For two hours every day, Lee Si-young and her colleagues broadcast uncensored foreign news into closed-off North Korea, with a cruel and unthinkable awareness: If their listeners are caught tuning in to her station, they are sent to prison.

Free North Korea Radio has been broadcasting from the South Korean capital, Seoul, for two decades. During that time, it has tried to push real-time news into the communist country ruled by Kim Jong Un, and before him Kim Jong Il, in an effort to crack, even slightly, the walls that hide the outside world from its 26 million residents.

But Lee says she now feels a real crisis. Funding cuts and policy shifts by the governments of the United States and South Korea have led to the shutdown of broadcasts that until now were backed by government money. “Our frustration is huge, and we are afraid they have abandoned the people of North Korea,” says Lee, a defector from the North who runs the station.

In North Korea, all radio and television sets are locked to state channels, the regime’s channels. But defectors who managed to escape say they used to modify their receivers or rely on smuggled devices to listen in secret at night to foreign broadcasts, exposing themselves to information the regime does not want them to hear.

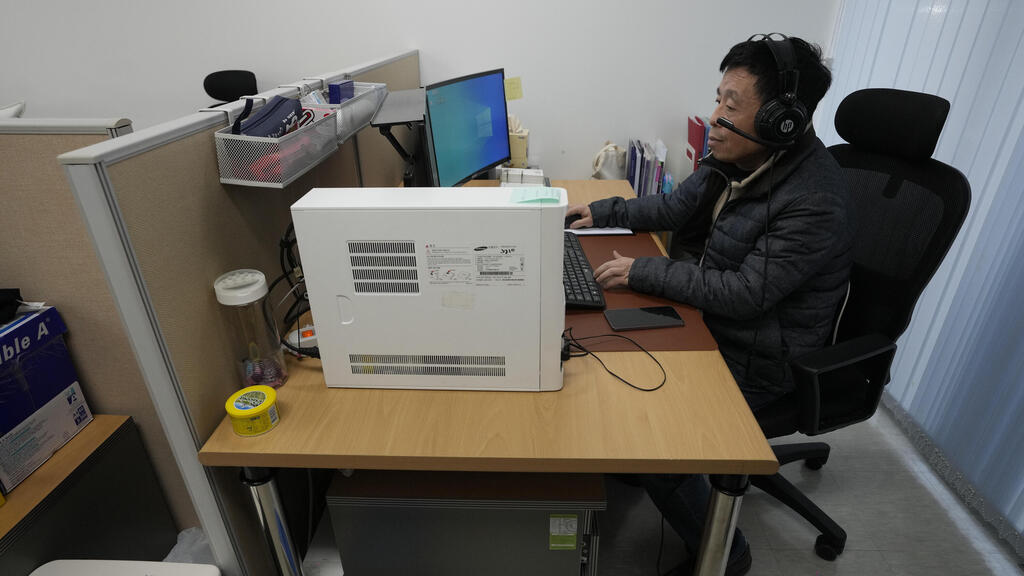

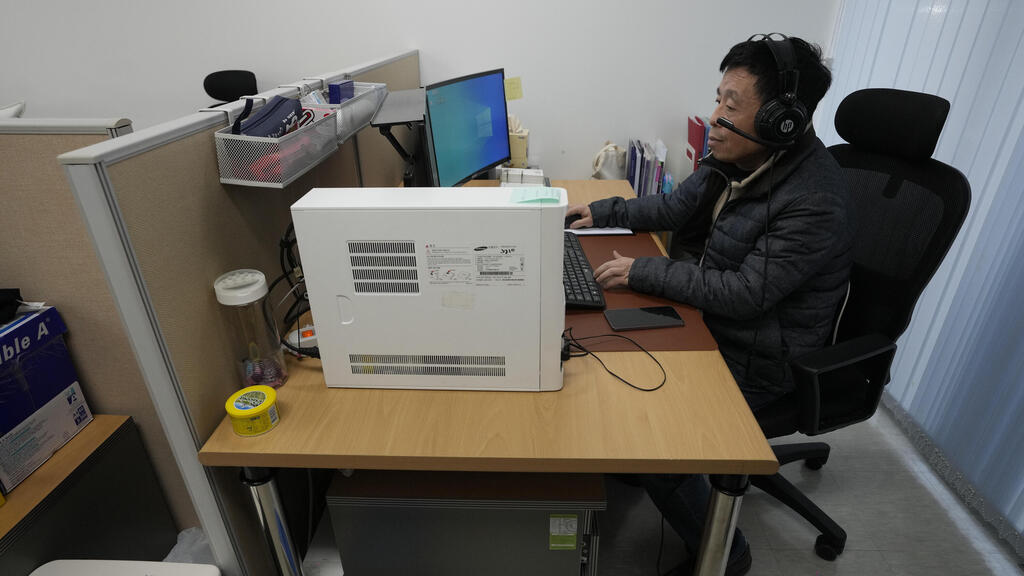

5 View gallery

Lee Si-young, director of Free North Korea Radio; 'The frustration is huge'

(Photo: AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Those reports include outside coverage of the Kim dynasty that has ruled the dictatorship since its founding, glimpses of a richer and freer Western lifestyle, and success stories of defectors who fled North Korea and built better lives abroad.

The recent moves by Washington and Seoul now threaten that important project. The website 38 North, a respected outlet covering developments inside North Korea, estimated last month that such radio broadcasts have shrunk by 85% because of the cuts.

Two major stations that operated for years with US government support, Voice of America and Radio Free Asia, were forced to halt their Korean-language broadcasts after Donald Trump signed an executive order in March effectively dismantling the agency that supervised them and funded networks like theirs. Trump argued the networks leaned unfairly liberal and that investing in them was a waste of money.

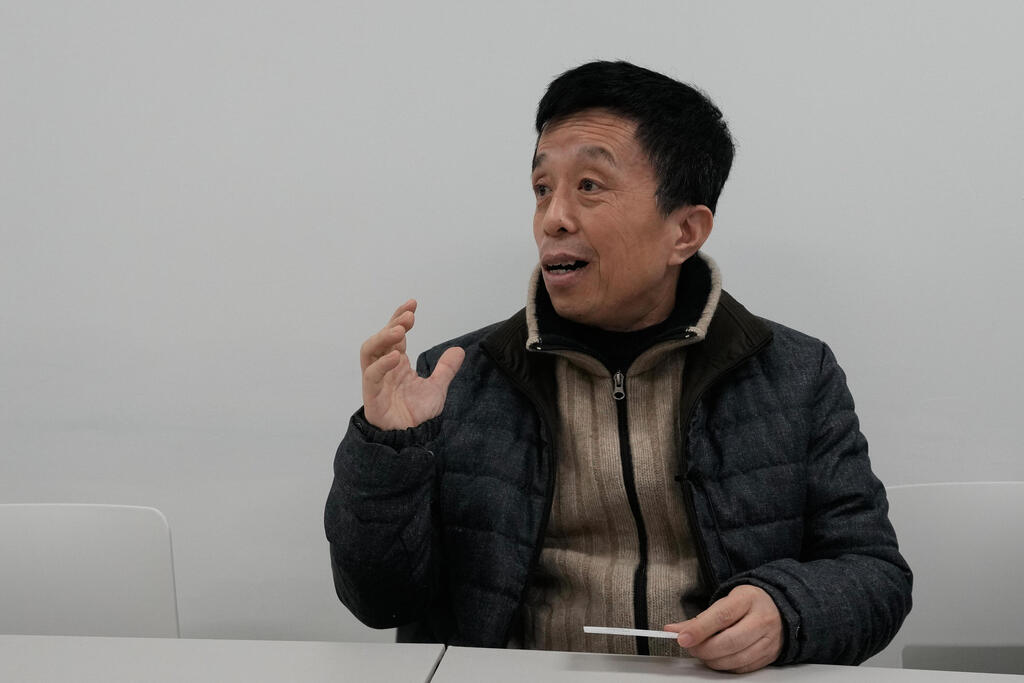

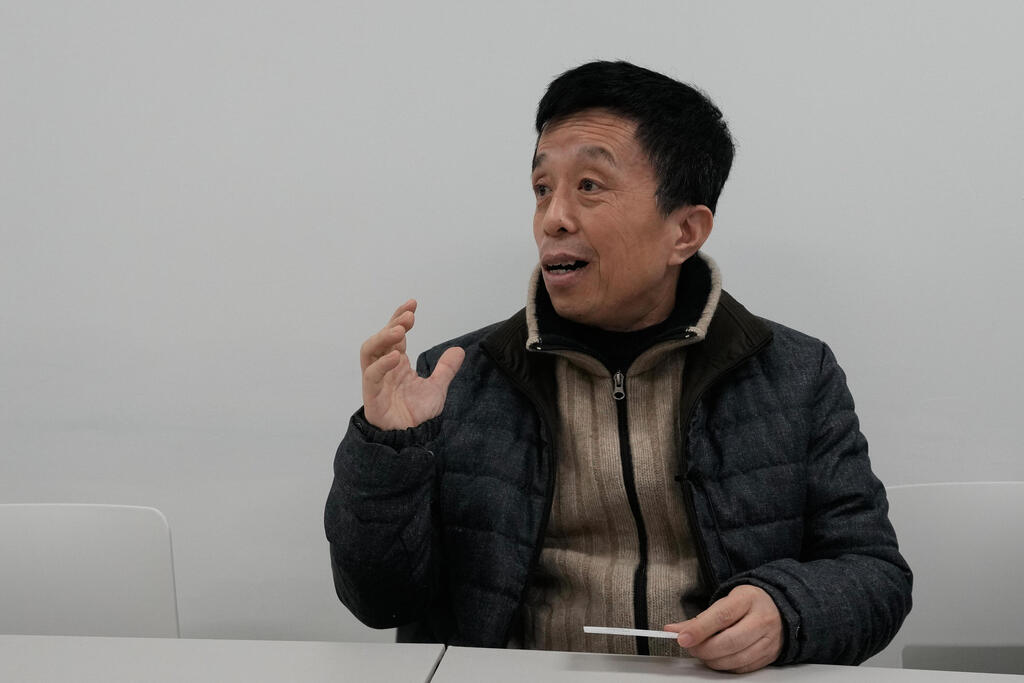

5 View gallery

Kim Ki-sung, who was stunned to hear that South Korea had given loans to the Soviet Union

(Photo: Ahn Young-joon/ AP)

South Korea’s liberal government, led by President Lee Jae-myung, also stopped its own radio broadcasts in an attempt to reduce hostile actions toward the regime in Pyongyang. As part of a broader move, Seoul has also begun preventing anti-Kim activists from setting up loudspeakers near the border to blast K-pop and world news into the North. It ordered them to stop floating balloons carrying leaflets and USB devices across the border, which were meant to reach North Koreans and expose them to what is happening beyond their country.

Free North Korea Radio is now one of the last small civilian or religious groups still broadcasting into North Korea. Lee says Voice of America and Radio Free Asia were far larger than her station, which has only five employees, all defectors from North Korea. “It hurts, and we don’t know what we should do,” she says. “Should we tell North Koreans that the suspended broadcasts were stopped only temporarily and will surely return, or update them that we are one of the few stations still surviving?”

Not to topple the regime, just to show there is a better world outside

Despite the difficulties of sending news from abroad into North Korea, Lee Yoang-hyeon, a defector who became a lawyer in South Korea, launched a website and phone app this month aimed at offering North Koreans alternative ways to access outside information.

Lee says the site and app, called Korea Internet Studio, will first target the thousands of North Koreans living abroad, outside North Korea, including foreign workers, students, diplomats and their families. Many of them have mobile phones with access to the global internet, a privilege that citizens inside isolated North Korea do not have.

5 View gallery

Up to five years in prison for anyone caught listening to unauthorized radio stations; Kim Ki-sung at the station’s offices

(Photo: Ahn Young-joon/ AP)

He says his organization aims to produce practical content that North Koreans abroad can use, such as explaining what gifts foreign workers can buy for loved ones back home or what cryptocurrency is. “We do not expect the public using our content to start an uprising and overthrow the North Korean regime,” he stresses. Instead, the goal is that North Koreans “learn there is a good world where they can enjoy certain freedoms and rights.”

Lee believes North Korea will eventually ease its tight internet restrictions cautiously, for example by allowing Chinese, Russian or Vietnamese companies to open offices there. Many experts are skeptical. Since 2020, North Korea has introduced especially harsh laws to intensify its battle against foreign cultural influence, particularly South Korean culture.

The “reactionary ideology and culture rejection law” sets penalties of up to 10 years in prison with hard labor for anyone who consumes foreign films or music, possesses them or distributes them. It also mandates up to five years in prison for consuming unauthorized radio and television broadcasts.

To keep going, even if there is only one listener

Before he defected from North Korea in 2003, Pak Yosep said he was stunned to hear on South Korean radio that protests were being held against the government in Seoul, something unimaginable in the North. Pak says that while serving as a soldier in a North Korean frontline unit, he enjoyed listening to music broadcast from South Korean loudspeakers placed across the border.

Kim Ki-sung, one of Free North Korea Radio’s employees, also says the South Korean radio broadcasts he listened to for a decade before fleeing North Korea in 1999 influenced him and convinced him to defect. He says he learned from them that South Korea was wealthy enough to extend loans to the Soviet Union and that it had so many cars it suffered traffic jams.

“I don’t know how strong addictive drugs are, but I think these broadcasts were addictive in the same way,” Kim says. “A lot of people ask us if we are sure North Koreans really listen to our programs, but I believe we have to keep doing this even if only one person hears us.”