It is another sunny morning at Rabin Square in Tel Aviv. Cafes are slowly waking up, bike lanes and crosswalks are busy, and city residents are starting another workday. Around the historic square stands an opaque, two-meter-high fence, and dozens of workers are making their way into the construction site. Above ground, it is hard to imagine what is happening below, 30 meters underground.

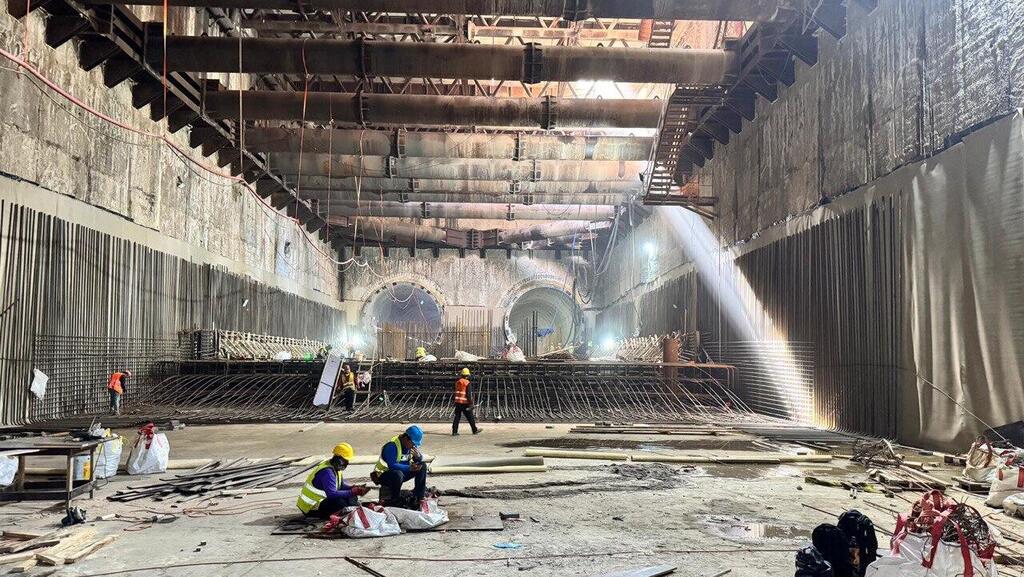

Descending carefully down temporary stairs, wearing work boots, reflective vests and helmets, we enter the darkness. After just a few meters, an entire world is revealed: two tunnels to the right and two to the left. One day, they will connect, and in four years the Green Line of the light rail will pass through here, at Rabin Square station.

Work on the Green Line has already begun to slowly reshape the streets of the Tel Aviv metropolitan area. To passersby, however, the project mostly appears as fences, temporary roadblocks and piles of dirt. Behind that surface lies one of the most complex and ambitious infrastructure projects ever undertaken in Israel, and the longest light rail line built in the country.

“Most of us travel through stations around the world and admire how they look at the end, without knowing how it all began or what happens behind the scenes. It’s like a show,” says Anat Tocker, deputy CEO of NTA and head of the Green Line project. “A tremendous amount of work goes into making this happen.”

Construction began in 2018. The full opening of the Green Line in the Dan metropolitan area was originally planned for 2026 to 2027, but following significant delays, the southern segment, from Holon to Rishon LeZion, is now scheduled to open in 2028. The full line, extending north to Herzliya, is expected to begin operating in 2030.

“Even during the war, which was extremely complex and marked by labor shortages, we did not stop for a moment,” Tocker says. “Israeli industry supplied equipment and labor so the project could continue, despite a steel embargo, challenges in bringing in foreign workers, and complicated logistics.”

One of the highlights of the underground work has been tunnel excavation using a tunnel boring machine, or TBM, which operated around the clock with millimeter-level precision. “We excavated two tunnels as wide as a two-lane road, 24/7, with an international company and intensive Israeli involvement,” Tocker explains. Each section was excavated, reinforced with concrete elements and transported to designated disposal sites, eventually forming a tunnel system roughly five kilometers long. “Ultimately, the rail tracks will run here. We are already very close to the final platform level that we will all use in the future.”

Beyond the massive machines, cranes and trucks, dozens of foreign workers from China are at work at each site and station, manually placing every steel bar, one by one, with care and precision. At exactly noon, they break for rest, climbing the stairs and sometimes choosing to nap beside their tools instead of making the full ascent.

The light rail systems in the Tel Aviv area and in Jerusalem are also seen as preparation for the country’s largest transportation project now in its early stages: the Dan metro. That future network will require thousands of foreign workers and construction that is far more complex.

The vision of the Transportation Ministry for the crowded Dan metropolitan area is a fully integrated transit network, allowing passengers to move seamlessly between light rail lines, heavy rail and buses, without turning each journey into a grueling ordeal. “The Green Line will bring a major change to residents of the Tel Aviv area, both on its own and through its connections to the Purple Line and the future metro,” Tocker says.

The line passes through shopping areas, employment centers, Herzliya Pituah, Kiryat Atidim, the mall districts of Rishon LeZion, and city centers, including Tel Aviv and Holon. “It will serve people daily, for work, culture, leisure and studies,” she says.

One distinctive feature of the line is its seven bridges, which create grade separation and allow for higher speeds and operational efficiency. “The goal is to give people a real reason to leave their car at home and use mass transit daily, easing congestion for everyone,” Tocker adds.

The project recently moved from the “Infra One” phase to “Infra Two,” transitioning from heavy underground infrastructure work to the installation of systems and tracks, including rails, electrification, signaling and station systems. “This marks the shift from civil engineering preparation to the stage where trains will actually run,” Tocker explains.

There will be four underground stations in central Tel Aviv, including the one beneath Rabin Square, and another at Carlebach station, where the Green Line will connect with the Red Line, enabling more efficient mass transit in the future.

The Green Line will stretch about 39 kilometers, roughly four kilometers of which will be underground. Dozens of stations will be built along the route, with an average distance of about 500 meters between above-ground stations and about 800 meters between underground stations. In total, four underground stations are planned, alongside a complex system of bridges and underpasses designed to enable safe crossings of major traffic arteries and integrate the rail line into the existing urban fabric.

Two depot complexes will also be built, in Holon and Herzliya, serving as maintenance and operations hubs, the operational heart of the light rail system.

According to project data, the line is expected to serve about 250,000 passengers per day, and in the long term reach about 80 million passengers annually, figures that illustrate the scale of the project and its transportation potential.

Because of the line’s length and the extended construction period, the Transportation Ministry instructed the project company about a year ago to enable partial early operation, so the public would not have to wait until the final segment is completed to benefit. As a result, two opening stages were set: in 2028, the southern segment between Tel Aviv and Lewinsky, where the Green Line will connect to the Purple Line, also scheduled to open that year; and in 2030, the full opening to the northern terminus in Herzliya.

The entire system is designed to operate at high frequency, with a train every four minutes during peak hours, a level of service that sets an advanced standard compared to current public transportation in the Tel Aviv area. The approved construction budget stands at about 17.2 billion shekels, reflecting not only the project’s scale but also the responsibility to meet timelines and maintain execution quality.

Today, dozens of sections are already under construction, some fully completed and others having finished their initial work phases. In several locations, the first tracks have already been laid. At the same time, NTA is working to restore streets to routine use in areas where major stages have been completed, focusing on underground station work and completing lifts at the Ayalon Bridge, one of the project’s most complex engineering sites.

The central challenge is integrating a national-scale project into a dense, active and sensitive urban environment. Every excavation, road closure or traffic change has an immediate impact on residents, businesses and drivers. Around 40 additional road closures are still expected at intersections along the route, and residents’ patience will continue to be tested in the coming years.

Tocker is fully aware of the difficulty. “We understand the complexity and the patience it requires,” she says. “We are working closely with municipalities to ease things wherever possible. About 250,000 passengers a day will use the Green Line. We are talking about tens of millions of trips a year. There is something to wait for.”