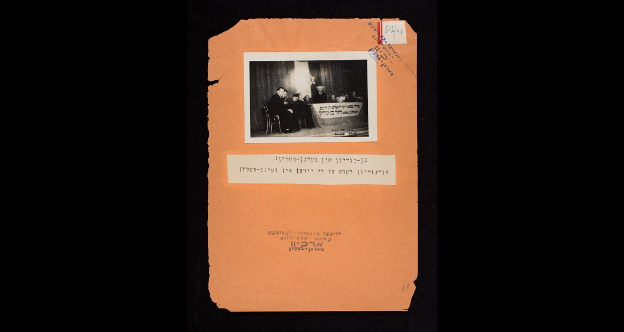

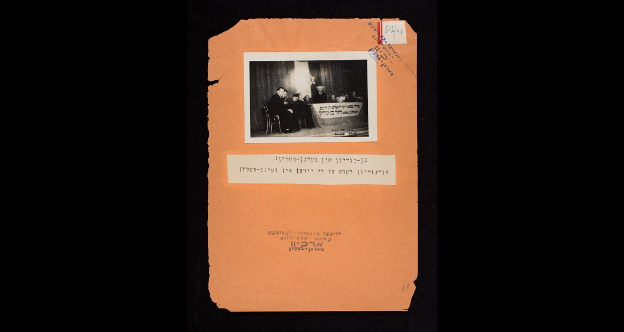

11 View gallery

A rare photo of David Ben-Gurion visiting the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945; Above the podium where he spoke was written in Yiddish: ‘We welcome our distinguished guest, David Ben-Gurion’

(Photo: Courtesy of YIVO)

The roots of this deep-seated animosity toward Yiddish and the negation of the Diaspora can ironically be found in the Diaspora itself, long before it was imported into Eretz Israel. The negative attitude toward Yiddish actually begins with the historical enlightenment movement, which sought to modernize traditional Judaism and integrate it into European culture. The leaders of this movement were strongly opposed to Yiddish, not seeing it as a legitimate language but rather as a kind of "complex jargon."

In fact, when the first Hebrew newspaper was launched in the Russian Empire in 1862, which of course was published in Yiddish and quickly became a sensational success, it triumphantly stated that "Yiddish is not a real language, and one cannot think intelligent thoughts in it."

“This is what they write in the Yiddish paper,” Dr. Portnoy says. “It's incredibly ironic.” Zionist propaganda posters that were later distributed in Israel and are displayed in the exhibition don't even refer to the language as Yiddish. Instead, they call it a "jargon" and according to Dr. Portnoy, ”it's like some of the Arab countries won't say Israel, they say the Zionist entity. So the early Zionists wouldn't say Yiddish, they would call it something else. It was the same sort of extremism.”

The negative attitude toward Yiddish among Jewish intellectuals in the Diaspora was highly influential and later permeated the Zionist movement as well. According to Dr. Portnoy, “It's because the social and political position of the Jews was very low. They are completely oppressed. And people associated this oppression with the culture. And because language is the carrier of culture. This was the this became their attitude toward Yiddish.”

So this is like internal antisemitism?

“It's Jewish self-hatred is what it is. For the most part, many of the socialist scientists like Poale Zion (a Marxist Zionist movement) actually supported Yiddish quite actively. They were really the only group that did. And they did it because they understood that Yiddish was the language of the Jewish proletariat, the Jewish working class, and it also because they wanted to maintain good relations with Jews in the Diaspora, the majority of them spoke Yiddish.

So it was very utilitarian. Most Zionists wanted a modern Hebrew, and they promoted and developed it and they also develop this idea of muscular Judaism in opposition to the image of Eastern European Jews, who were weak and poor, and disenfranchised and spoke Yiddish. So all of this together became this whole sort of sphere of negativity, and so it was just sort of thrown out.

Dr. Portnoy describes it as quite ironic, considering that most Jews who arrived in Palestine during the First and Second Aliyah were Yiddish speakers. For example, Ben-Gurion's first language was famously Yiddish, but he and other early Zionists learned to despise it. There's the famous quote from Ben-Gurion during a conversation he had after the war with a concentration camp survivor. While she was speaking, Ben-Gurion said to her and those around her: “I hate the sound of this language.” She was speaking Yiddish.

"The idea that you can't have both, Hebrew and Yiddish. It doesn't make sense that you couldn't. But in any case, Zionism was a revolution. And revolutions have victims. And one of these victims was Yiddish," Portnoy says.

However, the exhibition also describes better times when Yiddish flourished in Israel. The display opens with what is likely the earliest evidence that the language was in use in Palestine for centuries: part of a letter found in the Cairo Geniza from 1560, signed by a woman living in Jerusalem who corresponded in Yiddish with her son living in Cairo.

By the end of the 18th century, a wave of Yiddish-speaking Hasidim arrived in the Holy Land, and not long after, they were joined by Yiddish-speaking Lithuanians. Together, they significantly increased the number of Yiddish speakers in the old Yishuv, alongside other spoken languages like Arabic and Ladino from Sephardic Jews. The exhibition showcases ten examples of how Arabic was integrated into Yiddish at the time, and according to Dr. Portnoy, this is one of the beautiful features of the language.

“It's a very flexible language that easily absorbs words and phrases from other languages. So in American Yiddish, you have a lot of English words and in Polish Yiddish you have a lot of Polish words and Yiddish in Argentina, you have Spanish. In Israel, there's a lot of modern Hebrew, which didn't exist before,” he says.

In 1908, a small Yiddish newspaper was already being published in Palestine by Poale Zion, and more and more Yiddish manuscripts from that period can be found, including various poems, stories and novels that are displayed in the exhibition.

“They wanted to write stories and novels in Yiddish. This was their mother tongue. It was a language they loved. And they wanted to produce cultural materials in it. And so they created all kinds of magazines and different kinds of publications in Yiddish. Some of them are literary, some of them are political,” Dr. Portnoy says.

Is there a way to make amends for the past? In recent years, Yiddish has enjoyed a certain renaissance, primarily due to its use among the growing ultra-Orthodox population. Despite this, the numbers don't come close to the language's "golden era."

“Yiddish is not extinct. You have small numbers of people who support these things. In theory, the government should support it,” Portnoy says. “There's a lot of activity in Yiddish in Sweden. One of the reasons is because it was declared by the government to be a national minority language. And so they give it government funding, not a lot, but enough to do things.

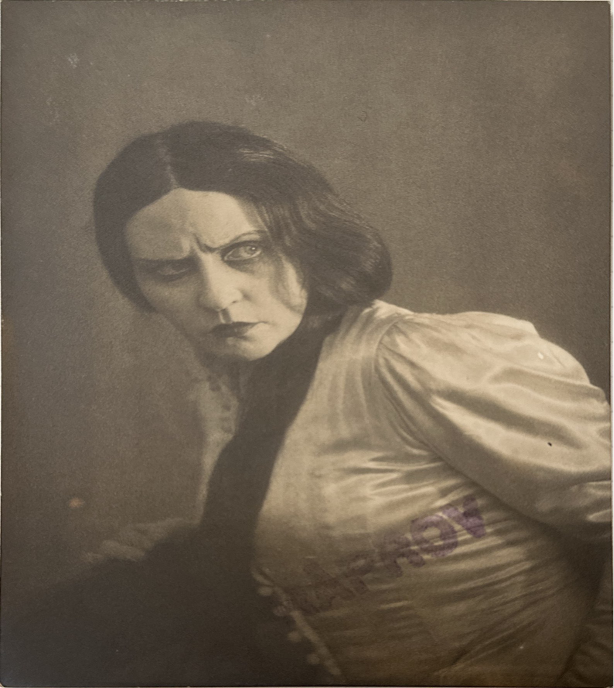

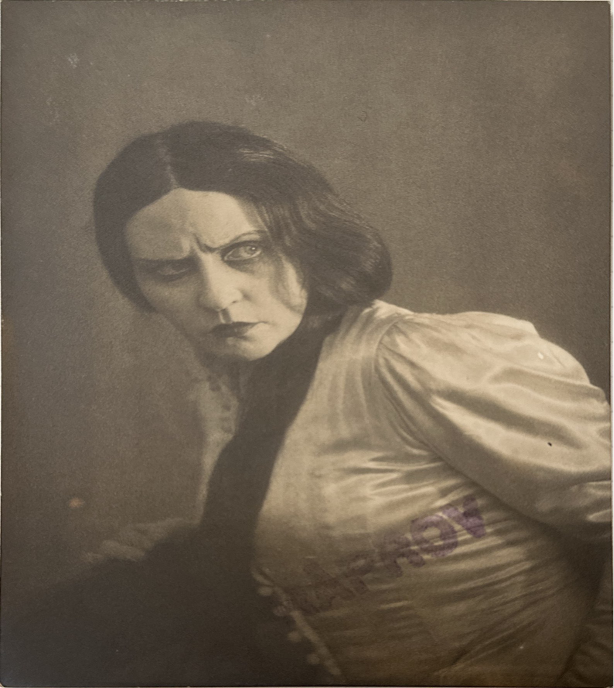

11 View gallery

Pictured is Robina playing her most famous role as Leah in The Dybbuk in Sweden, 1938; YIVO recently acquired a large collection of materials about the ‘First Lady of Hebrew Theater' which follow her life and her transformation into a Hebrew cultural icon

(Photo: Courtesy of YIVO)

“I remember when I was in Israel in 1989 and I went and saw a huge Yiddish show in Ramat Gan in this very small theater. It was probably like 200 people or something and it was all old people.”

The current exhibition is just one of many treasures hidden in the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, which focuses on the history and culture of East European Jewry. Founded in 1925 in Vilna, the institution was then considered the Yiddish counterpart to the Hebrew Language Academy and was essentially the governing body for dictionaries and language standards in Yiddish.

Today, the institute, which relocated to New York to escape the Nazis, no longer engages in coining new words or convening to decide on language norms. Instead, it focuses on the research and promotion of Ashkenazi Jewry and operates almost entirely in English.

Its archive contains over 24 million manuscripts and texts—primarily in Yiddish, but not exclusively—making it the largest archive of its kind in the world.