Four generations after the Holocaust, members of Generation Z are coming of age at a time of increasing anti-Semitism and are vulnerable to online influence more than ever, according to speakers taking part in a virtual conference, discussing ways to combat hatred of Jews around the world.

The September 8-10 online gathering - called “Shaping Future Discourse about Racism, Anti-Semitism & Hate Speech" - was hosted by Startup Media Tel Aviv, an initiative promoting proper news coverage of Israel and Jewish matters.

Members of Generation Z, defined by the Pew Research Center in 2019 as those born in 1997 or later, have grown up online and are thus particularly susceptible to Jew-hatred. Yet according the speakers at the online conference, the platforms used to spread anti-Semitism can also be used to combat such biases and to educate people.

As a starting point, speakers advocated that online platforms adopt the “Working Definition of Anti-Semitism,” formulated in 2016 by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance [IHRA].

According to the IHRA, “anti-Semitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.”

With a clear definition and public commitment to fight hate speech, the social-media giants might be more likely to remove anti-Semitic statements, speakers said.

Emily Schrader, a researcher of online hate speech concerning women’s rights and anti-Semitism at the Tel Aviv Institute, told The Media Line: “We must collaborate with the social-media networks to push forward a working definition of anti-Semitism such as IHRA’s that will address the unique manifestations of anti-Semitism prevalent on social media today.”

One way to do so, she says, is by using the same platforms “to monitor anti-Semitism and educate and call out anti-Semitism whenever it is present. When anti-Semitism is threatening or violent, it should be removed outright, and potentially the users posting the content [should be] as well.”

Schrader is also CEO of the Social Lite Creative digital-marketing agency.

“Gen Z needs to understand that just because you can say something on social media doesn’t mean you should. The networks play a key role in this,” she said.

However, definitions are of limited use, according to Christina Hainzl, who heads the Research Lab on Democracy and Society in Transition at Danube University Krems in Austria. “It’s nearly impossible to have one definition that covers all anti-Semitism because there are always in-between cases,” she said.

“What we see in Austria and in some ways all over Europe is that many Jews don’t want people to know they are Jewish. If you ask how they perceive anti-Semitism in Austria, they very often answer that they do not have a problem with it, but they also don’t talk much about it because they’re afraid of repercussions,” Hainzl said.

”This avoidance behavior is quite significant in Austria because it restricts the lives of Jews,” she said, “yet it is not covered by IHRA and would still be difficult to include in a working definition of anti-Semitism.”

IHRA provides 11 examples of anti-Semitism. Four involve Israel, such as holding it to a double standard by expecting it to conduct itself in a way that is above and beyond what any other democratic nation might do, and holding Jews collectively responsible for the State of Israel’s actions.

Yedioth Ahronoth journalist Ben-Dror Yemini said during the conference that there was a difference between legitimate and anti-Semitic criticism of Israel.

“Criticism of Israeli policy is totally legitimate; we [Israelis] do it all the time… even about Palestinians and the settlements,” Yemini said. “What is not legitimate is lies and deception.”

Lukas Mandl, a member of the European Parliament and head of the Transatlantic Friends of Israel group, told The Media Line: “Anti-Semitism isn’t an opinion; anti-Semitism is a crime…. Anti-Zionism is one kind of anti-Semitism.”

Another IHRA example of anti-Semitism is denying Jews the right to self-determination and claiming that the State of Israel is a racist endeavor.

But the matter of defining anti-Semitism has spurred controversy.

“There is a lot of debate and criticism” over the inclusion of anti-Israel sentiment, Dr. Dina Porat, head of Tel Aviv University’s Kantor Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry, said.

According to Schrader, some online platforms apparently have more of an anti-Semitism problem than others.

“Twitter is the worst of the mainstream social-media platforms. There is a high number of white supremacists and Nazis, as well as Islamic extremists and generally hateful comments. [It has] also been trailing behind other platforms in removing or labeling posts that are blatantly hateful,” she said.

“After Twitter, TikTok is struggling the most to effectively combat anti-Semitism on its platform though [its] terms of use are generally more stringent than Twitter’s,” she added.

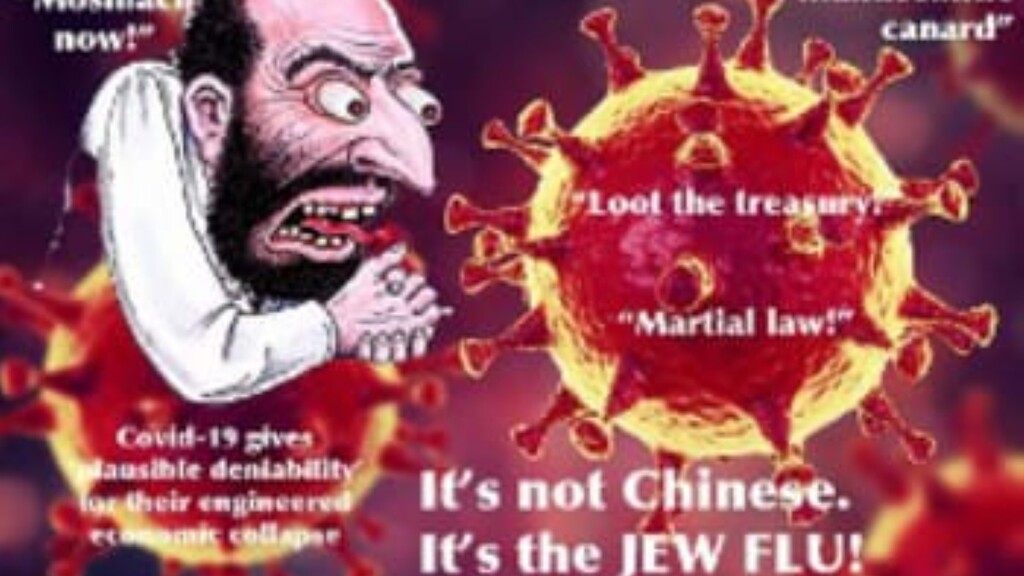

Schrader also provides examples of online anti-Semitism.

“There’s classical anti-Semitism, such as the tweet from April which stated ‘Jews invented coronavirus,’ and there is modern anti-Semitism, such as when a user posted a photo of an Israeli flag on Facebook with a swastika replacing the Star of David,” she said.

“The major social-media platforms have repeatedly failed to adequately deal with both, though they have been better about when the word ‘Jew’ is used [instead of] ‘Zionist’ or a reference to Israel,” she continued. “Incidentally, this does not apply in Arabic [postings], where they have failed in both.”

Some say that the ability to stop online anti-Semitism is limited.

“[This bigotry] is something that has always existed and will continue to exist,” Barak Shachnovitz, CEO of TwoHeads marketing, said.

Rabbi Dov Lipman, a former Knesset member, told conference-goers it is difficult to change anti-Semites although action must be taken to prevent others from adopting their ideology.

“We can’t change people but we can take [their message] down to prevent its spread to new people,” said Lipman, in charge of community outreach for Honest Reporting, which defends Israel from media bias.

“It’s hard to debunk, but most people… say that racism is wrong,” he stated. “You have to show that anti-Semitism is racism.”

Social media is also used by Holocaust deniers but can in turn be used to fight them. A recent example includes the story of Eva, a Jewish girl who lived during the Holocaust, told over Instagram.

“Those who experienced the Holocaust are dying. We have to spend time with them and gather their memories in a way that is accessible to the younger generation,” Ksenia Svetlova, a former Israeli politician and currently a senior fellow at the Mitvim Institute for Foreign Policy, told attendees.

“We have to do our utmost to be innovative while we still have people who can tell their story,” she stated, calling for more efforts on social media.“In some cases, this form may have more influence than the traditional Holocaust [education] format,” Svetlova added.

Alana Baranov, a steering committee member of the World Jewish Congress’ Jewish Diplomatic Corps, agrees.“We have to meet young people where they are, use apps [and] other digital tools,” she told the conference. “This awareness [then] needs to translate into concrete action. It has to make youth proactive.”

The article is written by Tara Kavaler. Reprinted with permission from The Media Line