The organization Alliance – Kol Israel Chaverim runs a project called "The Daily Sage," which highlights the wisdom of Jewish scholars through a unique website. In honor of the 7th of Adar II – the traditional Jewish date marking the birth and death of Moses, whose burial site remains unknown – the organization is encouraging a deeper exploration of the rabbis and sages who once led the Jewish community in Gaza.

4 View gallery

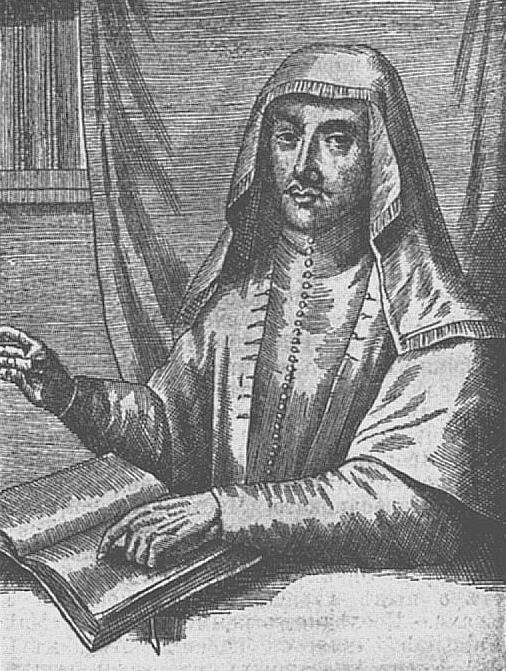

David playing the harp in a mosaic from the ancient synagogue in Gaza

(Photo: Dr. Avishai Teicher)

The 6th century: The king’s highway

As early as the 13th century BCE, when the Land of Israel was divided among the tribes, Gaza was allocated to the tribe of Judah. Yet, for a long period, the Philistines were the dominant rulers of the city.

“Even in the past, Jews were not always welcomed in Gaza, and there was often a sense of defiance in their insistence on living there,” says Rabbi Prof. Jeffrey Woolf of Bar-Ilan University's Talmud and Oral Law Department.

How far back are we talking?

“As early as the sixth century CE. Following the great Samaritan revolt, Byzantine Emperor Justinian I rebuilt Gaza and sought to exclude Jews. However, not only did Jews reside there, but they also established a magnificent synagogue, remains of which – including stunning mosaics – were uncovered after the IDF entered Gaza during Operation Iron Swords.”

Why did Jews insist on living in Gaza?

“Gaza was a crucial commercial hub in antiquity and always considered one of the most important cities in the southern region. It was located along the ‘King’s Highway,’ a major trade route connecting present-day Lebanon and Damascus with Egypt. Another route leading to Gaza originated in the Arabian Peninsula. Additionally, Gaza had a key port that facilitated extensive trade. This made the city highly contested throughout history and, because of its economic opportunities, Jews desired to live there.”

The 15th century: The rabbi from Prague

Rabbi Obadiah of Bartenura, an Italian rabbi and halachic authority, is best known for his commentary on the Mishnah. In 1486, he immigrated to the Land of Israel, documenting his journey through various Jewish communities. In 1488, he visited Gaza and spoke highly of the local rabbi.

“He did not mention the rabbi’s name,” says Woolf, “but it was likely Rabbi Moses of Prague. Though little is known about him, the fact that a rabbi left Prague’s vibrant and prominent Jewish community to move to Gaza indicates that Gaza had a significant, wealthy Jewish community capable of attracting a distinguished scholar.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Rabbi Jacob Berab, a leading Jewish scholar of 16th-century Israel and mentor to Rabbi Yosef Karo (author of the Shulchan Aruch), also noted Gaza’s importance. He described its rabbinic court as being on par with Jerusalem’s.

The 16th century: Rabbi Israel Najara

The rabbi who truly put Gaza on the map was Rabbi Israel Najara. Born in Safed in 1555 to a family of Sephardic exiles, Najara became a highly respected halachic authority.

“He was deeply revered as a halachic scholar,” says Woolf, “but also faced criticism as a poet and composer. Many people know his famous Sabbath hymn ‘Yah Ribbon Olam,’ but he wrote many others, including ‘Yoducha Rayonai’ and ‘Ya’ala Bo’i L’gani.’ He had a deeply poetic soul and was unafraid to express himself in ways that did not always sit well with his more conservative colleagues.”

In his poem for Shavuot, ‘Yarad Dodi L’Gano,’ he describes God as a groom and the Jewish people as a bride, writing: ‘My beloved descended to his garden, to beds of spice, to delight with the noble maiden.’

“This sparked fierce opposition from Rabbi Menachem di Lonzano, a prominent Italian rabbi, who accused Najara of writing as if addressing a lover rather than the Almighty.”

Despite the controversy, Najara stood his ground. He even adapted Arabic melodies into Jewish liturgical poetry, an approach that solidified his legacy. His reputation was so esteemed that the famed poet Avtalyon traveled from Turkey to Gaza to study under him. After Najara’s death, he was buried in Gaza, and his son, Moses, became a leading rabbi of the community.

The 17th century: Nathan of Gaza

Though controversial, Nathan of Gaza was one of the most influential figures in the city’s Jewish history. As the prophet of the Sabbatean movement, which proclaimed Sabbatai Zevi as the messiah, his impact was significant.

Born in Jerusalem in 1643, Nathan was not only well-versed in halacha but also a renowned Kabbalist. In 1665, he met Sabbatai Zevi.

“Scholars debate who was the dominant figure between the two,” says Woolf. “I believe Nathan was the true leader. He remained in Gaza until 1666, when Sabbatai Zevi was arrested by the Ottoman sultan and forced to choose between conversion or execution. After Zevi converted to Islam, Nathan left Gaza for Turkey.”

What happened to the Jewish community in Gaza?

“The conversion of Sabbatai Zevi was a devastating blow. But it’s important to remember that, at the time, a huge segment of the Jewish world hoped he was the messiah. Prior to his conversion, only a few openly opposed him.”

The 18th and 19th centuries: A decline in prominence

Following Sabbatai Zevi’s apostasy and Nathan of Gaza’s departure, the Jewish community suffered a significant decline. Jewish life continued, but without leading rabbinic figures. In 1799, Napoleon briefly captured Gaza, further unsettling the already weakened community.

The 20th century: The last rabbi of Gaza

Eli Barakat, CEO of Alliance – Kol Israel Chaverim, highlights Rabbi Nissim Binyamin Ohana, who was appointed Gaza’s chief rabbi in 1907 and served for five years.

He established a Hebrew-language school that taught Bible and Talmud. During his tenure, Jewish-Muslim religious relations were relatively cordial. According to Ohana, Gaza’s mufti, Sheikh Abdullah al-Alami, sought his guidance after encountering theological questions from Christian missionaries. The two met twice a week for Torah study.

When Ohana later became the chief rabbi of Haifa, he published the mufti’s theological responses –originally written in Arabic – in a book titled "Know What to Answer the Heretic."

Since Israel’s War of Independence, no Jewish community has existed in Gaza.

“There weren’t many famous rabbis in Gaza over the centuries,” Woolf acknowledges, “but that’s not what truly matters.”

What does matter?

“That is a region marked by conquests and conflicts, a Jewish community thrived in Gaza for more than 1,500 years. It had synagogues, cemeteries, religious institutions, and respected rabbis – even if most were not widely renowned.”

First published: 23:16, 02.02.25